Bill

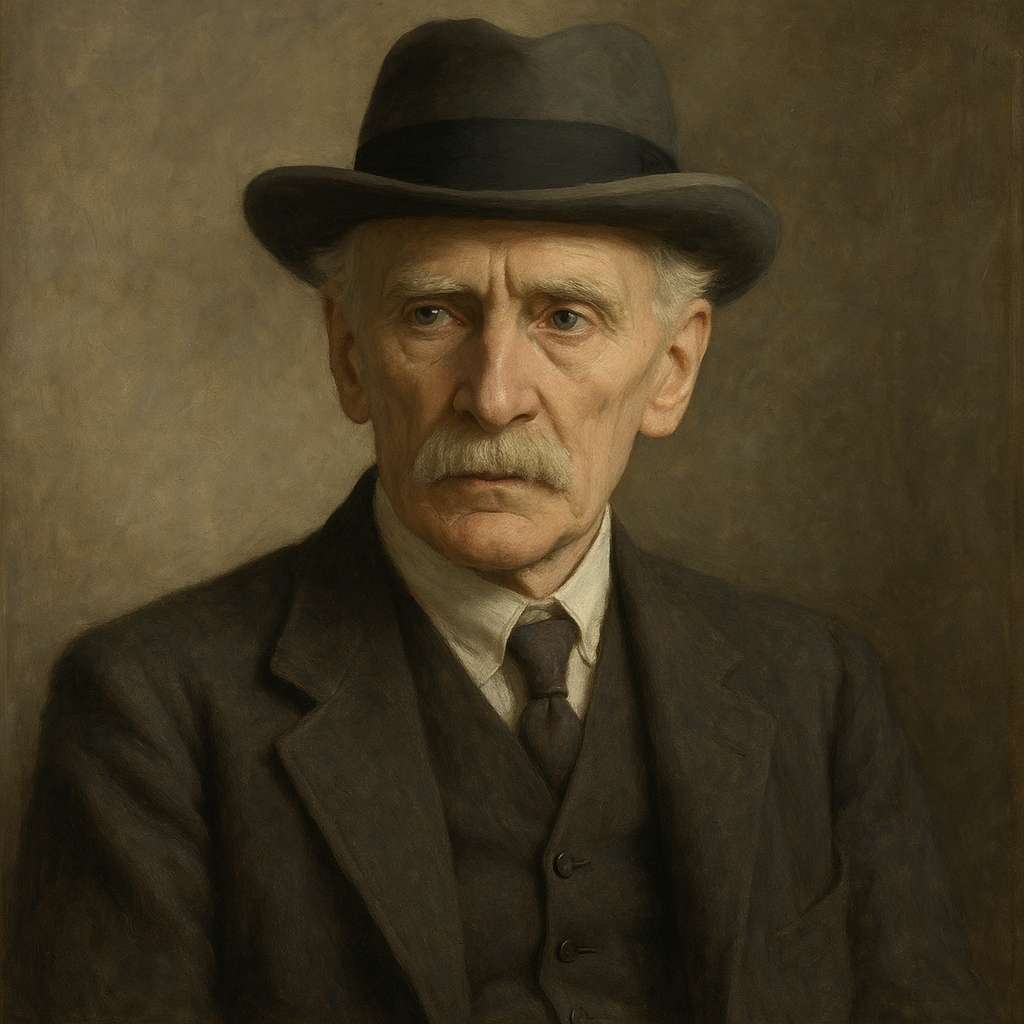

John Masefield

1878 to 1967

He lay dead on the cluttered deck and stared at the cold skies,

With never a friend to mourn for him nor a hand to close his eyes:

‘Bill, he’s dead,’ was all they said; ‘he’s dead, ’n’ there he lies.’

The mate came forrard at seven bells and spat across the rail:

‘Just lash him up wi’ some holystone in a clout o’ rotten sail,

’N’, rot ye, get a gait on ye, ye’re slower’n a bloody snail!’

When the rising moon was a copper disc and the sea was a strip of steel,

We dumped him down to the swaying weeds ten fathom beneath the keel.

‘It’s rough about Bill,’ the fo’c’s’le said, ‘we’ll have to stand his wheel.’

John Masefield's Bill

John Masefield’s Bill is a stark and unflinching portrayal of death at sea, rendered with a raw simplicity that belies its emotional depth. Written in the early 20th century, the poem reflects Masefield’s firsthand experience of maritime life, as well as his broader preoccupation with the lives of ordinary people and the inevitability of mortality. Masefield, who served as a sailor in his youth, brings an authenticity to the poem that resonates with readers, offering a glimpse into the often-overlooked world of seafaring laborers. The poem’s brevity and directness are deceptive, as it encapsulates profound themes of isolation, indifference, and the fragility of human life.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate Bill, it is essential to situate it within its historical and cultural context. The early 20th century was a period of transition, marked by the decline of the age of sail and the rise of steam-powered ships. Sailors like Bill were part of a dying breed, their lives governed by the rhythms of the sea and the harsh discipline of shipboard life. Masefield, who worked on merchant ships as a young man, was intimately familiar with this world, and his poetry often reflects the struggles and triumphs of those who lived and died at sea.

The poem’s setting—a cluttered deck, a rising moon, and a steel-like sea—evokes the timelessness of the maritime experience, while its language and tone capture the gritty reality of life aboard a ship. The casual brutality of the mate’s orders and the crew’s matter-of-fact response to Bill’s death reflect the desensitization that often accompanied such a life. In this context, death is not a grand or heroic event but a mundane occurrence, handled with the same efficiency as any other task.

Literary Devices and Structure

Masefield’s use of language in Bill is both economical and evocative. The poem is written in free verse, eschewing traditional rhyme and meter in favor of a more naturalistic and conversational tone. This choice reflects the poem’s subject matter, as the irregular rhythm mirrors the ebb and flow of the sea and the unpredictability of life aboard a ship. The lack of formal structure also underscores the poem’s themes of impermanence and disorder.

One of the most striking features of the poem is its use of dialect and colloquial language. Phrases like “’n’ there he lies,” “wi’ some holystone,” and “rot ye” immerse the reader in the world of the sailors, lending the poem an air of authenticity. This linguistic choice not only grounds the poem in its historical context but also highlights the social and cultural divide between the sailors and the world beyond the ship. The mate’s harsh commands and the crew’s terse responses reveal a hierarchy of power and a culture of survival, where empathy is a luxury few can afford.

Masefield also employs vivid imagery to convey the poem’s emotional and thematic depth. The description of Bill lying “dead on the cluttered deck” evokes a sense of chaos and neglect, while the “cold skies” above suggest an indifferent universe. The rising moon, depicted as a “copper disc,” and the sea, described as a “strip of steel,” create a stark and almost metallic landscape, emphasizing the harshness of the sailors’ environment. These images serve to heighten the poem’s emotional impact, as they contrast sharply with the human tragedy at its center.

Themes and Emotional Impact

At its core, Bill is a meditation on death and the human response to it. The poem’s opening lines—“He lay dead on the cluttered deck and stared at the cold skies, / With never a friend to mourn for him nor a hand to close his eyes”—immediately establish a tone of isolation and neglect. Bill’s death is not marked by ceremony or grief but by indifference and pragmatism. The crew’s response—“‘Bill, he’s dead,’ was all they said; ‘he’s dead, ’n’ there he lies’”—underscores the dehumanizing effects of their environment, where death is a routine occurrence.

This theme of indifference is further reinforced by the mate’s callous orders to dispose of Bill’s body. The use of holystone (a abrasive stone used for scrubbing decks) and “rotten sail” as burial shrouds symbolizes the degradation of Bill’s humanity in death. The mate’s harsh language—“rot ye, get a gait on ye, ye’re slower’n a bloody snail!”—reveals a world where efficiency and discipline take precedence over compassion. Even in death, Bill is reduced to a mere inconvenience, a problem to be solved as quickly as possible.

Yet, beneath this surface of indifference lies a subtle undercurrent of camaraderie and resignation. The fo’c’s’le’s remark—“‘It’s rough about Bill,’ the fo’c’s’le said, ‘we’ll have to stand his wheel’”—suggests a recognition of Bill’s humanity, even if it is expressed in practical terms. The phrase “stand his wheel” implies that Bill’s duties will now fall to his fellow sailors, a reminder of the interconnectedness of their lives. In this way, the poem captures the complex interplay of callousness and solidarity that characterizes life at sea.

The emotional impact of Bill lies in its ability to evoke both pity and unease. The poem forces readers to confront the harsh realities of a world where death is stripped of its dignity and humanity is often sacrificed to the demands of survival. At the same time, it invites reflection on the ways in which people cope with such realities, whether through indifference, humor, or quiet resignation.

Conclusion

John Masefield’s Bill is a powerful and evocative poem that captures the harshness of life at sea and the fragility of human existence. Through its use of vivid imagery, colloquial language, and stark realism, the poem offers a poignant meditation on death, isolation, and the resilience of the human spirit. While its subject matter is undeniably grim, the poem’s emotional depth and authenticity make it a compelling and enduring work of art.

Masefield’s ability to convey the complexities of the human experience in such a concise and unadorned manner is a testament to his skill as a poet. Bill reminds us of the power of poetry to illuminate the darker corners of our world and to connect us, however briefly, with the lives of those who inhabit them. In its exploration of death and indifference, the poem challenges us to consider our own responses to mortality and the ways in which we navigate the often harsh realities of life. In doing so, it affirms the enduring relevance of poetry as a means of understanding and engaging with the world around us.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!