Vestigia

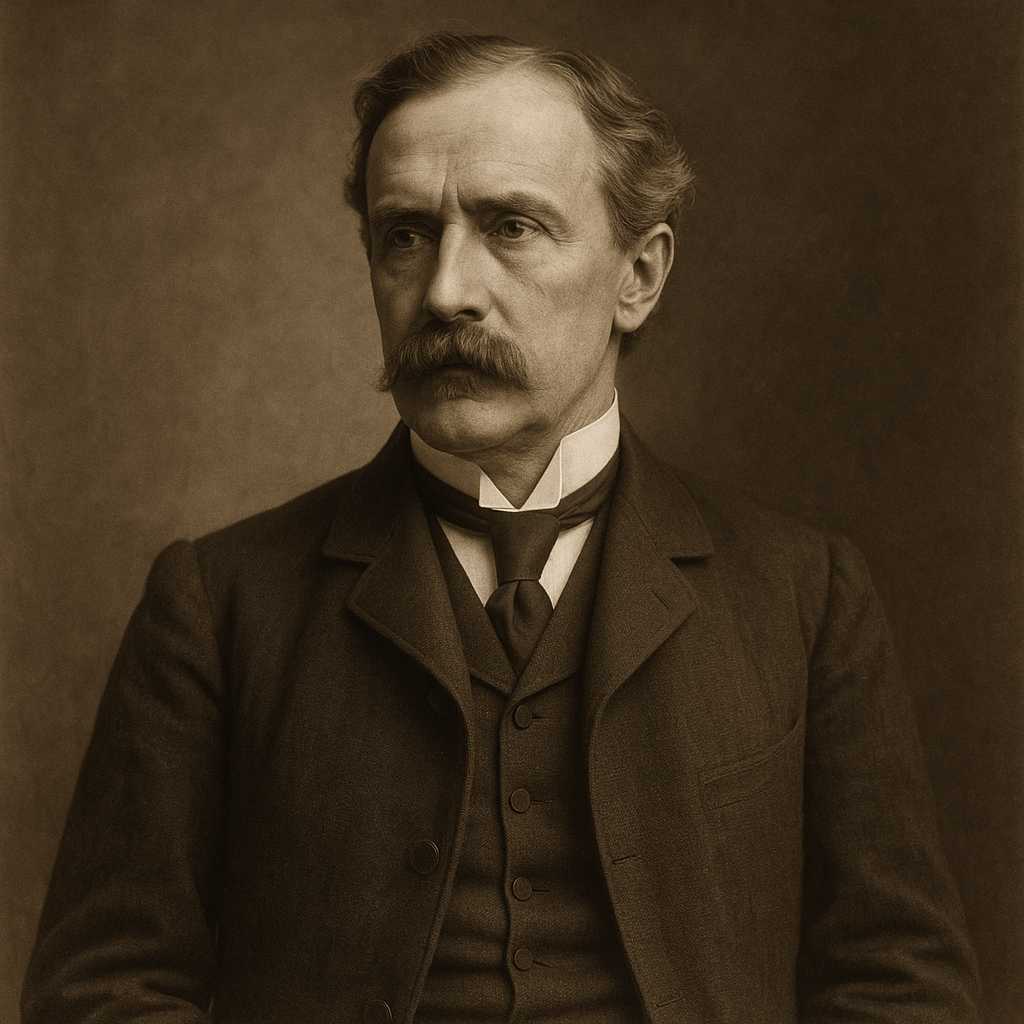

Bliss Carman

1861 to 1929

I took a day to search for god,

And found Him not. But as I trod

By rocky ledge, through woods untamed,

Just where one scarlet lily flamed,

I saw His footprint in the sod.

Then suddenly, all unaware,

Far off in the deep shadows, where

A solitary hermit thrush

Sang through the holy twilight hush—

I heard His voice upon the air.

And even as I marvelled how

God gives us Heaven here and now,

In a stir of wind that hardly shook

The poplar leaves beside the brook—

His hand was light upon my brow.

At last with evening as I turned

Homeward, and thought what I had learned

And all that there was still to probe—

I caught the glory of His robe

Where the last fires of sunset burned.

Back to the world with quickening start

I looked and longed for any part

In making saving Beauty be….

And from that kindling ecstasy

I knew God dwelt within my heart.

Bliss Carman's Vestigia

Bliss Carman’s Vestigia is a lyrical meditation on the divine presence in nature, framed as a spiritual quest that culminates in an epiphany of immanence rather than transcendence. The poem’s title, derived from the Latin for "footprints" or "traces," immediately signals its central concern: the search for God not in the abstract realms of theology but in the tangible, sensory world. Carman, a Canadian poet deeply influenced by the Romantic and Transcendentalist traditions, crafts a work that is both intimate and universal, blending personal revelation with a broader philosophical inquiry into the nature of the sacred.

This essay will explore Vestigia through multiple lenses: its historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its thematic preoccupations, and its emotional resonance. Additionally, we will consider how the poem aligns with and diverges from Carman’s broader oeuvre, as well as its affinities with the works of other nature mystics such as Wordsworth, Emerson, and Whitman.

Historical and Cultural Context

Bliss Carman (1861–1929) was a key figure in the Confederation Poets, a group of Canadian writers who sought to articulate a distinct national literary identity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work is deeply infused with the Romantic tradition, particularly the Wordsworthian reverence for nature as a locus of spiritual revelation. However, Carman also engaged with the Transcendentalist ideas of Emerson and Thoreau, who posited that the divine could be directly apprehended through the natural world without the mediation of institutional religion.

Vestigia was published in Carman’s 1893 collection Low Tide on Grand Pré, a volume that reflects his preoccupation with the interplay of nature, spirituality, and human emotion. The late Victorian period, in which Carman wrote, was marked by both religious doubt and a burgeoning interest in mysticism and pantheism. The poem’s gentle affirmation of divine presence—without dogmatic assertions—resonates with the era’s spiritual seeking, offering a solace that is personal rather than doctrinal.

Literary Devices and Structure

Though this analysis deliberately avoids discussion of rhyme scheme, Vestigia employs a range of other literary devices that contribute to its meditative power.

1. Imagery and Symbolism

Carman’s poem is rich in natural imagery, each element carefully chosen to suggest the divine without explicit declaration. The "scarlet lily" (line 4) is not merely a flower but a sudden, vivid sign of sacred presence, reminiscent of the burning bush in the Biblical story of Moses. Its flaming color suggests both beauty and revelation, a momentary glimpse of the eternal within the ephemeral.

Similarly, the "hermit thrush" (line 8) carries symbolic weight. In North American literary tradition, the hermit thrush is often associated with solitude and spiritual purity—most famously in Whitman’s When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, where it serves as a symbol of transcendent mourning. Carman’s thrush, singing in the "holy twilight hush," becomes a vessel for divine voice, reinforcing the idea that God speaks not in thunderous proclamations but in quiet, natural harmonies.

2. Sensory Language and Synesthesia

The poem engages multiple senses to evoke a holistic experience of the sacred. The visual ("scarlet lily," "last fires of sunset"), the auditory ("hermit thrush / Sang through the holy twilight hush"), and the tactile ("His hand was light upon my brow") work in concert to create a fully immersive moment of revelation. This multisensory approach reflects the Transcendentalist belief that spiritual truth is apprehended through direct, unmediated experience rather than through intellectual abstraction.

3. Paradox and Epiphany

The poem’s central paradox lies in its assertion that God is found not in the grand or the distant but in the immediate and the ordinary. The speaker begins by stating, "I took a day to search for god, / And found Him not" (lines 1–2), only to discover divine traces in the lily, the thrush’s song, the wind, and the sunset. This structure mirrors the Romantic and Transcendentalist trope of the "momentary glimpse," where the infinite is revealed in fleeting instants.

The final stanza’s declaration—"I knew God dwelt within my heart" (line 20)—resolves the quest not by locating God in an external heaven but by recognizing the divine as an immanent force, alive in both nature and the self. This inward turn is characteristic of Carman’s mysticism, which aligns with Emerson’s assertion in Nature (1836) that "the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me."

Themes

1. Divine Immanence vs. Transcendence

Unlike traditional religious poetry that situates God in a remote heaven, Vestigia suggests that the divine is embedded in the world. The footprints, voice, and hand of God are all encountered within the natural landscape, implying that the sacred is not separate from the material realm but interwoven with it. This perspective is deeply pantheistic, echoing Spinoza’s conception of God as synonymous with nature itself.

2. The Ephemeral and the Eternal

The poem’s imagery—twilight, a fleeting breeze, a sunset—emphasizes transience, yet these momentary phenomena become portals to the eternal. The speaker’s realization that "God gives us Heaven here and now" (line 11) suggests that spiritual fulfillment is not deferred to an afterlife but available in present experience. This theme resonates with the Romantic privileging of the "here and now," as seen in Wordsworth’s "spots of time" or Keats’s "negative capability."

3. The Transformative Power of Beauty

The closing lines shift from passive observation to active engagement: the speaker longs for a "part / In making saving Beauty be" (lines 17–18). This suggests that the encounter with the divine is not merely contemplative but calls for creative participation. Beauty, in Carman’s vision, is not just an aesthetic pleasure but a redemptive force, aligning with the Keatsian notion that "Beauty is truth, truth beauty."

Comparative Analysis

Carman’s Vestigia can be fruitfully compared to several other works in the nature-mysticism tradition:

-

Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey: Both poems depict a moment of spiritual awakening through nature, though Wordsworth’s tone is more meditative and retrospective, while Carman’s is immediate and lyrical.

-

Emerson’s The Rhodora: Like Vestigia, Emerson’s poem finds the divine in a single flower, asking, "If eyes were made for seeing, / Then Beauty is its own excuse for being." Both poets suggest that nature’s beauty is self-justifying and revelatory.

-

Hopkins’ God’s Grandeur: Hopkins’ sonnet shares Carman’s theme of divine immanence, though his language is more ecstatic and his imagery more charged with Christian symbolism.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Underpinnings

The poem’s emotional power lies in its quiet intensity. Unlike dramatic religious epiphanies, Carman’s revelation is gentle, almost understated—a hand lightly resting on the brow, a voice heard in birdsong. This restraint makes the moment feel intimate and authentic, avoiding the pitfalls of sentimentality.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with process theology, which emphasizes God’s presence in the unfolding of the natural world rather than as a static, distant ruler. The speaker’s journey mirrors the mystic’s path: initial seeking, apparent absence, gradual recognition, and finally, integration of the divine into the self.

Conclusion

Vestigia is a masterful synthesis of Romantic lyricism, Transcendentalist philosophy, and personal mysticism. Through its precise imagery, sensory richness, and thematic depth, the poem transforms a simple walk in nature into a profound spiritual encounter. Carman’s vision is neither dogmatic nor vague; it offers a theology of immanence that remains compelling in an age of ecological awareness and spiritual seeking.

Ultimately, the poem’s greatest achievement is its ability to make the sacred feel near—not in distant heavens, but in the scarlet lily, the hermit thrush’s song, and the quiet glow of sunset. In doing so, Vestigia invites readers to reconsider where and how they might find their own traces of the divine.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!