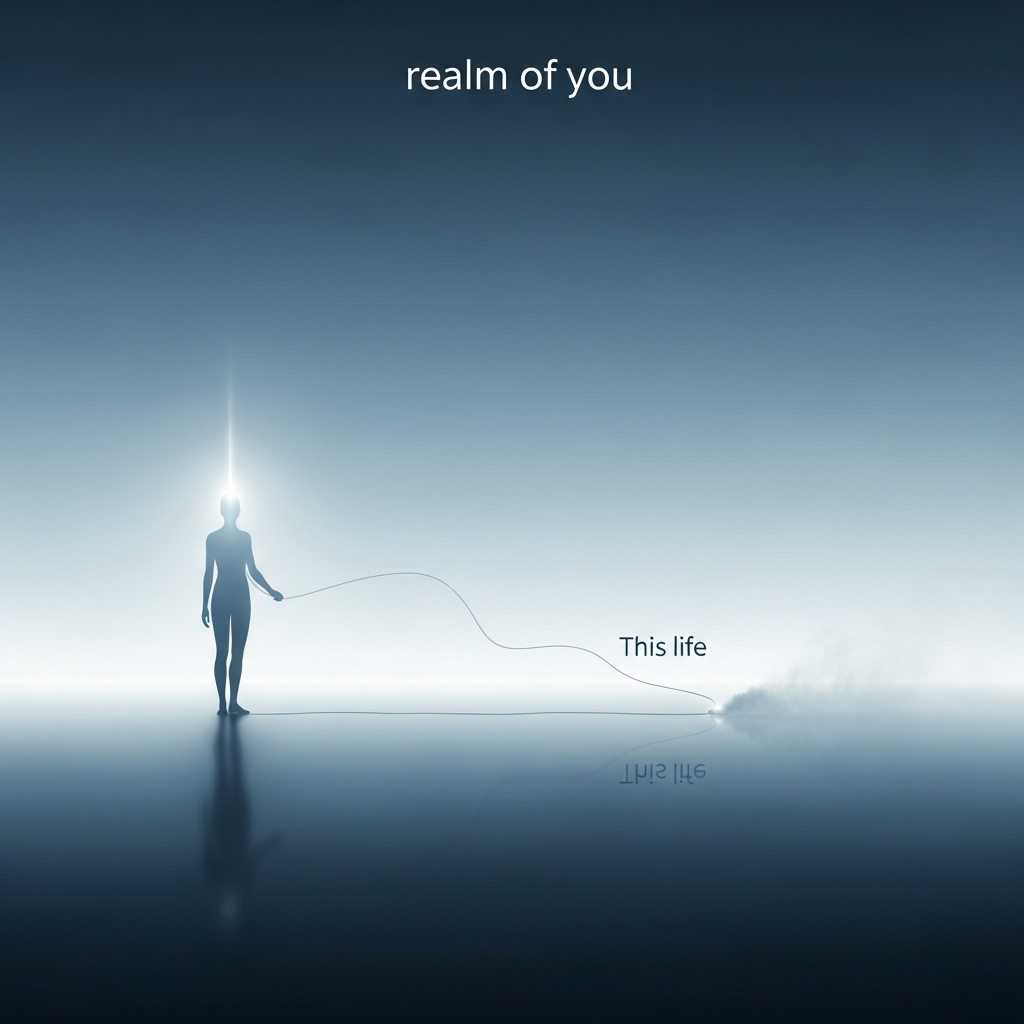

I have no life but this

Emily Dickinson

1830 to 1886

I have no life but this,

To lead it here;

Nor any death, but lest

Dispelled from there;

Nor tie to earths to come,

Nor action new,

Except through this extent,

The realm of you.

Emily Dickinson's I have no life but this

Emily Dickinson’s poetry is renowned for its enigmatic brevity, philosophical depth, and emotional intensity. Among her vast body of work, the poem “I have no life but this” stands as a striking meditation on existence, attachment, and the boundaries of selfhood. Composed in Dickinson’s characteristic compact style, the poem distills profound existential and emotional truths into just eight lines. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its intricate literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance, while also considering Dickinson’s biographical influences and possible philosophical underpinnings.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate Dickinson’s poem, one must situate it within the broader intellectual and cultural currents of 19th-century America. Dickinson wrote during a period of immense social and philosophical upheaval—the rise of Transcendentalism, the lingering influence of Puritan thought, and the growing tensions leading to the Civil War all shaped her worldview.

Dickinson was deeply influenced by the Transcendentalist movement, particularly the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who emphasized individualism, spiritual intuition, and the interconnectedness of all existence. However, unlike Emerson’s optimistic vision of self-reliance, Dickinson’s poetry often grapples with existential solitude and the limits of human connection. “I have no life but this” reflects this tension—it speaks to an intense, almost metaphysical dependence on another being, suggesting that the speaker’s entire existence is contingent upon a singular relationship.

Additionally, Dickinson’s reclusive lifestyle—she spent much of her adult life in relative seclusion in Amherst, Massachusetts—infused her poetry with a preoccupation with interiority. The poem’s introspective tone aligns with her broader fascination with the inner self, mortality, and the boundaries between the physical and spiritual realms.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, the poem is rich in literary techniques that amplify its emotional and philosophical weight.

1. Paradox and Duality

The poem opens with a paradox: “I have no life but this, / To lead it here.” The speaker simultaneously asserts existence (“I have no life but this”) and limitation (“To lead it here”). This duality is central to Dickinson’s poetic style—she often explores the coexistence of presence and absence, life and death, connection and isolation.

The second stanza deepens this paradox: “Nor any death, but lest / Dispelled from there.” Here, death is not an end but a fear of expulsion from a cherished state (“there”). The speaker’s existence is so bound to another that even death is redefined—it is not annihilation but severance from the beloved.

2. Metaphysical Conceit

The poem employs a metaphysical conceit—an extended metaphor that links abstract ideas with tangible imagery. The phrase “The realm of you” suggests that the beloved is not merely a person but an entire domain, a sovereign territory where the speaker’s life and actions are confined. This evokes John Donne’s metaphysical poetry, where lovers become worlds unto themselves (e.g., “The Good-Morrow”: “My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears”).

3. Negation and Restriction

Dickinson frequently uses negation to convey depth through absence. The repetition of “nor” (“Nor tie to earths to come, / Nor action new”) emphasizes constraint—the speaker’s future and agency are circumscribed by their devotion. This technique creates a sense of claustrophobic intensity, as if the speaker’s entire being is compressed into the space of this relationship.

4. Spatial Imagery

The poem’s imagery is deeply spatial: “here,” “there,” “extent,” “realm.” These terms construct a psychological landscape where existence is not a linear progression but a fixed locus. The speaker’s life is not expansive but contained within the beloved’s influence, reinforcing the theme of existential dependency.

Themes

1. Existential Dependence and Love

At its core, the poem explores the idea that one’s existence is contingent upon another. The speaker does not merely love; they exist solely within the “realm” of the beloved. This evokes philosophical notions of selfhood—does identity arise independently, or is it shaped entirely by relationships?

Dickinson’s treatment of love here is neither romantic nor sentimental but metaphysical. The beloved is not just a partner but the very condition of being. This aligns with Martin Heidegger’s concept of “Being-toward-death”—the idea that existence gains meaning through its finitude and connections. For the speaker, even death is only meaningful as a potential exile from this essential bond.

2. Limitation and Freedom

The poem oscillates between confinement and transcendence. The speaker’s life is restricted (“no life but this”), yet this restriction is also a form of transcendence—by existing entirely within the beloved’s “realm,” they escape conventional temporal and spatial bounds (“Nor tie to earths to come”). This paradox mirrors Dickinson’s broader preoccupation with the interplay between limitation and infinity, as seen in poems like “I dwell in Possibility.”

3. Death as Displacement

Unlike traditional depictions of death as an end, Dickinson presents it as a form of displacement (“Dispelled from there”). This suggests that the speaker’s greatest fear is not cessation but expulsion from the beloved’s presence. Theologically, this resonates with Puritan anxieties about divine abandonment, yet Dickinson secularizes the idea—the terror lies not in hell but in relational dissolution.

Comparative Analysis

Dickinson’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other works exploring existential dependency:

-

John Donne’s “The Sun Rising”: Both poems depict lovers as self-contained universes. However, Donne’s tone is triumphant (“She is all states, and all princes, I”), whereas Dickinson’s is more restrained and melancholic.

-

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 (“Let me not to the marriage of true minds”): Both examine love as a fixed, almost metaphysical force. Yet Shakespeare’s sonnet celebrates love’s constancy, while Dickinson’s poem conveys a more desperate fixation.

-

Sylvia Plath’s “Mad Girl’s Love Song”: Plath’s speaker also grapples with love as an all-consuming force (“I think I made you up inside my head”). Both poets blur the line between love and existential annihilation.

Biographical Insights

While Dickinson’s personal life remains shrouded in mystery, scholars have speculated about her intense (and possibly unrequited) attachments, particularly to her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert. The poem’s tone of absolute devotion could reflect Dickinson’s own experiences of emotional dependency.

Alternatively, the poem may not be about a human beloved at all but about God, poetry, or even the self. Dickinson often conflated human and divine love, and her work frequently blurs the boundaries between the spiritual and the personal.

Philosophical and Emotional Impact

The poem’s emotional power lies in its stark vulnerability. The speaker’s existence is so narrowly defined that its loss would be not just sorrow but erasure. This resonates with existentialist thought—Jean-Paul Sartre argued that humans define themselves through their choices and relationships; here, the speaker has relinquished all autonomy, making their being entirely relational.

Yet there is also a quiet defiance in the poem. By declaring “I have no life but this,” the speaker embraces their dependence, turning limitation into a kind of sacred space. This paradoxical empowerment-through-surrender is quintessentially Dickinsonian.

Conclusion

“I have no life but this” is a masterful distillation of Emily Dickinson’s poetic genius—her ability to convey vast emotional and philosophical landscapes within a few spare lines. Through paradox, negation, and metaphysical imagery, she explores themes of existential dependence, the redefinition of death, and the constrictive yet transcendent nature of love. Situating the poem within its historical, literary, and biographical contexts deepens our appreciation of its complexity, while its emotional immediacy ensures its timeless resonance.

Dickinson’s work continues to captivate because it speaks to the fundamental human condition—our search for meaning within the confines of our relationships, our mortality, and our own minds. In just eight lines, she captures the terrifying beauty of a life entirely bound to another, leaving readers to ponder: Is such absolute devotion liberation, or the most profound confinement of all?

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!