Old Rhythm and Rhyme

Ella Wheeler Wilcox

1850 to 1919

They tell me new methods now govern the Muses,

The modes of expression have changed with the times;

That low is the rank of the poet who uses

The old-fashioned verse with intentional rhymes.

And quite out of date, too, is rhythmical metre;

The critics declare it an insult to art.

But oh! the sweet swing of it, oh! the clear ring of it,

Oh the great pulse of it, right from the heart,

Art or no art.

I sat by the side of that old poet, Ocean,

And counted the billows that broke on the rocks;

The tide lilted in with a rhythmical motion;

The sea-gulls dipped downward in time-keeping flocks.

I watched while a giant wave gathered its forces,

And then on the gray granite precipice burst;

And I knew as I counted, while other waves mounted,

I knew the tenth billow would rhyme with the first.

Below in the village a church bell was chiming,

And back in the woodland a little bird sang;

And, doubt it who will, yet those two sounds were rhyming,

As out o'er the hill-tops they echoed and rang.

The Wind and the Trees fell to talking together;

And nothing they said was didactic or terse;

But everything spoken was told in unbroken

And beautiful rhyming and rhythmical verse.

So rhythm I hail it, though critics assail it,

And hold melting rhymes as an insult to art,

For oh! the sweet swing of it, oh! the dear ring of it,

Oh! the strong pulse of it, right from the heart,

Art or no art.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox's Old Rhythm and Rhyme

Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s Old Rhythm and Rhyme is a defiant celebration of traditional poetic forms in an era increasingly dominated by free verse and modernist experimentation. Written during a period of significant literary transition—the late 19th and early 20th centuries—the poem articulates a passionate defense of rhythm and rhyme as natural, emotionally resonant, and artistically vital. Wilcox, often dismissed by highbrow critics for her accessible and sentimental style, here crafts a work that is both a manifesto and a lyrical meditation on the organic origins of poetic form.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact. Additionally, we will consider Wilcox’s position in the literary landscape, the philosophical underpinnings of her argument, and the ways in which her work engages with broader debates about art and authenticity.

Historical and Cultural Context

The late 19th century saw dramatic shifts in poetic conventions. The rise of free verse, championed by poets like Walt Whitman and later by the Modernists, challenged the dominance of structured meter and end-rhyme. Critics increasingly viewed traditional forms as artificial constraints, favoring instead a poetry that mirrored the irregular cadences of natural speech.

Wilcox, however, remained committed to the musicality of verse. Her popularity with the general public contrasted sharply with the disdain of literary elites, who often derided her work as simplistic or overly sentimental. Old Rhythm and Rhyme can thus be read as both a personal rebuttal to her detractors and a broader argument for the enduring relevance of traditional forms.

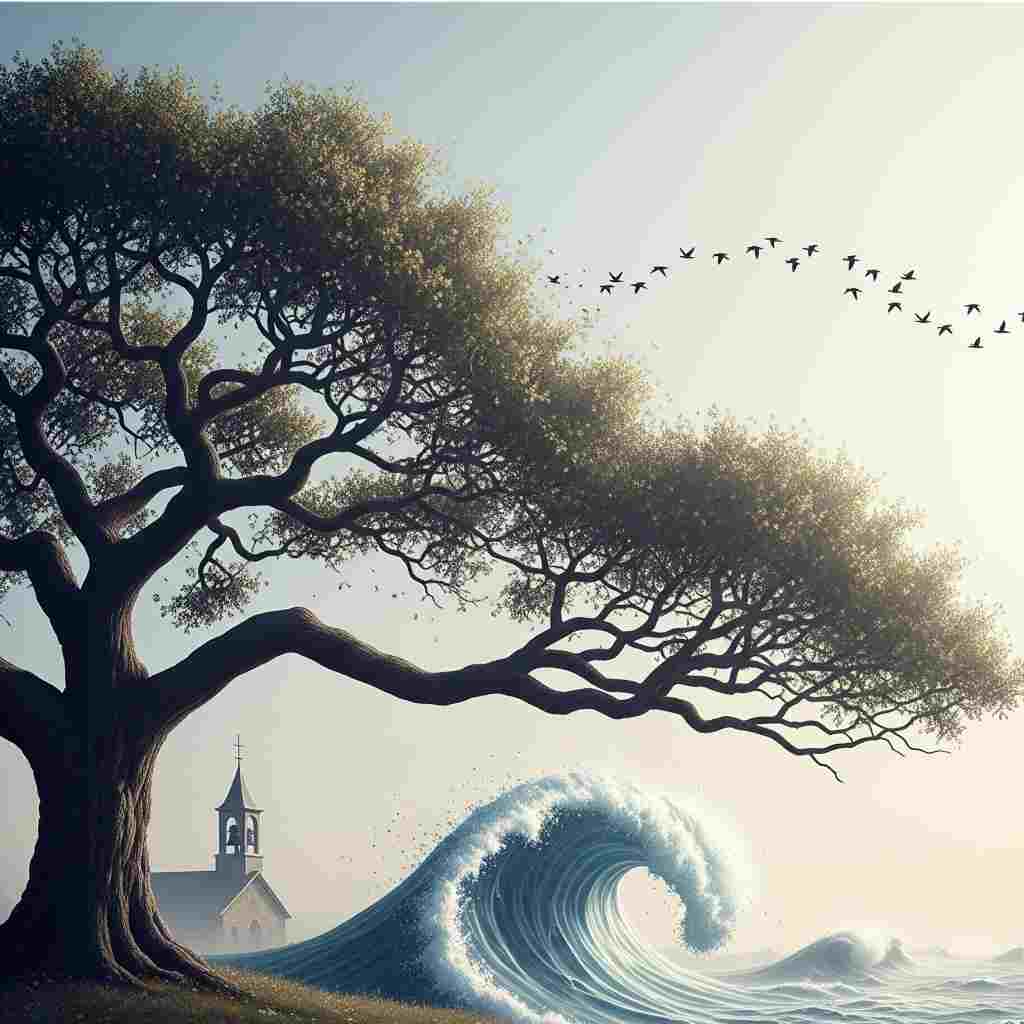

The poem’s imagery—the ocean, church bells, birdsong, and wind—evokes a Romantic sensibility, aligning Wilcox with an earlier poetic tradition that saw nature itself as inherently rhythmic and harmonious. In doing so, she suggests that formal poetry is not an artificial imposition but a reflection of the world’s intrinsic patterns.

Literary Devices and Structure

Wilcox employs a variety of literary devices to reinforce her argument, most notably anaphora, parallelism, and imagery. The repetition of “Oh! the sweet swing of it, oh! the dear ring of it, / Oh! the strong pulse of it, right from the heart” serves as a refrain, emphasizing the visceral, almost physical pleasure of rhythmic verse. The parallel structure of these lines creates a musicality that enacts the very quality she praises.

The poem’s imagery is drawn from nature and sound: the “billows that broke on the rocks,” the “sea-gulls dipped downward in time-keeping flocks,” the “church bell chiming,” and the “little bird” whose song rhymes with the bell. These images serve a dual purpose: they illustrate the natural origins of rhythm and rhyme, and they create a sensory richness that makes her argument felt rather than merely stated.

Wilcox also uses personification effectively, particularly in the lines:

The Wind and the Trees fell to talking together;

And nothing they said was didactic or terse;

But everything spoken was told in unbroken

And beautiful rhyming and rhythmical verse.

Here, nature itself becomes a poet, its utterances spontaneous yet perfectly structured. This reinforces her thesis that rhythm and rhyme are not contrivances but organic expressions of life’s inherent music.

Themes

1. The Naturalness of Rhythm and Rhyme

Wilcox’s central argument is that rhythm and rhyme are not artificial constructs but fundamental aspects of the natural world. The ocean’s waves, the call-and-response of birds and bells, the dialogue of wind and trees—all exhibit the same patterns that poets have formalized into verse. In this way, she aligns herself with the Romantic tradition of Wordsworth and Coleridge, who saw poetry as an extension of natural harmony.

2. The Conflict Between Popular and Elite Art

The poem opens with a critique of literary gatekeeping:

They tell me new methods now govern the Muses,

The modes of expression have changed with the times;

That low is the rank of the poet who uses

The old-fashioned verse with intentional rhymes.

Here, Wilcox positions herself against critics who dismiss traditional forms as outdated. Her insistence on the “strong pulse of it, right from the heart” suggests that true art should be judged not by its adherence to fashion but by its emotional authenticity.

3. The Emotional Power of Form

For Wilcox, the pleasure of rhythm and rhyme is not merely intellectual but somatic—felt in the body. The “sweet swing,” the “dear ring,” and the “strong pulse” evoke a physical response, underscoring her belief that poetry should move its audience viscerally. This aligns with 19th-century ideas about poetry’s connection to music and dance, where meter and sound patterns elicit direct emotional reactions.

Comparative Analysis

Wilcox’s defense of traditional forms invites comparison with other poets who resisted modernist experimentation. Edgar Allan Poe, for instance, famously argued in The Philosophy of Composition that poetry should prioritize musicality and structured beauty. Similarly, Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s meticulous craftsmanship stands in contrast to the free-verse experiments of his contemporaries.

However, Wilcox’s populist stance also echoes Whitman’s democratic ethos—despite their formal differences. Whitman celebrated the organic and the spontaneous, much as Wilcox does, though he rejected regular meter. Yet both share a belief in poetry as an embodied, sensory experience rather than an abstract intellectual exercise.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Wilcox’s own career sheds light on her poetic stance. Often marginalized by the literary establishment, she found immense popularity with everyday readers. This tension between critical dismissal and public adoration likely fueled her defiant tone in Old Rhythm and Rhyme. Her poem can be read as a vindication of her own aesthetic choices—a declaration that art’s value lies not in elite approval but in its ability to resonate deeply.

Philosophically, her argument touches on the divide between classical formalism (which sees beauty in order and symmetry) and Romantic expressivism (which privileges raw emotion). Wilcox bridges these traditions, asserting that form and feeling are not opposed but inextricably linked.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s emotional power lies in its exuberance. Unlike a dry theoretical defense of formalism, Wilcox’s verse thrums with vitality. The repetition of “Oh!” conveys almost ecstatic appreciation, while the imagery of crashing waves and chiming bells creates an immersive soundscape. The reader is invited not just to understand her argument but to feel it—to experience the joy of rhythm as she does.

Conclusion

Old Rhythm and Rhyme is more than a nostalgic paean to traditional poetry; it is a robust philosophical and aesthetic statement. Wilcox locates the origins of poetic form in the natural world, argues for its emotional necessity, and challenges the elitism of avant-garde criticism. While her work was often dismissed in her time, this poem remains a compelling testament to the enduring power of rhythm and rhyme—not as rigid constraints, but as living, breathing expressions of human (and natural) vitality.

In an age where poetic forms continue to evolve, Wilcox’s words remind us that the “strong pulse” of rhythm, when wielded with sincerity, will always find its way to the heart.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!