Color

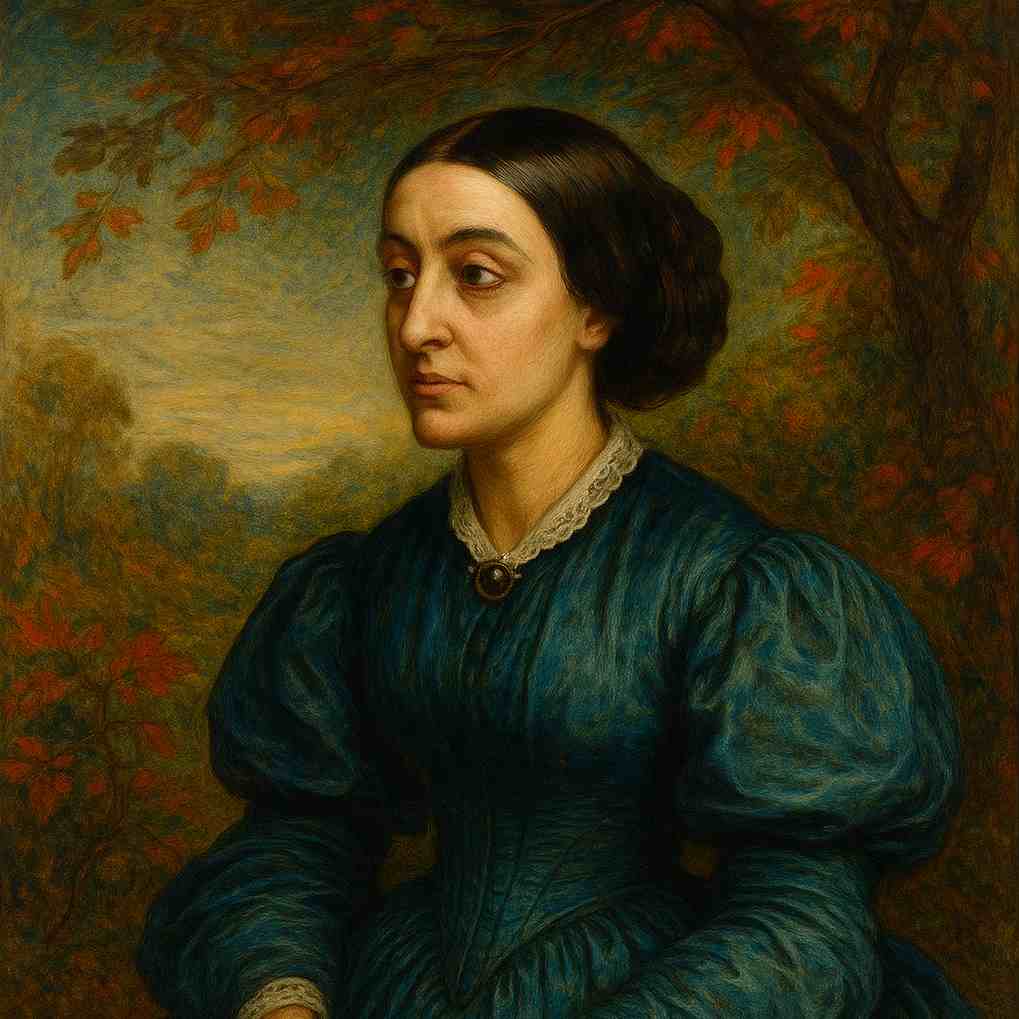

Christina Rossetti

1830 to 1894

What is pink? a rose is pink

By a fountain's brink.

What is red? a poppy's red

In its barley bed.

What is blue? the sky is blue

Where the clouds float thro'.

What is white? a swan is white

Sailing in the light.

What is yellow? pears are yellow,

Rich and ripe and mellow.

What is green? the grass is green,

With small flowers between.

What is violet? clouds are violet

In the summer twilight.

What is orange? Why, an orange,

Just an orange!

Christina Rossetti's Color

Introduction

Christina Rossetti's poem "Color" presents itself as a seemingly simple exploration of the visual spectrum through natural imagery. However, beneath its childlike question-and-answer structure lies a complex interplay of sensory perception, linguistic association, and symbolic meaning. This essay aims to unpack the various layers of Rossetti's work, examining its formal structure, thematic concerns, and place within the broader context of Victorian poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Formal Structure and Linguistic Playfulness

At first glance, "Color" appears to be structured as a series of simple questions and answers, reminiscent of a children's primer or nursery rhyme. Each stanza follows a consistent pattern:

- A question asking about a color

- An answer identifying an object or natural phenomenon of that color

- A qualifying phrase or clause that provides additional context or imagery

This repetitive structure creates a rhythmic cadence that propels the reader through the poem, mirroring the way one might move through a colorful landscape or art gallery. The use of rhyming couplets (e.g., "pink/brink," "red/bed") further enhances this musicality, lending the poem an air of playful lyricism.

However, Rossetti's linguistic choices are far from simplistic. The poem demonstrates a masterful use of assonance and consonance, creating a rich auditory experience that complements its visual focus. For example, the line "Rich and ripe and mellow" uses the repetition of the "r" sound to evoke the luscious texture of a pear, while the soft "m" and "l" sounds mimic the fruit's smooth skin.

Sensory Synesthesia and Perceptual Exploration

While the poem ostensibly focuses on colors, Rossetti deftly incorporates multiple sensory experiences, creating a synesthetic effect that blurs the boundaries between sight, sound, touch, and even taste. This multisensory approach is evident in lines such as:

- "By a fountain's brink" (auditory: the sound of water)

- "Rich and ripe and mellow" (tactile and gustatory: the texture and taste of fruit)

- "Sailing in the light" (kinesthetic: the motion of the swan)

This sensory interplay invites the reader to engage with the poem not just as a visual exercise, but as a full-bodied experience of the natural world. It also raises questions about the nature of perception itself: How do our various senses inform and influence each other? To what extent is our understanding of color shaped by our other sensory experiences?

Natural Imagery and the Pre-Raphaelite Influence

Rossetti's choice of natural imagery to represent each color is firmly rooted in the Pre-Raphaelite tradition, of which she was a key figure. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848, emphasized a return to detailed, vibrant depictions of the natural world, often with symbolic or spiritual undertones. In "Color," we see this influence in the vivid, almost painterly descriptions of flowers, fruits, and landscapes.

Each color is associated with a specific natural element:

- Pink: rose

- Red: poppy

- Blue: sky

- White: swan

- Yellow: pears

- Green: grass

- Violet: clouds at twilight

- Orange: the fruit itself

These choices are not arbitrary but carefully selected for their cultural and symbolic resonances. The rose, for instance, has long been associated with love and beauty in Western culture, while the poppy can symbolize both sleep and remembrance. The swan, traditionally a symbol of grace and purity, is presented here in a moment of ethereal beauty, "sailing in the light."

Temporal and Spatial Dimensions

Despite its apparent simplicity, "Color" subtly incorporates both temporal and spatial dimensions. The poem moves from earth (rose, poppy) to sky (blue sky, clouds), then back to earth (swan on water, pears, grass) before returning to the sky (violet clouds). This vertical movement creates a sense of expansiveness, encouraging the reader to consider the full scope of the natural world.

There's also a temporal progression embedded in the poem. It begins with the vibrant colors of full daylight (pink, red, blue) and ends with the "summer twilight," suggesting the passage of time. This temporal shift adds depth to the poem, hinting at the cyclical nature of days and seasons, and perhaps even serving as a metaphor for the stages of life.

The Enigmatic Conclusion

The poem's final stanza stands out for its departure from the established pattern:

"What is orange? Why, an orange, Just an orange!"

This abrupt shift in tone and structure serves multiple purposes:

- It injects a note of humor and surprise, preventing the poem from becoming too predictable or saccharine.

- It draws attention to the arbitrary nature of language and naming. While other colors are described through simile or metaphor, orange is simply itself, highlighting the sometimes circular logic of linguistic definition.

- It potentially serves as a meta-commentary on the act of poetic description. After a series of elaborate natural images, Rossetti seems to throw up her hands, as if to say, "Sometimes a thing is just what it is."

This conclusion invites various interpretations. Is it a playful jab at the limitations of language? A nod to the idea that some experiences defy poetic elaboration? Or perhaps a subtle critique of the very exercise of cataloging and categorizing the natural world?

Conclusion: Beyond Simple Colors

"Color" reveals itself to be far more than a simple catalog of hues and their natural manifestations. Through its intricate interplay of sound and imagery, its evocation of multiple senses, and its subtle exploration of space and time, the poem invites us to consider the complex ways in which we perceive and categorize the world around us.

Rossetti's work challenges us to look beyond the surface, to consider how our understanding of something as seemingly straightforward as color is shaped by cultural associations, personal experiences, and the interplay of our senses. In doing so, she transforms a childlike exercise in naming colors into a profound meditation on perception, language, and our relationship with the natural world.

In the broader context of Victorian poetry, "Color" stands as a testament to the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to vivid natural imagery while also pointing towards the more experimental, self-reflexive poetry that would emerge in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It demonstrates Rossetti's ability to work within traditional forms while subtly subverting them, creating a poem that is at once accessible and deeply complex.

Ultimately, "Color" serves as a reminder of the power of poetry to transform our perception of the everyday world, inviting us to see the extraordinary in the ordinary, the complex in the simple, and the universal in the particular.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!