Quiet Work

Matthew Arnold

1822 to 1888

One lesson, Nature, let me learn of thee,

One lesson which in every wind is blown,

One lesson of two duties kept at one

Though the loud world proclaim their enmity—

Of toil unsever'd from tranquility!

Of labor, that in lasting fruit outgrows

Far noisier schemes, accomplish'd in repose,

Too great for haste, too high for rivalry.

Yes, while on earth a thousand discords ring,

Man's fitful uproar mingling with his toil,

Still do thy sleepless ministers move on,

Their glorious tasks in silence perfecting;

Still working, blaming still our vain turmoil,

Laborers that shall not fail, when man is gone.

Matthew Arnold's Quiet Work

Introduction

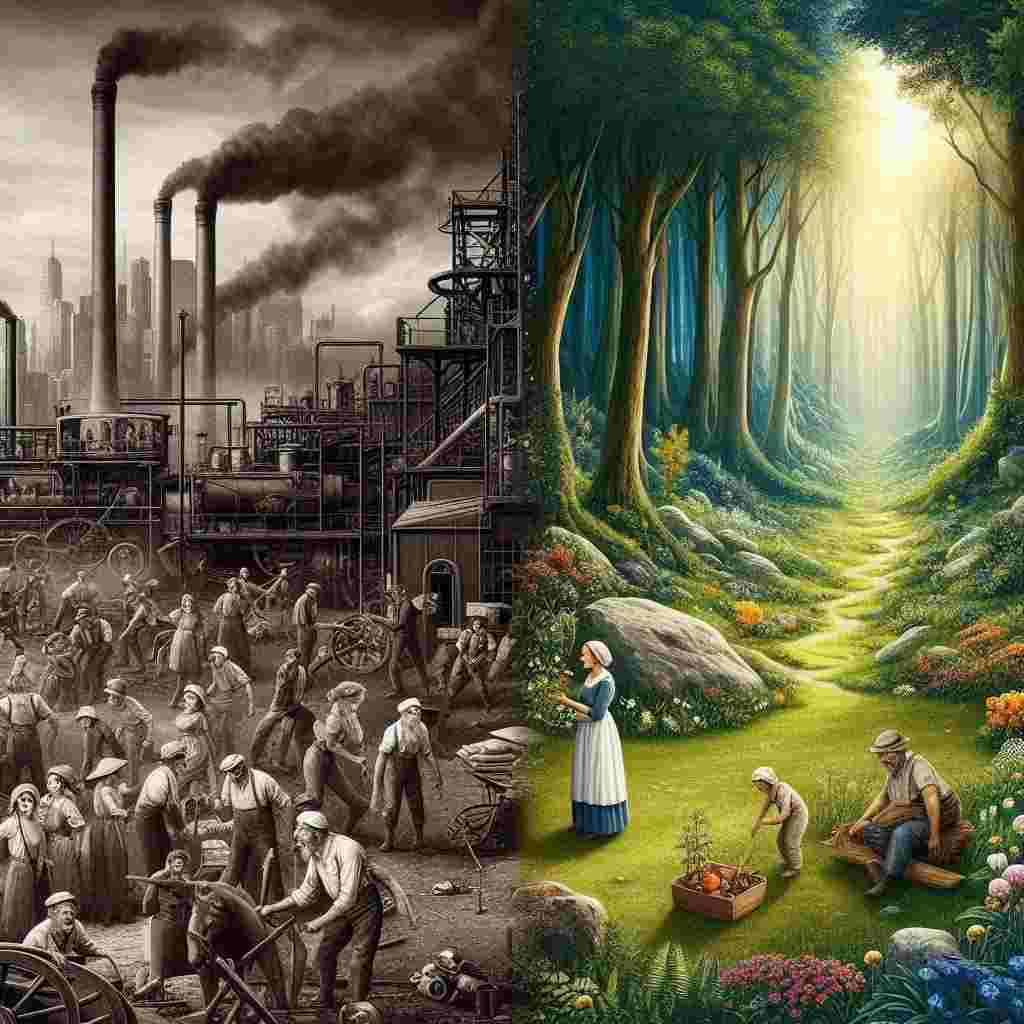

Matthew Arnold's sonnet "Quiet Work" stands as a testament to the poet's profound contemplation of nature's enduring wisdom and its stark contrast to human endeavors. This piece, nestled within Arnold's broader corpus of work, exemplifies his characteristic blend of philosophical inquiry and poetic craftsmanship. Through a meticulous examination of form, imagery, and thematic resonance, we can unravel the intricate tapestry of meaning woven into this compact yet profound piece of Victorian poetry.

Historical and Literary Context

To fully appreciate "Quiet Work," one must first situate it within the broader context of Arnold's oeuvre and the Victorian literary landscape. Composed during a period of rapid industrialization and social upheaval, the poem reflects the era's underlying anxieties about progress, purpose, and the human condition. Arnold, known for his critical stance on modern society's spiritual and intellectual deficiencies, employs nature as a counterpoint to human folly—a recurring theme in his work.

The sonnet form, with its rich tradition in English poetry, serves as an apt vessel for Arnold's meditative reflections. Its structured yet flexible framework allows for a nuanced exploration of the tension between human activity and natural processes, mirroring the very duality the poem seeks to elucidate.

Form and Structure

"Quiet Work" adheres to the Petrarchan sonnet structure, consisting of an octave (the first eight lines) followed by a sestet (the final six lines). This form traditionally introduces a problem or question in the octave and provides a resolution or reflection in the sestet. Arnold's masterful manipulation of this structure underscores the poem's thematic divide between human and natural realms.

The rhyme scheme (ABBAABBA CDCDCD) reinforces the poem's internal logic, with the tightly knit octave giving way to a more open-ended sestet. This transition mirrors the shift from the speaker's initial observation to a broader contemplation of nature's "sleepless ministers."

Imagery and Diction

Arnold's choice of imagery is both evocative and precise. The recurring motif of sound—"every wind," "loud world," "discords ring," "fitful uproar"—stands in stark contrast to the implicit silence of nature's work. This juxtaposition is further emphasized by the tactile imagery of "toil" and "labor," which connotes physical effort yet is paradoxically linked to "tranquility" and "repose."

The diction throughout the poem is carefully calibrated to reinforce its central thesis. Words like "unsever'd," "outgrows," and "accomplish'd" suggest a process of organic, unhurried development. This lexical field stands in opposition to terms like "haste" and "rivalry," which characterize human endeavors.

Thematic Analysis

At its core, "Quiet Work" presents a meditation on the dichotomy between human activity and the subtle, enduring processes of nature. The poem posits that nature offers a crucial lesson—one of harmonizing seemingly contradictory states: "toil unsever'd from tranquility" and "labor... accomplish'd in repose."

This paradoxical unity of effort and calm serves as a critique of human society's frenetic pace and competitive ethos. Arnold suggests that true accomplishment—"lasting fruit"—emerges not from "noisier schemes" but from patient, steady work that is "Too great for haste, too high for rivalry."

The sestet expands this individual lesson to a universal scale. The image of "a thousand discords ring" evokes the cacophony of human civilization, characterized by "fitful uproar" and "vain turmoil." In contrast, nature's "sleepless ministers" operate in silence, "perfecting" their "glorious tasks" without fanfare or recognition.

Philosophical Underpinnings

Arnold's poem can be read as an engagement with several philosophical traditions. The notion of learning from nature echoes Romantic ideals, particularly Wordsworth's concept of nature as a moral teacher. However, Arnold's approach is more measured, focusing on nature's processes rather than its sublime aspects.

The poem also resonates with Stoic philosophy, particularly in its emphasis on steady, purposeful work and the rejection of external validation. The idea that true achievement is "Too great for haste, too high for rivalry" aligns with Stoic notions of virtue and self-sufficiency.

Furthermore, the poem touches on existential themes. The final line, "Laborers that shall not fail, when man is gone," hints at the transience of human existence compared to the eternal processes of nature. This memento mori adds a layer of urgency to the poem's central lesson, suggesting that aligning oneself with nature's rhythms is not merely a path to productivity but a means of transcending mortality through meaningful work.

Literary Techniques

Arnold employs several literary devices to reinforce his message. The use of personification in describing nature's "sleepless ministers" imbues the natural world with a sense of purpose and agency. This anthropomorphism serves to elevate nature's processes to a level of conscious, deliberate action, further emphasizing the contrast with human "fitful uproar."

Alliteration and assonance feature prominently, creating a musical quality that underscores the poem's themes. For instance, the repetition of 'l' sounds in "lesson," "labor," "lasting," and "laborers" creates a sense of continuity and persistence, mirroring the steady work of nature.

The poem's central conceit—nature as a teacher—is sustained throughout, creating a cohesive metaphorical framework within which Arnold explores complex ideas about work, purpose, and human nature.

Comparative Analysis

"Quiet Work" invites comparison with other poems in Arnold's oeuvre, particularly those that deal with nature and human society. "Dover Beach," for instance, shares a similar contemplative tone and uses natural imagery to comment on the human condition. However, where "Dover Beach" expresses a sense of melancholy and loss, "Quiet Work" offers a more constructive, albeit challenging, vision.

In the broader context of Victorian poetry, Arnold's piece can be contrasted with the work of his contemporaries. Unlike Tennyson's often more ornate and mythologically rich nature poetry, or Browning's dramatic monologues exploring human psychology, Arnold's approach in "Quiet Work" is more directly didactic, presenting nature as a model for human behavior.

Conclusion

Matthew Arnold's "Quiet Work" emerges as a multifaceted exploration of the relationship between human endeavor and natural processes. Through its carefully constructed form, evocative imagery, and philosophical depth, the poem offers a critique of modern society's values while simultaneously presenting an alternative ethos derived from nature's example.

The enduring relevance of Arnold's message—the value of patient, purposeful work over frenetic activity and competition—speaks to the timeless quality of his poetic vision. In an age of increasing technological acceleration and social media-driven comparison, "Quiet Work" serves as a poignant reminder of the virtues of steady, unassuming labor and the wisdom inherent in nature's silent operations.

Ultimately, Arnold's sonnet transcends its Victorian origins, offering readers across time a moment of reflection on their own relationship to work, nature, and the broader rhythms of existence. It stands as a testament to poetry's power to distill complex philosophical ideas into a form that resonates both intellectually and emotionally, inviting us to reconsider our place in the natural world and the true meaning of productive, fulfilling labor.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!