On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book

Charles Tennyson Turner

1808 to 1879

Some hand, that never meant to do thee hurt,

Has crush'd thee here between these pages pent;

But thou hast left thine own fair monument,

Thy wings gleam out and tell me what thou wert:

Oh! that the memories, which survive us here,

Where half as lovely as these wings of thine!

Pure relics of a blameless life, that shine

Now thou art gone. Our doom is ever near:

The peril is beside us day by day;

The book will close upon us, it may be,

Just as we lift ourselves to soar away

Upon the summer-airs. But, unlike thee,

The closing book may stop our vital breath,

Yet leave no lustre on our page of death.

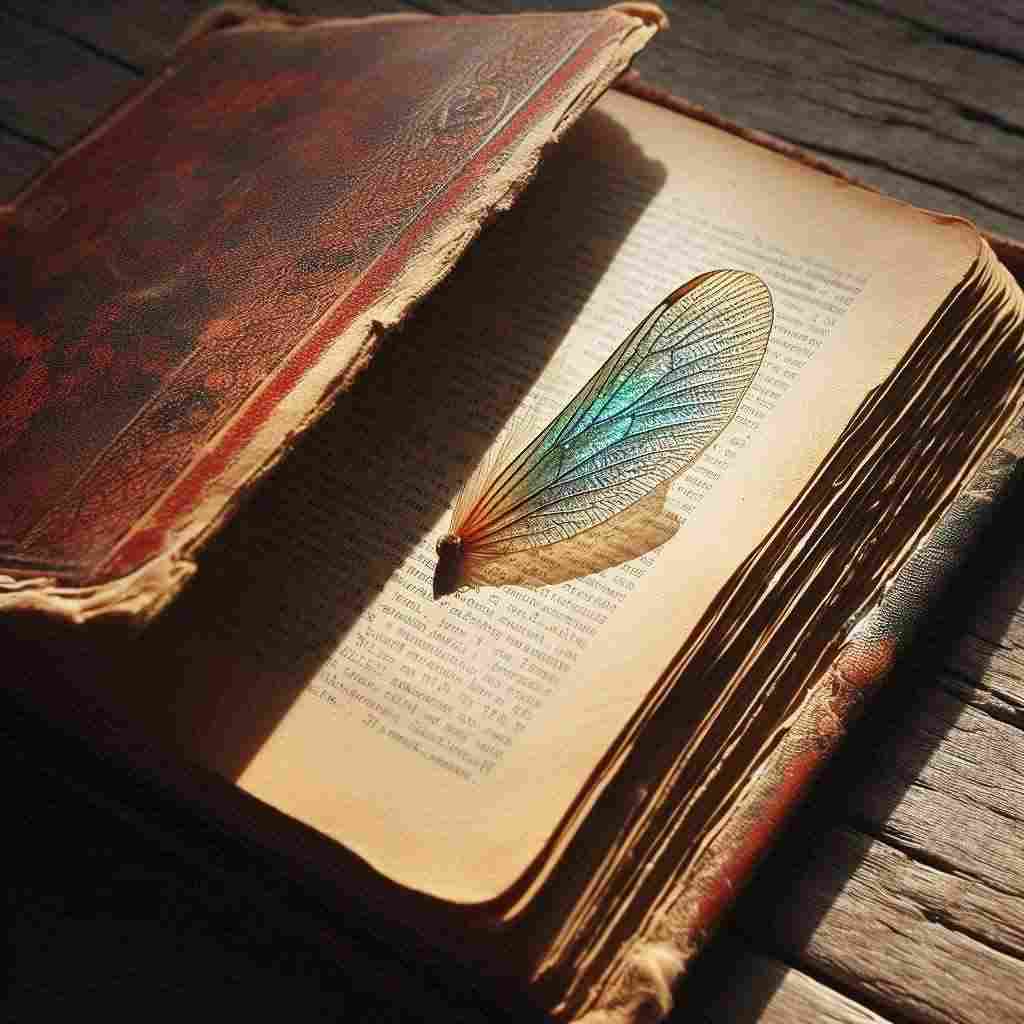

Charles Tennyson Turner's On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book

Introduction

Charles Tennyson Turner's sonnet "On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book" is a poignant meditation on mortality, legacy, and the fleeting nature of existence. This seemingly simple poem, inspired by the discovery of a crushed fly within the pages of a book, unfolds into a profound reflection on human life and death. Through careful analysis of its form, language, and thematic concerns, this essay will explore the depths of Turner's work and its place within the broader context of Victorian poetry.

Form and Structure

The poem adheres to the traditional Petrarchan sonnet form, consisting of an octave (the first eight lines) and a sestet (the final six lines). This structure is particularly apt for the subject matter, as it allows Turner to present a situation in the octave and then pivot to a more reflective, philosophical tone in the sestet.

The rhyme scheme (ABBAABBA CDCDCD) further reinforces this division, with the tightly interlocking rhymes of the octave giving way to the more open, contemplative structure of the sestet. This shift mirrors the poem's movement from the concrete (the crushed fly) to the abstract (musings on human mortality).

Imagery and Symbolism

Central to the poem is the image of the crushed fly, which serves as both a literal subject and a powerful symbol. The fly's delicate wings, preserved in death, become a metaphor for the lasting impact of a life well-lived. Turner writes:

Thy wings gleam out and tell me what thou wert:

Oh! that the memories, which survive us here,

Were half as lovely as these wings of thine!

This imagery is particularly striking in its juxtaposition of beauty and death. The gleaming wings, a remnant of life, stand in stark contrast to the fly's crushed body. This tension between the ephemeral nature of life and the potential for lasting beauty permeates the entire poem.

The book itself becomes a multifaceted symbol. On one level, it represents the arbitrary nature of death, crushing the fly "between these pages pent." On another, it symbolizes human knowledge and memory—the very means by which we might achieve a form of immortality. The closing of the book in the final lines thus takes on a dual significance, representing both death and the potential closure of our life's narrative.

Themes

Mortality and Legacy

The poem grapples extensively with the theme of mortality. The fly's sudden and accidental death serves as a reminder of the fragility of life and the omnipresence of mortality. Turner writes, "Our doom is ever near: / The peril is beside us day by day," emphasizing the constant proximity of death.

However, the poem is not simply a lament for life's brevity. It also explores the concept of legacy—what remains after we are gone. The fly's wings, beautiful even in death, prompt the speaker to reflect on human legacies:

Pure relics of a blameless life, that shine

Now thou art gone.

This line suggests that a life lived well can leave behind a lasting, beautiful impression, even after death.

The Randomness of Fate

The accidental nature of the fly's death—crushed by "Some hand, that never meant to do thee hurt"—underscores the theme of life's unpredictability. This randomness is further emphasized in the sestet, where the speaker imagines humans being cut off mid-flight, "Just as we lift ourselves to soar away / Upon the summer-airs."

Human Vanity and Insignificance

There's a subtle critique of human vanity in the poem. The speaker's wish that human memories could be "half as lovely" as the fly's wings suggests a recognition of our own insignificance. The final lines, lamenting that our deaths might "leave no lustre on our page of death," further emphasize this theme. In comparing human legacies unfavorably to that of a tiny insect, Turner challenges notions of human exceptionalism.

Language and Tone

Turner's language is characterized by its elegance and precision. The diction is elevated but not overwrought, befitting the serious subject matter. Phrases like "fair monument" and "Pure relics of a blameless life" lend a sense of dignity to the fly, elevating it as a subject worthy of contemplation.

The tone of the poem shifts subtly from the octave to the sestet. The octave, focused on describing the fly, maintains a tone of wonder and admiration. The sestet, however, takes on a more somber, reflective tone as it turns to human mortality. This shift is marked by the exclamation "Oh!" at the start of line 5, which serves as a turning point in the poem's emotional register.

Literary Context

"On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book" can be situated within the broader context of Victorian poetry, particularly that which deals with themes of mortality and nature. The poem's contemplative tone and focus on minutiae as a gateway to larger philosophical questions are reminiscent of the work of Gerard Manley Hopkins, while its structured form and elegiac quality echo elements of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poetry (Charles Tennyson Turner was, in fact, Alfred Tennyson's brother).

The poem also participates in the Victorian fascination with natural history and scientific observation. The detailed description of the fly's wings reflects the period's growing interest in entomology and other natural sciences. However, Turner uses this scientific observation as a springboard for metaphysical contemplation, blending empirical observation with spiritual and philosophical reflection in a manner characteristic of much Victorian poetry.

Conclusion

Charles Tennyson Turner's "On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book" is a masterful exploration of mortality, legacy, and the human condition, all sparked by an encounter with a tiny, crushed insect. Through its carefully constructed form, vivid imagery, and thoughtful contemplation, the poem invites readers to consider their own mortality and the marks they might leave behind.

The poem's enduring power lies in its ability to find profound meaning in the seemingly insignificant. By elevating the crushed fly to a subject of serious contemplation, Turner reminds us of the beauty and fragility inherent in all life. Moreover, by comparing human legacies unfavorably to the simple beauty of the fly's wings, the poem challenges us to consider what truly constitutes a life well-lived.

In its brief fourteen lines, "On Finding a Small Fly Crushed in a Book" encapsulates many of the preoccupations of Victorian poetry—the tension between science and spirituality, the search for meaning in a world increasingly explained by rational means, and the desire to find significance in the face of mortality. As such, it stands as a testament to the enduring power of poetry to illuminate the human condition, finding in the smallest of subjects the largest of truths.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!