The Man He Killed

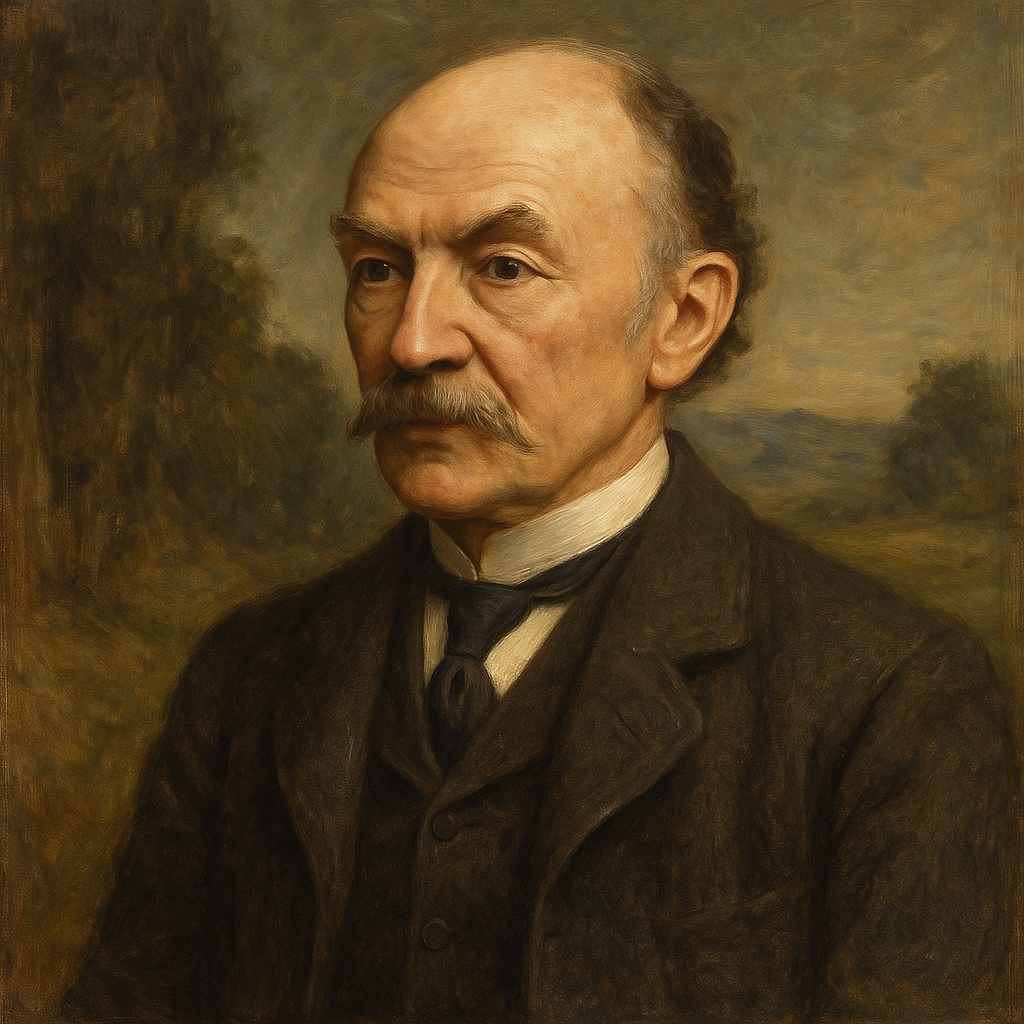

Thomas Hardy

1840 to 1928

"Had he and I but met

By some old ancient inn,

We should have sat us down to wet

Right many a nipperkin!

"But ranged as infantry,

And staring face to face,

I shot at him as he at me,

And killed him in his place.

"I shot him dead because —

Because he was my foe,

Just so: my foe of course he was;

That's clear enough; although

"He thought he'd 'list, perhaps,

Off-hand like — just as I —

Was out of work — had sold his traps —

No other reason why.

"Yes; quaint and curious war is!

You shoot a fellow down

You'd treat if met where any bar is,

Or help to half-a-crown."

Thomas Hardy's The Man He Killed

Introduction

Thomas Hardy's poem "The Man He Killed" stands as a poignant reflection on the absurdities of war and the arbitrary nature of enmity. Composed in the aftermath of the Second Boer War (1899-1902), this deceptively simple ballad encapsulates Hardy's characteristic blend of irony, pathos, and social commentary. Through its five quatrains, the poem presents a soldier's interior monologue as he grapples with the act of killing an enemy combatant, revealing the psychological and moral complexities that arise when societal constructs of warfare clash with innate human empathy.

Historical Context and Hardy's Anti-War Sentiment

To fully appreciate the nuances of "The Man He Killed," one must consider the historical backdrop against which Hardy penned these verses. The turn of the 20th century saw Britain embroiled in the Second Boer War, a conflict that drew significant criticism for its imperialistic motivations and the brutal tactics employed by British forces. Hardy, known for his skepticism towards societal institutions and his empathy for the common man, found in this war a potent subject for his anti-war sentiments.

The poem's setting, while not explicitly stated, evokes the atmosphere of this conflict. The mention of "infantry" and the casual tone of the narrator suggest a modern warfare scenario, distinct from the more romanticized battles of earlier eras. By grounding the poem in a contemporary context, Hardy makes its message immediate and relevant to his readers, many of whom would have had direct or indirect experiences with the ongoing war.

Structural Analysis and Poetic Technique

Hardy's choice of form for "The Man He Killed" is particularly noteworthy. The ballad structure, with its ABAB rhyme scheme and alternating iambic tetrameter and trimeter lines, lends the poem a song-like quality that belies its grave subject matter. This juxtaposition of form and content serves to heighten the sense of irony that permeates the work.

The use of colloquial language and dialect words like "nipperkin" and "'list" further reinforces the narrator's identity as an ordinary soldier, not a high-ranking officer or politician. This vernacular approach personalizes the narrative, making the speaker's moral dilemma more relatable and immediate to the reader.

Hardy's masterful use of enjambment, particularly evident in the transitions between stanzas, creates a sense of conversational flow that mimics the speaker's thought process. This technique allows Hardy to maintain the rigid structure of the ballad form while imbuing the poem with a natural, almost stream-of-consciousness quality that reflects the narrator's internal struggle.

Thematic Exploration: The Absurdity of War

At its core, "The Man He Killed" is an indictment of the arbitrary nature of warfare. The poem's central irony lies in the narrator's recognition that, under different circumstances, he and his victim could have been friends rather than foes. The opening stanza paints a vivid picture of camaraderie:

"Had he and I but met By some old ancient inn, We should have sat us down to wet Right many a nipperkin!"

This hypothetical scenario of shared drinks and companionship stands in stark contrast to the reality described in the second stanza, where the two men find themselves "ranged as infantry, / And staring face to face." The abrupt shift from potential friendship to mortal combat underscores the absurdity of their situation.

Hardy further emphasizes this theme through the narrator's struggle to justify his actions. The repetition of "Because" in the third stanza highlights the inadequacy of the explanation:

"I shot him dead because — Because he was my foe, Just so: my foe of course he was; That's clear enough; although"

The hesitation and circular reasoning reveal the speaker's discomfort with his own justification, suggesting that the labels of "friend" and "foe" are artificial constructs imposed by the machinery of war rather than inherent qualities of the individuals involved.

The Common Man in War

Another crucial theme that Hardy explores is the impact of war on ordinary individuals. The fourth stanza provides insight into the backgrounds of both the narrator and his victim:

"He thought he'd 'list, perhaps, Off-hand like — just as I — Was out of work — had sold his traps — No other reason why."

By suggesting that both men enlisted casually, possibly due to economic hardship, Hardy draws attention to the socioeconomic factors that often drive individuals into military service. This parallel between the narrator and his victim further underscores their fundamental similarity and the arbitrary nature of their antagonism.

The phrase "No other reason why" is particularly poignant, implying that neither man had a personal stake in the conflict or a deep-seated ideological motivation for fighting. Instead, they find themselves in opposing armies due to circumstance rather than conviction, a reality that adds to the overall sense of futility and waste that the poem conveys.

Irony and Cognitive Dissonance

The final stanza of the poem serves as a powerful culmination of its themes, encapsulating the cognitive dissonance experienced by the narrator:

"Yes; quaint and curious war is! You shoot a fellow down You'd treat if met where any bar is, Or help to half-a-crown."

The use of understatement in describing war as "quaint and curious" is deeply ironic, highlighting the disconnect between the brutal reality of combat and the speaker's attempt to rationalize his experience. The juxtaposition of killing a man and potentially sharing a drink with him or offering him financial assistance ("half-a-crown") in different circumstances serves to emphasize the arbitrary and absurd nature of wartime enmity.

This final stanza also reflects the narrator's attempt to distance himself from the emotional weight of his actions through casual language and generalization. The shift from "I" to "You" in this stanza suggests a desire to universalize the experience, perhaps as a coping mechanism for the speaker's guilt and moral uncertainty.

Conclusion

"The Man He Killed" stands as a testament to Thomas Hardy's ability to distill complex moral and philosophical questions into accessible, yet profound poetry. Through its exploration of the absurdities of war, the arbitrary nature of enmity, and the psychological toll of combat on ordinary individuals, the poem offers a timeless critique of warfare that resonates well beyond its immediate historical context.

Hardy's use of simple language and traditional form belies the complexity of the ideas he presents. By adopting the perspective of a common soldier, he humanizes the abstract concepts of war and enemy, forcing readers to confront the individual human cost of armed conflict. The poem's enduring power lies in its ability to evoke empathy and challenge the rationalization of violence, inviting readers to question the societal structures and ideologies that perpetuate warfare.

In an era where global conflicts continue to shape our world, "The Man He Killed" remains a poignant reminder of the common humanity that unites individuals across battle lines. It stands as a powerful anti-war statement, not through grandiose declarations or moral platitudes, but through the simple, haunting recognition of the shared experiences and fundamental similarities between those whom circumstance has deemed enemies.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!