Religion

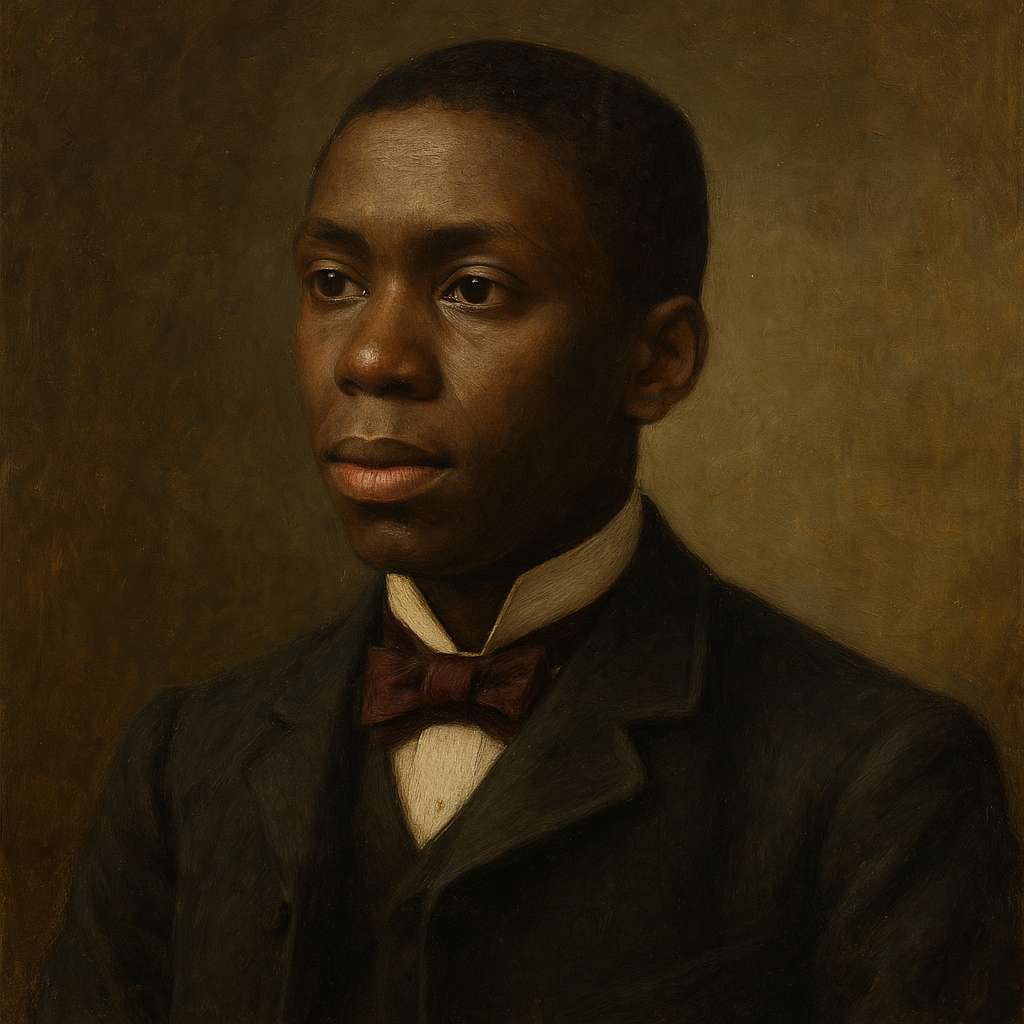

Paul Laurence Dunbar

1872 to 1906

I am no priest of crooks nor creeds,

For human wants and human needs

Are more to me than prophets' deeds;

And human tears and human cares

Affect me more than human prayers.

Go, cease your wail, lugubrious saint!

You fret high Heaven with your plaint.

Is this the "Christian's joy" you paint?

Is this the Christian's boasted bliss?

Avails your faith no more than this?

Take up your arms, come out with me,

Let Heav'n alone; humanity

Needs more and Heaven less from thee.

With pity for mankind look 'round;

Help them to rise—and Heaven is found.

Paul Laurence Dunbar's Religion

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “Religion” is a striking critique of organized religion’s failure to address human suffering. Written in the late 19th or early 20th century, the poem reflects Dunbar’s skepticism toward hollow religiosity that prioritizes doctrine over compassion. Through direct, impassioned language, Dunbar challenges the reader to reconsider the true essence of faith—not in ritualistic devotion, but in active empathy for humanity. This essay explores the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional resonance, while also considering Dunbar’s personal philosophy and broader philosophical perspectives on religion and morality.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate “Religion,” one must situate it within Dunbar’s lived experience as an African American in post-Reconstruction America. Born in 1872 to formerly enslaved parents, Dunbar witnessed the persistent racial injustices of the late 19th century—lynchings, segregation, and economic disenfranchisement—all occurring alongside the pervasive influence of the Black Church, which served as both a spiritual refuge and a political organizing space for African Americans.

However, Dunbar’s poem does not merely critique the Black Church; it questions institutionalized religion broadly, particularly its tendency toward passive piety rather than active justice. This aligns with broader intellectual currents of the time, including the rise of secular humanism and the Social Gospel movement, which emphasized Christianity’s role in social reform. Dunbar’s skepticism mirrors that of contemporaries like W.E.B. Du Bois, who, in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), critiqued the emotional excesses of Black religious expression while still recognizing its cultural significance.

Furthermore, Dunbar’s poem resonates with earlier transcendentalist critiques of organized religion, particularly those of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who in “The Divinity School Address” (1838) condemned a clergy more concerned with tradition than moral vitality. Dunbar’s assertion that “human wants and human needs / Are more to me than prophets’ deeds” echoes Emerson’s call for a religion rooted in personal moral intuition rather than institutional dogma.

Literary Devices and Structure

Dunbar employs several literary devices to underscore his critique, the most prominent being diction, rhetorical questioning, and imperative verbs.

1. Diction and Tone

The poem’s tone is confrontational and urgent, rejecting passive religiosity in favor of action. Words like “crooks,” “lugubrious,” and “plaint” carry negative connotations, painting religious figures as hypocritical or ineffectual. The speaker’s disdain for empty piety is evident in lines like:

“Go, cease your wail, lugubrious saint! / You fret high Heaven with your plaint.”

The term “lugubrious” (excessively mournful) suggests that the “saint’s” prayers are performative rather than transformative.

2. Rhetorical Questions

Dunbar uses rhetorical questions to challenge religious complacency:

“Is this the ‘Christian’s joy’ you paint? / Is this the Christian’s boasted bliss?”

These questions force the reader to confront the disparity between religious rhetoric and lived reality. If faith does not alleviate suffering, what good is it?

3. Imperative Verbs

The poem shifts from critique to a call to action, marked by commanding verbs:

“Take up your arms, come out with me… / Help them to rise—and Heaven is found.”

This imperative mood transforms the poem from a lament into a manifesto, urging the reader toward tangible change.

Themes

1. Critique of Performative Religion

Dunbar’s central argument is that religion, when divorced from action, becomes meaningless. The “priest of crooks nor creeds” symbolizes clergy who prioritize doctrine over human welfare. This aligns with biblical critiques of hypocritical religiosity, such as Jesus’ condemnation of the Pharisees in Matthew 23.

2. Humanism Over Dogma

The poem champions humanism—the belief that ethical action, not ritual, defines true spirituality. The lines:

“human tears and human cares / Affect me more than human prayers”

suggest that empathy, not prayer, is the highest moral duty. This reflects Enlightenment humanism as well as the Social Gospel’s emphasis on societal reform.

3. Heaven as Earthly Justice

The closing lines redefine Heaven not as a distant reward but as the result of earthly solidarity:

“Help them to rise—and Heaven is found.”

This mirrors Marxist and liberation theology perspectives, which view salvation as collective liberation rather than individual piety.

Emotional Impact

Dunbar’s poem is emotionally charged, blending frustration with hope. The opening stanzas convey exasperation at hollow religiosity, while the final lines offer a redemptive vision. The shift from critique to exhortation creates a sense of urgency, compelling the reader to move beyond passive faith into active compassion.

Comparative Analysis

Dunbar’s “Religion” can be compared to Langston Hughes’ “Goodbye Christ” (1932), which similarly critiques institutional Christianity’s failure to address oppression. Both poets reject passive religiosity, though Hughes’ poem is more explicitly radical, while Dunbar’s retains a moralistic tone.

Another parallel exists with Emily Dickinson’s “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church” (1864), which privileges personal spirituality over organized worship. However, Dunbar’s poem is more socially engaged, emphasizing communal action rather than individual contemplation.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Dunbar’s personal struggles—racial discrimination, illness, and professional frustrations—likely influenced his skepticism toward facile religiosity. His poem suggests that faith must be proven through deeds, not words.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with pragmatism (e.g., William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience), which evaluates religion based on its real-world effects. If prayer does not alleviate suffering, it is functionally useless—a sentiment Dunbar echoes.

Conclusion

“Religion” is a powerful indictment of empty piety and a call for faith rooted in action. Dunbar’s critique remains relevant today, as debates over the role of religion in social justice persist. By privileging human suffering over doctrinal adherence, Dunbar challenges readers to redefine spirituality as active compassion—making Heaven not a distant promise, but a present possibility.

In an era where performative allyship often replaces substantive change, Dunbar’s words resonate with renewed urgency: true religion is not in prayer alone, but in lifting others up.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!