To Live Merrily

Robert Herrick

1591 to 1674

Now is the time for mirth;

Nor cheek or tongue be dumb;

For with th' flowery earth

The golden pomp is come.

The golden pomp is come;

For now each tree does wear,

Made of her pap and gum,

Rich beads of amber here.

Now reigns the Rose, and now

Th' Arabian dew besmears

My uncontrolled brow,

And my retorted hairs.

Homer, this health to thee!

In sack of such a kind,

That it would make thee see,

Though thou wert ne'er so blind

Next, Virgil I'll call forth,

To pledge this second health

In wine, whose each cup's worth

An Indian commonwealth.

A goblet next I'll drink

To Ovid; and suppose

Made he the pledge, he'd think

The world had all one nose.

Then this immensive cup

Of aromatic wine,

Catullus! I quaff up

To that terse muse of thine.

Wild I am now with heat:

O Bacchus! cool thy rays;

Or frantic I shall eat

Thy Thyrse, and bite the Bays!

Round, round, the roof does run;

And being ravish'd thus,

Come, I will drink a tun

To my Propertius.

Now, to Tibullus next,

This flood I drink to thee;

—But stay, I see a text,

That this presents to me.

Behold! Tibullus lies

Here burnt, whose small return

Of ashes scarce suffice

To fill a little urn.

Trust to good verses then;

They only will aspire,

When pyramids, as men,

Are lost i' th' funeral fire.

And when all bodies meet

In Lethe to be drown'd;

Then only numbers sweet

With endless life are crown'd.

Robert Herrick's To Live Merrily

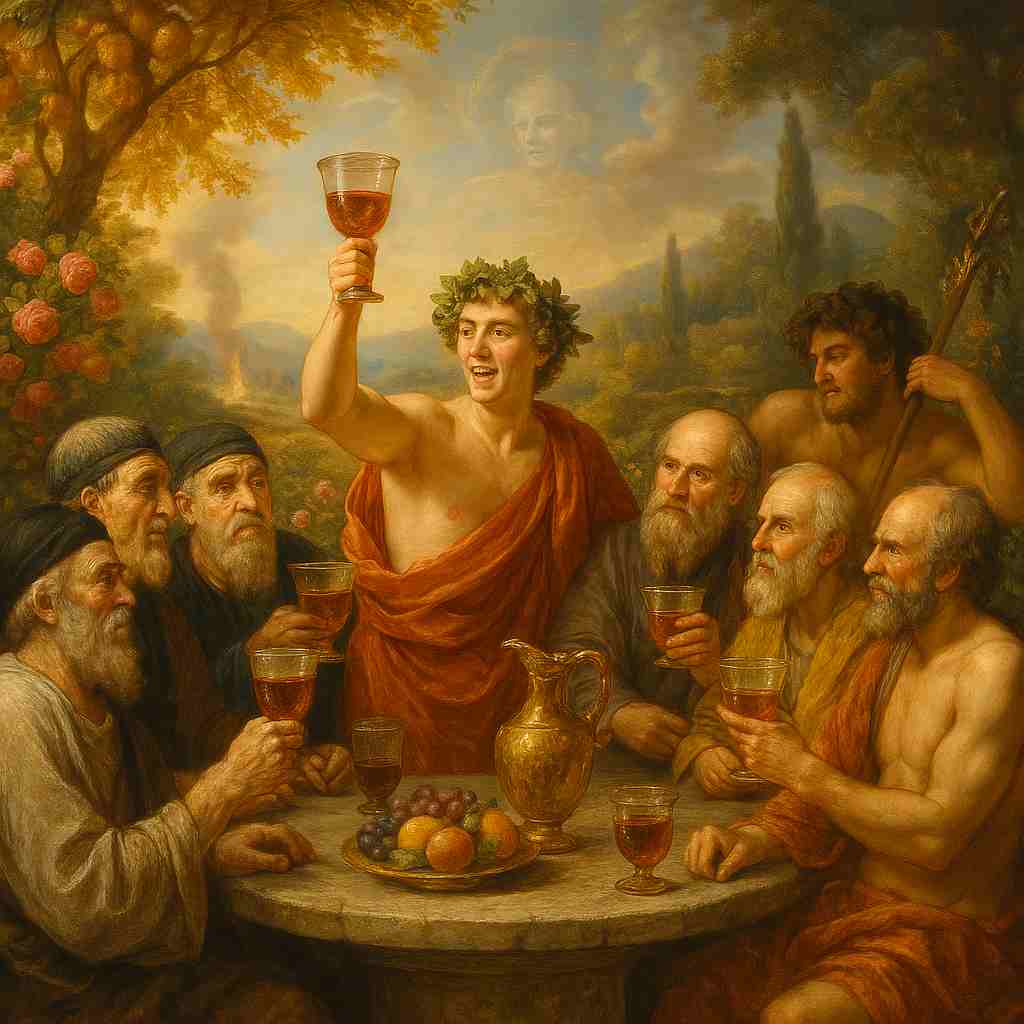

Robert Herrick’s To Live Merrily is a jubilant yet philosophically layered carpe diem poem that celebrates life, literature, and the fleeting nature of human existence. Written in the 17th century, the poem exemplifies the Cavalier poets’ embrace of pleasure, wit, and classical allusion, while also engaging with deeper meditations on mortality and artistic immortality. Through its vivid imagery, invocation of ancient poets, and playful yet profound tone, Herrick crafts a work that is both an exhortation to joy and a meditation on the enduring power of poetry.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider Herrick’s biographical influences, the poem’s philosophical underpinnings, and its place within the broader tradition of carpe diem poetry.

Historical and Cultural Context

The Cavalier Poets and the Caroline Era

Herrick was a prominent figure among the Cavalier poets, a group of 17th-century writers who flourished under the reign of Charles I. These poets, including Thomas Carew, Richard Lovelace, and Sir John Suckling, were known for their lyrical elegance, classical allusions, and themes of love, wine, and the transience of life. Unlike the Metaphysical poets (such as John Donne), who favored complex conceits and intellectual depth, the Cavaliers embraced a more refined, hedonistic, and often urbane aesthetic.

To Live Merrily reflects the Cavalier spirit in its celebration of sensory pleasures—wine, nature, and poetry—while also acknowledging the inevitability of death. The poem’s convivial tone aligns with the aristocratic culture of the time, where feasting, drinking, and literary patronage were central to courtly life.

Classical Influences and the Carpe Diem Tradition

Herrick’s poem is deeply rooted in classical traditions, particularly the carpe diem (“seize the day”) motif popularized by Horace and later by Renaissance poets. The invocation of Homer, Virgil, Ovid, Catullus, Propertius, and Tibullus situates Herrick within a lineage of poets who sought to reconcile earthly pleasures with the certainty of death.

The poem’s structure—moving from exuberant celebration to sober reflection—mirrors the Horatian ode, which often balances mirth with philosophical gravity. Herrick’s playful yet reverential tone toward these ancient poets suggests a self-conscious awareness of his own place in literary history.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Sensory and Natural Imagery

Herrick employs lush, sensory imagery to evoke the vibrancy of life. The opening stanzas depict nature in full bloom:

"For with th’ flowery earth / The golden pomp is come."

The “golden pomp” suggests both the opulence of nature and the fleeting splendor of youth and vitality. The image of trees adorned with “rich beads of amber” (likely referring to sap or blossoms) reinforces this theme of natural abundance.

Mythological and Literary Allusions

The poem’s middle stanzas are a series of toasts to classical poets, each framed with playful exaggeration. Herrick’s choice of poets is significant:

-

Homer and Virgil represent epic grandeur and enduring literary legacy.

-

Ovid, associated with metamorphosis and wit, is humorously imagined approving of the drinking (“he’d think / The world had all one nose”).

-

Catullus, known for his passionate and terse verse, is honored with an “immensive cup” of wine.

-

Propertius and Tibullus, both Roman elegists, serve as reminders of love and loss.

These allusions elevate the poem from mere revelry to a dialogue with literary tradition, suggesting that poetry itself is a form of immortality.

Juxtaposition of Life and Death

The poem’s tone shifts dramatically in the final stanzas with the mention of Tibullus’s death:

"Behold! Tibullus lies / Here burnt, whose small return / Of ashes scarce suffice / To fill a little urn."

This sudden intrusion of mortality starkly contrasts with the earlier exuberance, reinforcing the carpe diem theme. The image of ashes in an urn recalls the memento mori tradition, reminding readers that even great poets are subject to decay.

Metaphor and Symbolism

The poem’s central metaphor—wine as a conduit of poetic inspiration—links Bacchic ecstasy with artistic creation. Herrick’s plea to Bacchus (“cool thy rays; / Or frantic I shall eat / Thy Thyrse, and bite the Bays!”) suggests the fine line between creative frenzy and self-destruction. The “Bays” (laurel leaves, symbolizing poetic achievement) imply that even in excess, the poet seeks glory.

Themes

The Transience of Life and the Power of Poetry

The poem’s most profound theme is the tension between ephemeral pleasures and eternal art. While the body decays (“when all bodies meet / In Lethe to be drown’d”), poetry endures:

"Then only numbers sweet / With endless life are crown’d."

Herrick suggests that while human life is fleeting, great verse transcends time, much like the works of the poets he toasts.

Hedonism with a Purpose

Unlike mere frivolity, Herrick’s celebration of wine and mirth is philosophically charged. The act of drinking becomes a ritual of communion with the past, linking the poet to his literary forebears. The poem thus advocates not just indulgence, but a mindful appreciation of life’s joys in the face of mortality.

The Poet’s Role in Immortality

By invoking classical poets, Herrick aligns himself with their legacy, implying that his own verses may one day be similarly honored. The closing lines assert poetry’s superiority over material monuments (“pyramids”), reinforcing the Renaissance belief in art’s enduring power.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Resonance

The poem’s emotional trajectory—from exuberance to contemplation—creates a poignant effect. The early stanzas intoxicate the reader with their vitality, while the later turn toward mortality invites sober reflection. This duality captures the essence of the human condition: the simultaneous desire for joy and the awareness of impermanence.

Philosophically, the poem engages with Epicurean and Stoic ideas. The call to “live merrily” echoes Epicurus’s advocacy of pleasure as life’s proper aim, while the acceptance of death reflects Stoic resolve. Herrick’s synthesis of these traditions suggests that true wisdom lies in embracing both joy and mortality.

Comparative Analysis

Herrick’s poem shares thematic and stylistic similarities with other carpe diem works:

-

Horace’s Odes (particularly *1.11*: “Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero”) advocate seizing the day but with a measured tone, whereas Herrick’s approach is more exuberant.

-

Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress employs a more urgent, seductive tone, but like Herrick, it contrasts life’s brevity with the persistence of art.

-

Ben Jonson’s Come, My Celia (from Volpone) similarly blends classical allusion with a celebration of pleasure.

Herrick’s unique contribution lies in his fusion of conviviality and literary homage, making To Live Merrily both a drinking song and a meditation on poetic immortality.

Biographical Insights

Herrick’s life as a clergyman (he was an Anglican vicar) adds an intriguing layer to his hedonistic verses. While some critics see a contradiction between his religious role and his libertine poetry, others argue that his work reflects a broader Renaissance humanism that reconciled piety with earthly pleasures. To Live Merrily may thus be read not as a rejection of spirituality, but as a celebration of God’s creation—both in nature and in human artistry.

Conclusion

To Live Merrily is a masterful synthesis of joy and wisdom, classical tradition and personal expression. Through its rich imagery, playful allusions, and profound thematic depth, Herrick crafts a poem that is both a call to revelry and a testament to poetry’s enduring power. The poem’s emotional resonance lies in its ability to evoke both the ecstasy of life and the solemnity of death, leaving the reader with a heightened appreciation for the fleeting yet precious nature of existence.

In the end, Herrick’s message is clear: live fully, drink deeply, and trust in the immortality of verse. Few poems capture the spirit of carpe diem with such infectious vitality and intellectual grace.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!