Not Thou But I

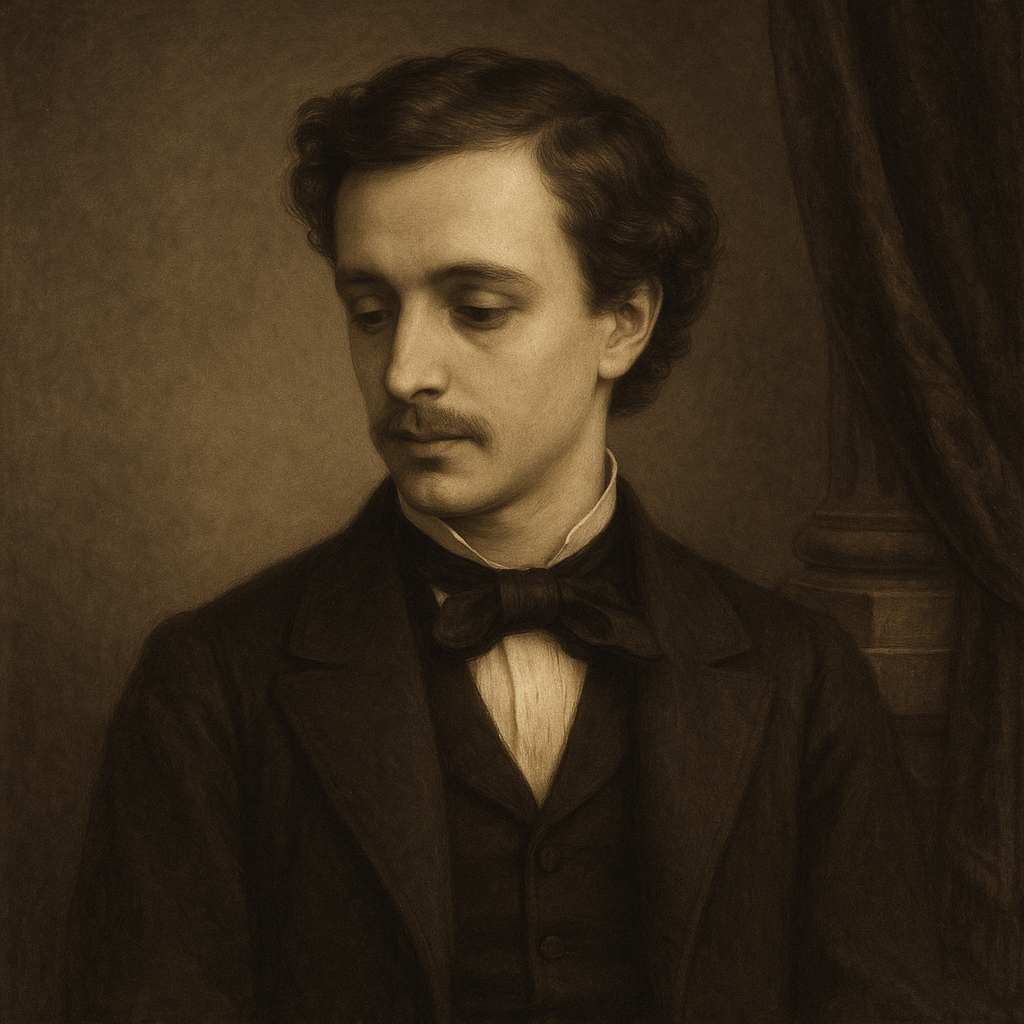

Philip Bourke Marston

1850 to 1887

It must have been for one of us, my own,

To drink this cup and eat this bitter bread.

Had not my tears upon thy face been shed,

Thy tears had dropped on mine; if I alone

Did not walk now, thy spirit would have known

My loneliness; and did my feet not tread

This weary path and steep, thy feet had bled

For mine, and thy mouth had for mine made moan:

And so it comforts me, yea, not in vain.

To think of thine eternity of sleep;

To know thine eyes are tearless though mine weep:

And when this cup's last bitterness I drain,

One thought shall still its primal sweetness keep, —

Thou hadst the peace and I the undying pain.

Philip Bourke Marston's Not Thou But I

Philip Bourke Marston’s "Not Thou But I" is a poignant elegy that explores grief, sacrifice, and the paradoxical comfort found in a loved one’s absence. Written in the Victorian era—a period marked by both intense emotional repression and profound meditations on mortality—the poem stands as a testament to the complexities of mourning. Through its intricate interplay of imagery, contrast, and emotional depth, Marston crafts a work that transcends mere personal lamentation, touching upon universal themes of love, loss, and endurance.

This essay will examine the poem through multiple lenses: its historical and cultural context, its literary devices, its thematic preoccupations, and its emotional resonance. Additionally, we will consider Marston’s personal tragedies, which deeply informed his writing, and explore how "Not Thou But I" fits within the broader tradition of elegiac poetry.

Historical and Cultural Context: Victorian Mourning and the Elegiac Tradition

The Victorian era was characterized by an intense preoccupation with death and mourning, influenced by high mortality rates due to disease, childbirth complications, and war. The cultural rituals surrounding death—elaborate funerals, mourning attire, posthumous portraiture—reflected a society deeply engaged with grief. Poetry, too, became a medium for processing loss, with elegies serving as both personal catharsis and public meditation on mortality.

Marston, born in 1850, was no stranger to tragedy. Blinded in infancy due to a medical error, he later endured the successive deaths of nearly all his loved ones—his fiancée, his closest friends (including Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sister, Christina Rossetti, who was a significant influence), and his siblings. This relentless accumulation of loss imbued his poetry with a haunting authenticity. "Not Thou But I" is not merely an abstract reflection on death but a visceral articulation of lived sorrow.

The poem aligns with the Victorian elegiac tradition, yet it distinguishes itself through its inversion of conventional consolation. Unlike Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which moves toward tentative hope, or Christina Rossetti’s "Remember," which offers a gentle resignation, Marston’s poem fixates on the speaker’s solitary suffering as a form of twisted relief—his pain is preferable to the beloved’s.

Literary Devices: Imagery, Paradox, and Syntactical Mastery

Marston employs a range of literary devices to convey the depth of his grief, with imagery and paradox being the most striking.

1. Sacrificial Imagery

The poem opens with a metaphor of shared suffering:

"It must have been for one of us, my own, / To drink this cup and eat this bitter bread."

The "cup" and "bitter bread" evoke Eucharistic symbolism, suggesting a communion of sorrow. Yet unlike the Christian sacrament, which promises redemption, this ritual offers only the bleak comfort of having endured instead of the beloved. The imagery is visceral—bitterness, tears, bleeding feet—reinforcing the physicality of grief.

2. Paradox and Consolation Through Pain

The central paradox of the poem lies in the speaker’s assertion that his suffering is preferable to the beloved’s:

"And so it comforts me, yea, not in vain, / To think of thine eternity of sleep."

This is not the conventional solace of reunion in an afterlife but a grim acknowledgment that the beloved is spared further pain. The speaker’s tears are a testament to his survival, while the dead lover’s "tearless" eyes signify an end to suffering. The final lines crystallize this paradox:

"Thou hadst the peace and I the undying pain."

Here, "peace" and "undying pain" are inextricably linked—one cannot exist without the other. This duality reflects the Victorian tension between the desire for eternal rest and the agony of those left behind.

3. Syntactical Control and Emotional Intensity

Marston’s use of enjambment and caesurae creates a rhythm that mirrors the ebb and flow of grief. The lines:

"Had not my tears upon thy face been shed, / Thy tears had dropped on mine"

carry a breathless urgency, the lack of pauses reinforcing the inevitability of shared sorrow. The conditional phrasing ("Had not... Thy tears had...") suggests an alternate reality where roles are reversed, deepening the sense of inescapable fate.

Themes: Love as Sacrifice, the Burden of Survival

At its core, "Not Thou But I" is a meditation on love’s sacrificial nature. The speaker does not merely mourn; he actively chooses to bear suffering so that the beloved does not have to. This theme aligns with Victorian ideals of self-abnegation, particularly in the context of romantic and familial devotion.

1. The Survivor’s Guilt and Solitude

The poem’s middle lines emphasize isolation:

"Did not walk now, thy spirit would have known / My loneliness."

The speaker’s "weary path and steep" is both literal and metaphorical—a pilgrimage through grief that the beloved has been spared. This evokes the classical tradition of the via dolorosa, but here, the journey is solitary, devoid of divine purpose.

2. The Permanence of Pain vs. the Tranquility of Death

Marston subverts the traditional elegy’s movement toward consolation. Instead of finding peace in memory, the speaker clings to pain as proof of love:

"One thought shall still its primal sweetness keep."

The "sweetness" is not joy but the grim satisfaction of having endured. This aligns with Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophical assertion that suffering is intrinsic to existence—those who live must bear it, while death offers the only true reprieve.

Comparative Analysis: Marston and His Contemporaries

Marston’s work invites comparison with other Victorian poets of grief:

-

Tennyson’s In Memoriam grapples with doubt and eventual reconciliation, whereas Marston offers no such resolution.

-

Christina Rossetti’s "Remember" gently instructs the beloved to forget if it eases pain, while Marston’s speaker insists on the necessity of his own suffering.

-

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s "Grief" portrays raw anguish, but Marston’s poem is more controlled, its despair measured in careful paradoxes.

Unlike these poets, Marston does not seek transcendence. His consolation is purely negative—the beloved’s escape from pain—which makes his elegy uniquely stark.

Emotional Impact: The Reader’s Experience

The poem’s power lies in its unflinching honesty. There is no sentimentalizing of death, no false comfort. The reader is left with the unsettling realization that love and grief are intertwined—that to love deeply is to accept the inevitability of suffering.

The final line—"Thou hadst the peace and I the undying pain"—resonates because it acknowledges what many elegies avoid: that mourning does not end. The "undying" nature of the speaker’s pain suggests an eternity of remembrance, a burden willingly carried.

Conclusion: A Testament to Enduring Love

"Not Thou But I" is a masterpiece of elegiac poetry, distinguished by its emotional precision and lack of sentimental evasion. Marston’s personal tragedies suffuse the poem with authenticity, while his skillful use of paradox and imagery elevates it beyond mere personal lament.

In a culture that often sanitized death, Marston’s unrelenting focus on pain as the price of love was radical. His poem does not offer solace in the conventional sense but provides something perhaps more profound: a recognition that true love means bearing sorrow so another need not. In this way, "Not Thou But I" stands as one of the most moving and unsentimental elegies of the Victorian age—a stark, beautiful ode to the endurance of the grieving heart.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!