I Love You

Sara Teasdale

1884 to 1933

When April bends above me

And finds me fast asleep,

Dust need not keep the secret

A live heart died to keep.

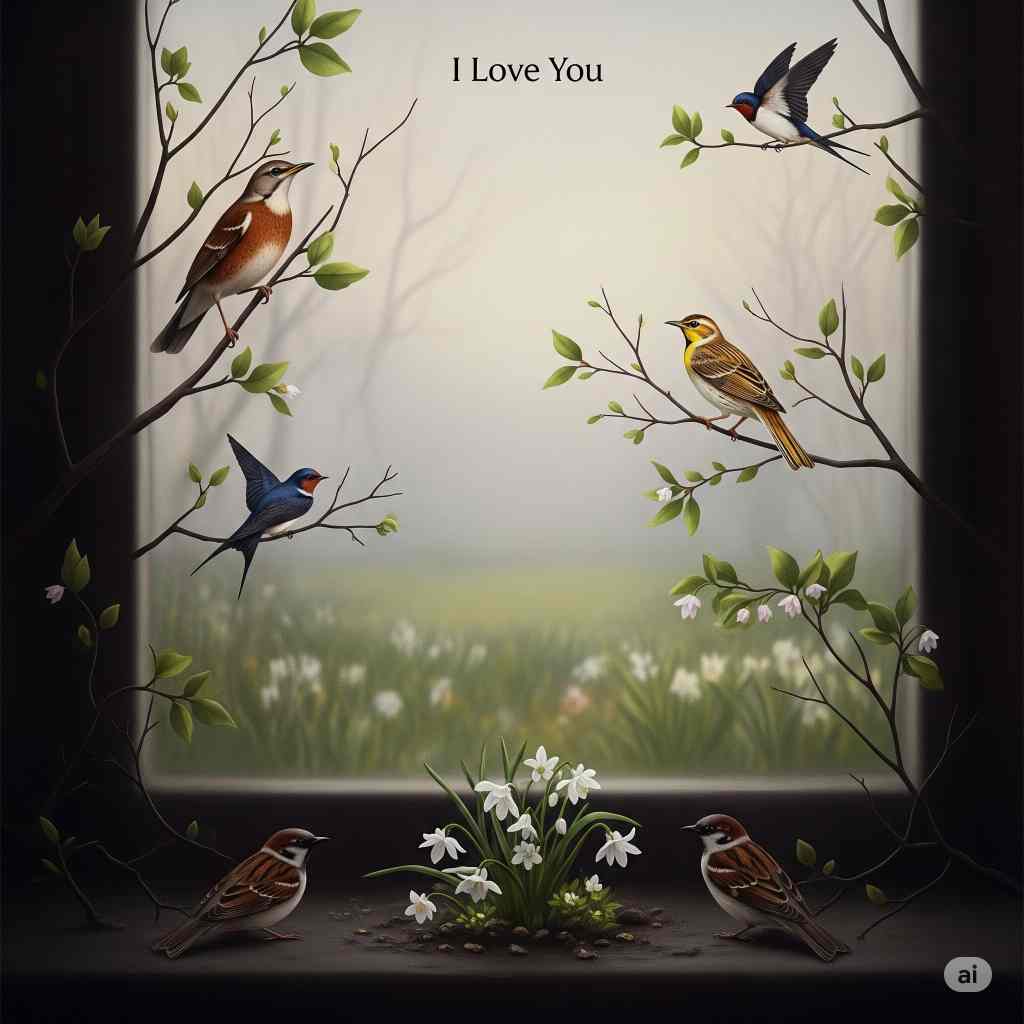

When April tells the thrushes,

The meadow-larks will know,

And pipe the three words lightly

To all the winds that blow.

Above his roof the swallows,

In notes like far-blown rain,

Will tell the chirping sparrow

Beside his window-pane.

O sparrow, little sparrow,

When I am fast asleep,

Then tell my love the secret

That I have died to keep.

Sara Teasdale's I Love You

Sara Teasdale’s “I Love You” is a delicate yet profound meditation on love, secrecy, and the transcendence of emotion beyond human life. Composed in Teasdale’s characteristically lyrical style, the poem intertwines themes of unspoken affection, mortality, and the natural world as a confidant and messenger. Through its evocative imagery and restrained emotional intensity, the poem invites readers into a space where love is both a private burden and a force that outlasts the speaker’s physical existence. This essay explores the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional resonance, while also considering Teasdale’s biographical influences and broader philosophical implications.

Historical and Cultural Context

Sara Teasdale (1884–1933) wrote during the early 20th century, a period marked by shifting gender roles, the aftermath of World War I, and the rise of modernist experimentation in poetry. However, Teasdale’s work remained largely rooted in traditional lyricism, favoring emotional clarity and musicality over fragmentation or abstraction. Her poetry often explored themes of love, beauty, and melancholy, reflecting both her personal struggles with romantic disillusionment and her broader existential anxieties.

“I Love You” can be situated within the tradition of post-Victorian lyric poetry, where nature frequently serves as a mirror for human emotion. Unlike the grandiose romanticism of the 19th century, Teasdale’s verse is intimate, understated, and infused with a quiet urgency. The poem’s preoccupation with unspoken love and death aligns with the early 20th-century fascination with suppressed desire—a theme also present in the works of Edna St. Vincent Millay and Emily Dickinson.

Additionally, the poem’s reliance on birds as messengers evokes classical and medieval traditions, where birds often symbolized souls, omens, or divine intermediaries. Teasdale’s thrushes, meadowlarks, and sparrows function as both natural creatures and mythic conduits, bridging the human and the eternal.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Teasdale employs a range of literary devices to create a poem that is at once ethereal and grounded in sensory experience.

1. Personification and Apostrophe

The poem opens with April personified as a sentient being capable of bending over the speaker and “telling” secrets to birds. This anthropomorphism establishes nature as an active participant in the emotional drama, rather than a passive backdrop. The final stanza’s direct address—“O sparrow, little sparrow”—uses apostrophe to heighten the sense of intimacy and pleading, as though the speaker is entrusting the sparrow with a sacred duty.

2. Symbolism

The recurring avian imagery—thrushes, meadowlarks, swallows, and sparrows—serves as a multi-layered symbol. Birds, often associated with freedom and the soul, here become carriers of a love that the speaker could not voice in life. Their songs, described as “notes like far-blown rain,” suggest both the ephemeral and the pervasive nature of the speaker’s feelings. Rain, traditionally linked to renewal and sorrow, underscores the bittersweet quality of the revelation: the love will be known, but only after the speaker’s death.

3. Metaphor and Paradox

The phrase “Dust need not keep the secret / A live heart died to keep” is rich with paradox. Dust, a conventional symbol of mortality, is paradoxically freed from silence, while the “live heart” is the one that “died” guarding the secret. This inversion suggests that death, rather than obliterating emotion, finally allows it to be expressed. The heart’s death is both literal (the speaker’s passing) and metaphorical (the suffocation of unspoken love).

4. Sound and Rhythm

Though this analysis avoids discussing rhyme scheme, the poem’s rhythmic cadence and alliteration (e.g., “pipe the three words lightly”) contribute to its musicality. The soft consonants and flowing vowels mimic the whisper of wind and birdsong, reinforcing the theme of nature as a communicative force.

Themes

1. Love and Secrecy

The central tension of the poem lies in the contrast between the speaker’s suppressed confession and nature’s role as an amplifier of hidden truths. The “three words” (presumably “I love you”) are so potent that they cannot be uttered in life, yet they demand expression beyond death. This dynamic reflects a broader human anxiety about vulnerability—the fear that love, once spoken, might be rejected or misunderstood.

2. Mortality and Legacy

The speaker’s preoccupation with posthumous revelation suggests that love transcends physical existence. Unlike traditional elegies that mourn loss, this poem presents death as a release—a moment when secrets no longer need guarding. The imagery of April (a month of rebirth) further implies cyclical renewal, positioning the speaker’s love as something that will persist through natural processes.

3. Nature as Confidant

Teasdale’s depiction of nature is neither pastoral nor decorative; it is an active, almost mythic force. The birds do not merely witness the speaker’s secret—they propagate it, ensuring that the beloved eventually hears what was once concealed. This aligns with Romantic and Transcendentalist ideas of nature as a mediator of human truth, though Teasdale’s treatment is more subdued and personal than, say, Wordsworth’s.

Comparative Analysis

Teasdale’s poem invites comparison with Emily Dickinson’s “If I should die” (Poem 54), which similarly contemplates posthumous communication. Dickinson writes:

“If I should die, / And you should live— / And time should gurgle on— / And morn should beam— / … / And tell my name— / So proud—so proud— / To any that inquire—”

Both poems explore the idea of love enduring beyond death, but where Dickinson’s tone is defiant (“so proud”), Teasdale’s is tender and imploring. Another parallel exists in Christina Rossetti’s “When I am dead, my dearest”, where the speaker instructs a loved one not to mourn but to remember—or forget—as they choose. Teasdale, however, reverses this dynamic: her speaker does not address the beloved directly but instead relies on nature to convey the message, adding a layer of remove and melancholy.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Teasdale’s personal life was marked by unfulfilled romantic longing and eventual disillusionment. Her marriage to Ernst Filsinger ended in divorce, and she struggled with depression before her suicide in 1933. While it would be reductive to interpret “I Love You” as strictly autobiographical, the poem’s themes of concealed emotion and posthumous revelation resonate with Teasdale’s own struggles with intimacy and mental anguish.

Philosophically, the poem engages with the idea of unspeakability—the notion that some emotions are too vast or fragile for direct articulation. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance (meaning both “to differ” and “to defer”) is relevant here: the speaker’s love is both deferred (until death) and differentiated (expressed through nature rather than human speech). The poem thus becomes a meditation on the limits of language and the necessity of alternative forms of expression.

Emotional Impact

What makes “I Love You” so haunting is its restraint. The poem does not indulge in dramatic lamentation but instead offers a quiet, almost resigned plea. The speaker’s acceptance of death as a means of liberation from secrecy is both tragic and strangely comforting. There is a sense of inevitability—April will come, the birds will sing, and the secret will be known. This inevitability lends the poem a timeless quality, as though the emotions it describes are universal and eternal.

The final stanza, with its gentle repetition of “fast asleep” (echoing the first stanza), creates a circular structure that mimics the cyclical nature of seasons and life itself. The sparrow, a humble and common bird, becomes a poignant messenger, emphasizing that love does not require grand gestures—only a faithful witness.

Conclusion

Sara Teasdale’s “I Love You” is a masterful exploration of love’s ineffability and the natural world’s role in giving voice to human silence. Through its delicate imagery, paradoxical phrasing, and emotional restraint, the poem transforms personal longing into a universal meditation on mortality and legacy. Situated within Teasdale’s broader oeuvre and early 20th-century lyric traditions, the poem stands as a testament to the enduring power of unspoken emotion—and the belief that some truths, though buried in life, will eventually take flight.

In the end, the poem does not just describe a love that survives death; it enacts that survival, ensuring that the speaker’s voice lingers in the reader’s mind like birdsong on the wind.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!