Sursum Corda

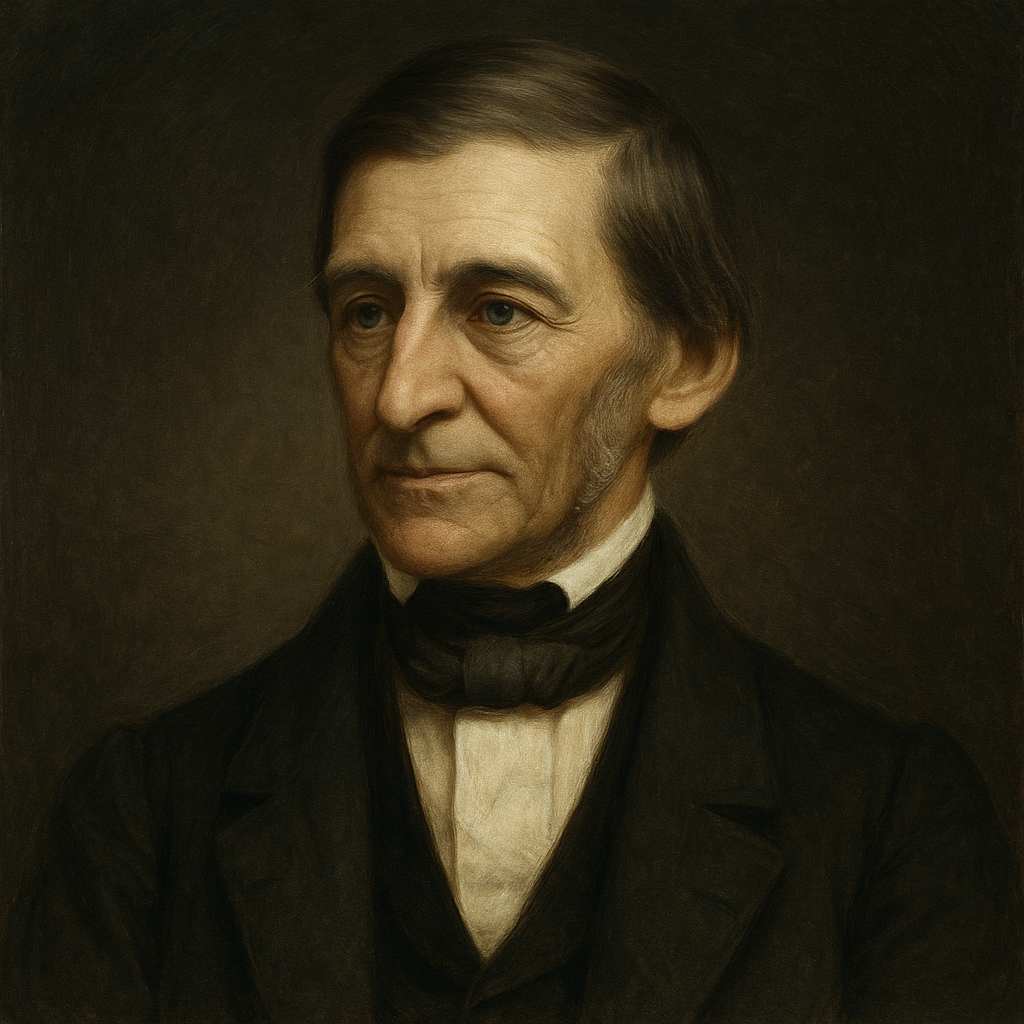

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803 to 1882

Seek not the spirit, if it hide

Inexorable to thy zeal:

Trembler, do not whine and chide:

Art thou not also real?

Stoop not then to poor excuse;

Turn on the accuser roundly; say,

'Here am I, here will I abide

Forever to myself soothfast;

Go thou, sweet Heaven, or at thy pleasure stay!'

Already Heaven with thee its lot has cast,

For only it can absolutely deal.

Ralph Waldo Emerson's Sursum Corda

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Sursum Corda (Latin for “Lift up your hearts”) is a compact yet profound meditation on self-reliance, spiritual autonomy, and the human relationship with the divine. Though brief, the poem encapsulates key tenets of Transcendentalist philosophy, a movement Emerson helped define, which emphasized intuition over doctrine, individualism over conformity, and a direct, unmediated connection with the spiritual realm. Through its assertive tone, paradoxical inversions of expectation, and philosophical depth, Sursum Corda challenges the reader to reconsider conventional notions of piety, humility, and the pursuit of truth.

Historical and Philosophical Context

To fully appreciate Sursum Corda, one must situate it within the broader framework of Emerson’s thought and the cultural milieu of mid-19th-century America. The poem was published in May-Day and Other Pieces (1867), a later collection that, while not as celebrated as Essays: First Series (1841) or Nature (1836), nevertheless reflects Emerson’s enduring preoccupations. By this time, Transcendentalism had already made its mark, advocating for a radical individualism that often put its adherents at odds with institutional religion and societal norms.

Emerson’s break with traditional Christianity—most dramatically signaled by his 1838 Divinity School Address, which criticized the church for its lifeless formalism—resonates in Sursum Corda. The poem’s opening lines, “Seek not the spirit, if it hide / Inexorable to thy zeal,” suggest that the divine cannot be apprehended through desperate seeking or dogged effort. This aligns with Transcendentalist belief in the immanence of the divine within nature and the self, rather than as a distant, external force to be supplicated.

Literary Devices and Structure

Despite its brevity, Sursum Corda employs a sophisticated interplay of rhetorical strategies. The poem is structured as a series of imperatives and declarations, creating a tone of confident exhortation. The speaker does not plead or question but commands: “Stoop not then to poor excuse; / Turn on the accuser roundly.” The absence of a traditional supplicatory posture—common in religious poetry—signals Emerson’s rejection of passive devotion in favor of self-assertion.

The poem’s central paradox lies in its inversion of traditional religious dynamics. Rather than the human soul yearning for God’s presence, Emerson suggests that “Already Heaven with thee its lot has cast.” In other words, divinity is not something to be sought externally but is already inherent within the self. This idea echoes Emerson’s famous assertion in Self-Reliance that “the relations of the soul to the divine spirit are so pure that it is profane to seek to interpose helps.”

Emerson’s diction is precise and weighted with philosophical significance. The phrase “Forever to myself soothfast” is particularly striking. “Soothfast” (an archaic term meaning “truthful” or “faithful”) suggests an unshakable commitment to one’s own inner truth, reinforcing the Transcendentalist ideal of authenticity. The speaker’s declaration “Here am I, here will I abide” evokes biblical language (cf. God’s self-identification as “I AM” in Exodus 3:14), subtly elevating the individual’s self-declaration to a sacred act.

Themes: Self-Reliance and Divine Immanence

The most prominent theme in Sursum Corda is the Emersonian doctrine of self-reliance, which posits that true wisdom and spiritual fulfillment come from within rather than from external authorities. The poem’s speaker does not beg for divine favor but instead asserts autonomy: “Go thou, sweet Heaven, or at thy pleasure stay!” This line is radical in its implication—the human will does not bend to Heaven’s whims; rather, Heaven’s presence is a given, and the individual retains agency.

Another key theme is the futility of forced spiritual striving. The opening lines warn against the “zeal” that seeks to extract truth from an “inexorable” spirit. This critique aligns with Emerson’s broader skepticism toward institutionalized religion, which he saw as stifling genuine spiritual experience. For Emerson, truth is not something to be extracted through laborious effort but recognized as already present.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

While Sursum Corda is philosophically dense, it is also deeply emotive. The poem’s tone shifts from admonishment (“Trembler, do not whine and chide”) to empowerment (“Here am I, here will I abide”), creating a psychological arc that mirrors the Transcendentalist journey from doubt to self-assurance. The speaker addresses a “Trembler,” likely symbolizing the anxious seeker who doubts their own spiritual worth. By the end, the poem reassures that Heaven has already “cast its lot” with the individual, eliminating the need for desperate seeking.

This emotional trajectory has a liberating effect, inviting the reader to shed self-doubt and embrace their inherent divinity. The poem’s brevity enhances its impact—each line carries weight, and the absence of superfluous language reinforces the message of essential truth.

Comparative Readings and Philosophical Underpinnings

Sursum Corda can be fruitfully compared to other Emersonian works, particularly The Over-Soul, which describes the divine as a universal spirit interfused with all beings. Both texts reject the notion of a hierarchical relationship between humanity and the divine, instead positing an organic unity.

The poem also resonates with Eastern philosophical traditions, particularly Advaita Vedanta, which teaches that the individual soul (atman) is one with the ultimate reality (Brahman). Emerson was influenced by Hindu scriptures, and Sursum Corda’s assertion that Heaven is already within the self parallels the Upanishadic declaration “Tat Tvam Asi” (“Thou art That”).

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Emerson’s Vision

Sursum Corda is a masterful distillation of Emerson’s core beliefs—self-trust, the divinity of the individual, and the rejection of hollow religiosity. Its power lies not only in its philosophical depth but in its ability to inspire. The poem does not merely describe a worldview; it enacts it, urging the reader to stand firm in their own truth.

In an age of increasing conformity and institutional dependency, Emerson’s message remains strikingly relevant. Sursum Corda challenges us to lift up our hearts—not in supplication, but in recognition of the sacred within. It is a call to spiritual courage, a reminder that the divine is not a distant reward but an ever-present reality, waiting only to be acknowledged.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!