Pastorale

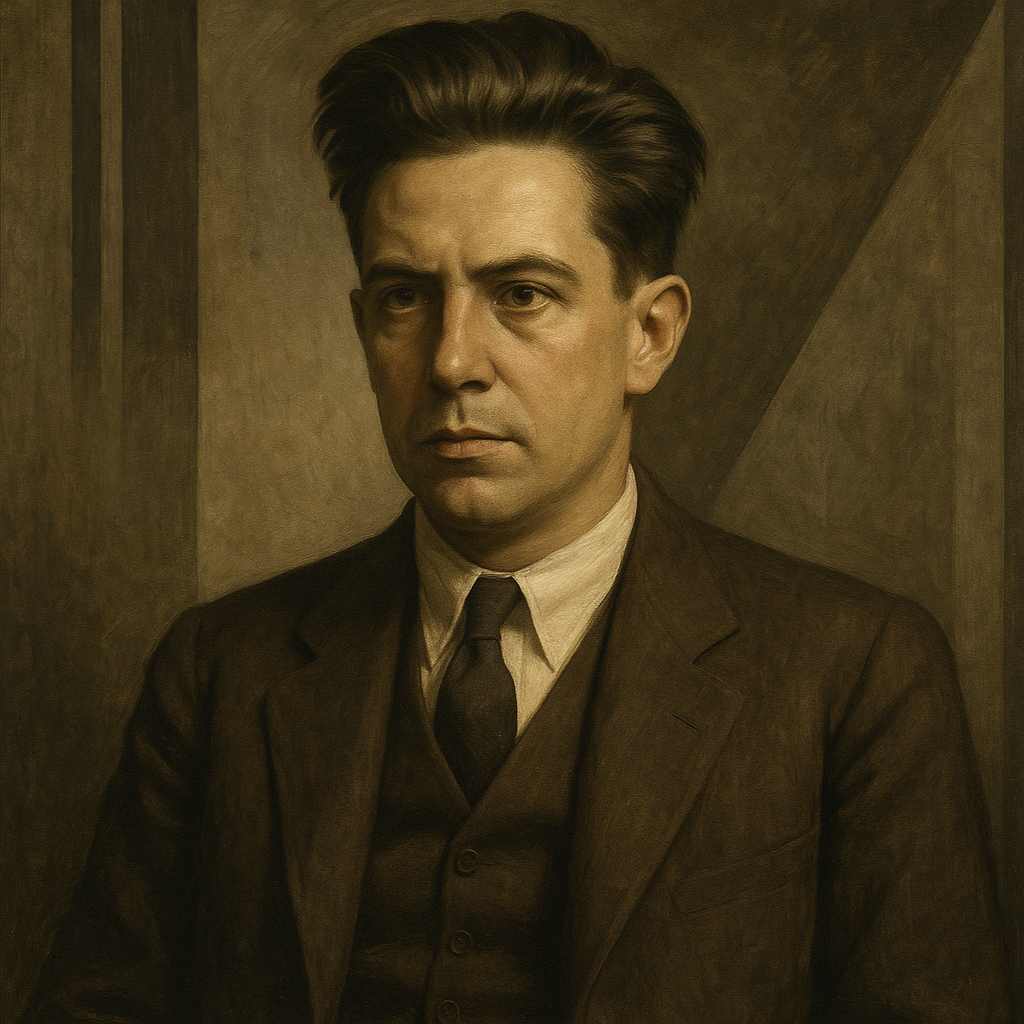

Hart Crane

1899 to 1932

No more violets,

And the year

Broken into smoky panels.

What woods remember now

Her calls, her enthusiasms.

That ritual of sap and leaves

The sun drew out,

Ends in this latter muffled

Bronze and brass. The wind

Takes rein.

If, dusty, I bear

An image beyond this

Already fallen harvest,

I can only query, "Fool—

Have you remembered too long;

Or was there too little said

For ease or resolution—

Summer scarcely begun

And violets,

A few picked, the rest dead?"

Hart Crane's Pastorale

Hart Crane’s Pastorale is a compact yet richly evocative poem that encapsulates themes of transience, memory, and the inevitable dissolution of beauty. Written during the early 20th century—a period marked by rapid industrialization, the aftermath of World War I, and shifting cultural paradigms—the poem subtly engages with the tension between nature and modernity, between pastoral idealism and the encroaching mechanized world. Through its vivid imagery, fragmented structure, and melancholic tone, Pastorale interrogates the fleeting nature of time and the inadequacy of human attempts to preserve it.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance. Additionally, we will consider Crane’s broader poetic project, his biographical influences, and possible philosophical underpinnings that inform the work.

Historical and Cultural Context

Hart Crane (1899–1932) was a major American poet whose work bridged the Romantic tradition and modernist experimentation. Writing in the 1920s and early 1930s, Crane was deeply influenced by the disillusionment of the post-war era, the rise of urbanization, and the fading of agrarian life. Pastorale (published in White Buildings, 1926) reflects these concerns, presenting a world where nature’s cyclical beauty is interrupted, leaving behind only fragments of what once was.

The title itself, Pastorale, evokes the pastoral tradition—a literary mode that idealizes rural life and nature’s harmony. However, Crane subverts this tradition by depicting a fractured landscape: “the year / Broken into smoky panels.” The poem’s setting is not one of bucolic serenity but of disintegration, suggesting the intrusion of industrialization (the “smoky panels” evoking factory pollution or the fragmented perception of modern life). This aligns with early 20th-century anxieties about the loss of natural beauty in the face of technological progress.

Crane’s work often engages with the American mythos, particularly the tension between the promise of the New World and its failures. In Pastorale, this manifests as a lament for lost innocence—violets that no longer bloom, a summer “scarcely begun” before it fades. The poem can thus be read as an elegy not just for a personal memory but for an entire cultural moment where the pastoral ideal has been irrevocably altered.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Crane’s poetry is renowned for its dense, allusive imagery, and Pastorale is no exception. The poem’s brevity belies its complexity, as each line is meticulously crafted to evoke sensory and emotional responses.

1. Fragmentation and Disintegration

The poem’s structure mirrors its thematic concern with decay. The opening lines—“No more violets, / And the year / Broken into smoky panels”—immediately establish a sense of rupture. The year is not merely passing but broken, its continuity disrupted. The “smoky panels” suggest both literal pollution and a fractured perception of time, as if the speaker can no longer see the year as a cohesive whole but only in disjointed glimpses.

This fragmentation extends to the natural world: “What woods remember now / Her calls, her enthusiasms.” The woods, traditionally a symbol of timeless nature, are reduced to a fading memory. The use of “her” introduces an ambiguous feminine presence—perhaps a lost lover, a muse, or even nature personified—whose vitality is now only a ghostly echo.

2. Metallurgical and Natural Imagery

Crane contrasts organic and industrial imagery to underscore the poem’s tension between nature and decay. The “ritual of sap and leaves”—a phrase evoking the natural cycles of growth—is juxtaposed with “this latter muffled / Bronze and brass.” These metallic terms suggest both autumnal decay (the browning of leaves) and the artificial, as if nature itself has been overtaken by something harsher, less alive.

The wind, traditionally a symbol of change or spirit, “takes rein,” implying an uncontrolled force driving the dissolution forward. Unlike the gentle breezes of pastoral poetry, this wind is an agent of erasure, hastening the end of the natural cycle.

3. Rhetorical Questions and Self-Interrogation

The poem’s second half shifts to a more introspective tone, with the speaker questioning his own role in this dissolution:

“If, dusty, I bear

An image beyond this

Already fallen harvest,

I can only query, ‘Fool—

Have you remembered too long;”

The self-address (“Fool”) suggests a crisis of memory and perception. The speaker wonders whether his clinging to the past (“remembered too long”) is itself a kind of folly, or whether the failure lies in the insufficiency of expression (“was there too little said”). This introspective turn aligns with modernist concerns about the limitations of language and memory in capturing experience.

The final lines—“Summer scarcely begun / And violets, / A few picked, the rest dead?”—reinforce the theme of premature loss. The violets, symbols of fleeting beauty, are either plucked (preserved artificially) or already dead, leaving no middle ground between preservation and decay.

Themes

1. Transience and Impermanence

At its core, Pastorale is a meditation on ephemerality. The violets are gone, the year is fractured, and even the woods’ memory is fading. Unlike traditional pastorals, which often celebrate nature’s eternal return, Crane’s poem suggests an irrevocable rupture. The “fallen harvest” implies not just seasonal decay but a finality, as if the cycles of renewal have been disrupted.

2. The Failure of Memory and Language

The speaker’s self-doubt (“Have you remembered too long”) raises questions about the reliability of memory. Is nostalgia a form of delusion? Similarly, the line “was there too little said” hints at the inadequacy of language to encapsulate experience. This aligns with Crane’s broader poetic struggle—seen in works like The Bridge—to articulate transcendence in a fragmented world.

3. Nature vs. Industrialization

While not explicitly political, the poem’s imagery of smoke and metal subtly critiques industrialization’s impact on the natural world. The pastoral ideal is no longer sustainable; even the wind, a natural force, seems complicit in the erosion of beauty.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Underpinnings

Pastorale resonates with a quiet, haunting melancholy. Unlike grand elegies, its sorrow is understated, making its impact all the more piercing. The speaker’s lament is not just for lost violets but for an entire mode of being that can no longer be sustained.

Philosophically, the poem evokes Walter Benjamin’s idea of “homogeneous, empty time”—modernity’s disruption of natural and historical rhythms. The “broken” year and the “smoky panels” suggest a world where time is no longer cyclical but fractured, leaving the speaker grasping for meaning.

Comparative and Biographical Insights

Crane’s work often intersects with T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in its depiction of fragmentation and cultural decay. However, where Eliot’s tone is often detached and ironic, Crane’s is deeply personal, even vulnerable.

Biographically, Crane’s tumultuous life—marked by alcoholism, familial strife, and eventual suicide—infuses his poetry with a sense of longing and despair. Pastorale’s questioning of memory (“Have you remembered too long?”) may reflect Crane’s own struggles with the past and his search for artistic redemption.

Conclusion

Pastorale is a masterful distillation of Hart Crane’s poetic vision: lush yet austere, nostalgic yet acutely aware of modernity’s ravages. Through its fragmented imagery, introspective voice, and interplay of natural and industrial motifs, the poem captures a moment of transition—both personal and cultural—where beauty is fleeting, memory is unreliable, and the pastoral dream is no longer tenable.

In its brevity, Pastorale achieves a profound emotional depth, leaving the reader with the same quiet unease as its speaker: the sense that something vital has been lost, and that even language cannot fully recover it. It is a poem that lingers, like the faint echo of a call in the woods, long after the last line is read.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!