The Ruined Maid

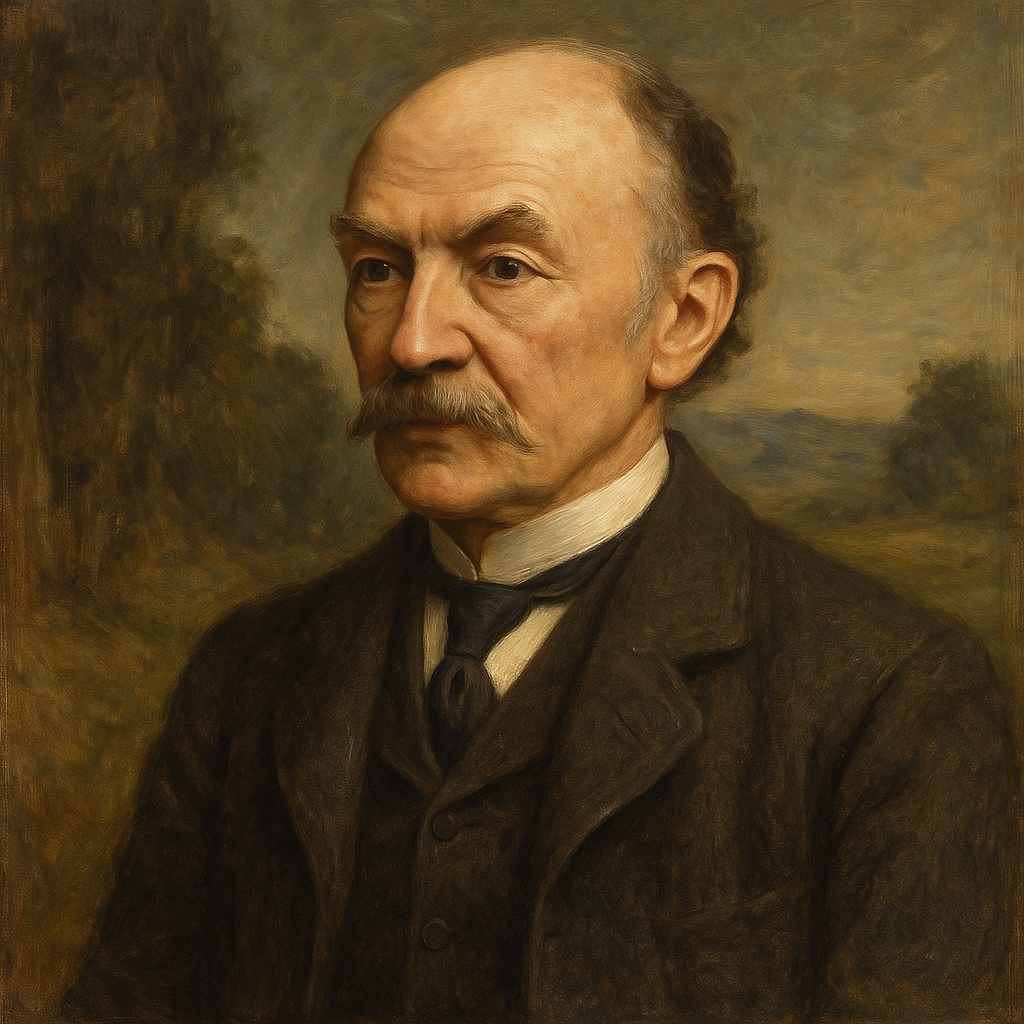

Thomas Hardy

1840 to 1928

"O 'Melia, my dear, this does everything crown!

Who could have supposed I should meet you in Town?

And whence such fair garments, such prosperi-ty?" —

"O didn't you know I'd been ruined?" said she.

— "You left us in tatters, without shoes or socks,

Tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks;

And now you've gay bracelets and bright feathers three!" —

"Yes: that's how we dress when we're ruined," said she.

— "At home in the barton you said thee' and thou,'

And thik oon,' and theäs oon,' and t'other'; but now

Your talking quite fits 'ee for high compa-ny!" —

"Some polish is gained with one's ruin," said she.

— "Your hands were like paws then, your face blue and bleak

But now I'm bewitched by your delicate cheek,

And your little gloves fit as on any la-dy!" —

"We never do work when we're ruined," said she.

— "You used to call home-life a hag-ridden dream,

And you'd sigh, and you'd sock; but at present you seem

To know not of megrims or melancho-ly!" —

"True. One's pretty lively when ruined," said she.

— "I wish I had feathers, a fine sweeping gown,

And a delicate face, and could strut about Town!" —

"My dear — a raw country girl, such as you be,

Cannot quite expect that. You ain't ruined," said she.

Thomas Hardy's The Ruined Maid

Thomas Hardy's poem presents a poignant encounter between two women, one of whom has undergone a dramatic transformation since leaving her rural home. The poem's structure, consisting of six stanzas of four lines each, creates a rhythmic dialogue that propels the narrative forward while revealing the complex social and moral implications of the speakers' divergent paths.

The poem opens with a chance meeting in town, where the narrator expresses surprise at encountering Melia, a former acquaintance from their shared rural background. The exclamatory tone of the opening lines conveys both excitement and bewilderment at Melia's altered appearance and apparent prosperity. Hardy's use of dialect and colloquial language, such as thee and thou, grounds the poem in a specific regional context while also highlighting the social distance that has grown between the two women.

As the conversation unfolds, it becomes clear that Melia's transformation is the result of her ruin - a euphemism for her fall into prostitution. The repetition of the phrase said she at the end of each stanza serves to emphasize Melia's voice and perspective, creating a haunting refrain that underscores the gravity of her situation. This repetition also contributes to the poem's ironic tone, as Melia's matter-of-fact responses contrast sharply with the narrator's naïve admiration of her newfound elegance.

Hardy employs vivid imagery to contrast the women's past and present circumstances. The description of their former life - in tatters, without shoes or socks, tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks - paints a picture of rural poverty and hard labor. In contrast, Melia's current appearance is characterized by gay bracelets and bright feathers, symbols of her newfound but morally compromised prosperity. This juxtaposition serves to highlight the harsh realities of rural life that may drive women to seek alternative means of survival.

The poem also explores themes of social mobility and the price of refinement. Melia's transformation extends beyond her physical appearance to encompass her speech and mannerisms. The narrator notes that Melia's talking quite fits 'ee for high company, suggesting that she has acquired the polish necessary to move in more elevated social circles. However, this refinement comes at a significant cost, as Melia repeatedly reminds us that it is gained with one's ruin.

Hardy's use of irony is particularly effective in the fifth stanza, where the narrator recalls Melia's former discontent with home-life, describing it as a hag-ridden dream accompanied by sighs and socks (likely a dialectal term for heavy sighs). The contrast between this past melancholy and Melia's current liveliness serves to underscore the complex nature of her transformation. While she may appear happier and more prosperous, the repeated reminder of her ruin suggests that this change comes with its own set of hardships and moral compromises.

The final stanza brings the poem's themes to a poignant conclusion. The narrator, seduced by the apparent glamour of Melia's new life, expresses a desire for feathers, a fine sweeping gown, and the ability to strut about Town. Melia's response - My dear - a raw country girl, such as you be, Cannot quite expect that. You ain't ruined - serves as both a warning and a reminder of the irreversible nature of her own transformation. The use of ain't in this final line reinforces the class distinction between the two women, while also suggesting that Melia has not entirely shed her rural origins despite her newfound refinement.

Throughout the poem, Hardy masterfully employs dialect and colloquial language to create a sense of authenticity and to highlight the social and cultural differences between the two women. The use of words like thik oon and theäs oon not only adds local color but also serves to emphasize the narrator's continued connection to her rural roots.

In conclusion, Hardy's poem offers a nuanced exploration of social mobility, rural poverty, and the often-hidden costs of urban sophistication. Through the contrasting experiences of the two women, the poem raises questions about the nature of progress and the sacrifices required to escape rural hardship. The ironic tone and subtle use of language create a complex portrait of a society in transition, where the promise of a better life often comes at a steep moral price.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!