The Chimney-Sweeper

William Blake

1757 to 1827

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry ‘Weep! weep! weep! weep!’

So your chimneys I sweep, and in soot I sleep.

There’s little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head,

That curled like a lamb’s back, was shaved; so I said,

‘Hush, Tom! never mind it, for, when your head’s bare,

You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair.’

And so he was quiet, and that very night,

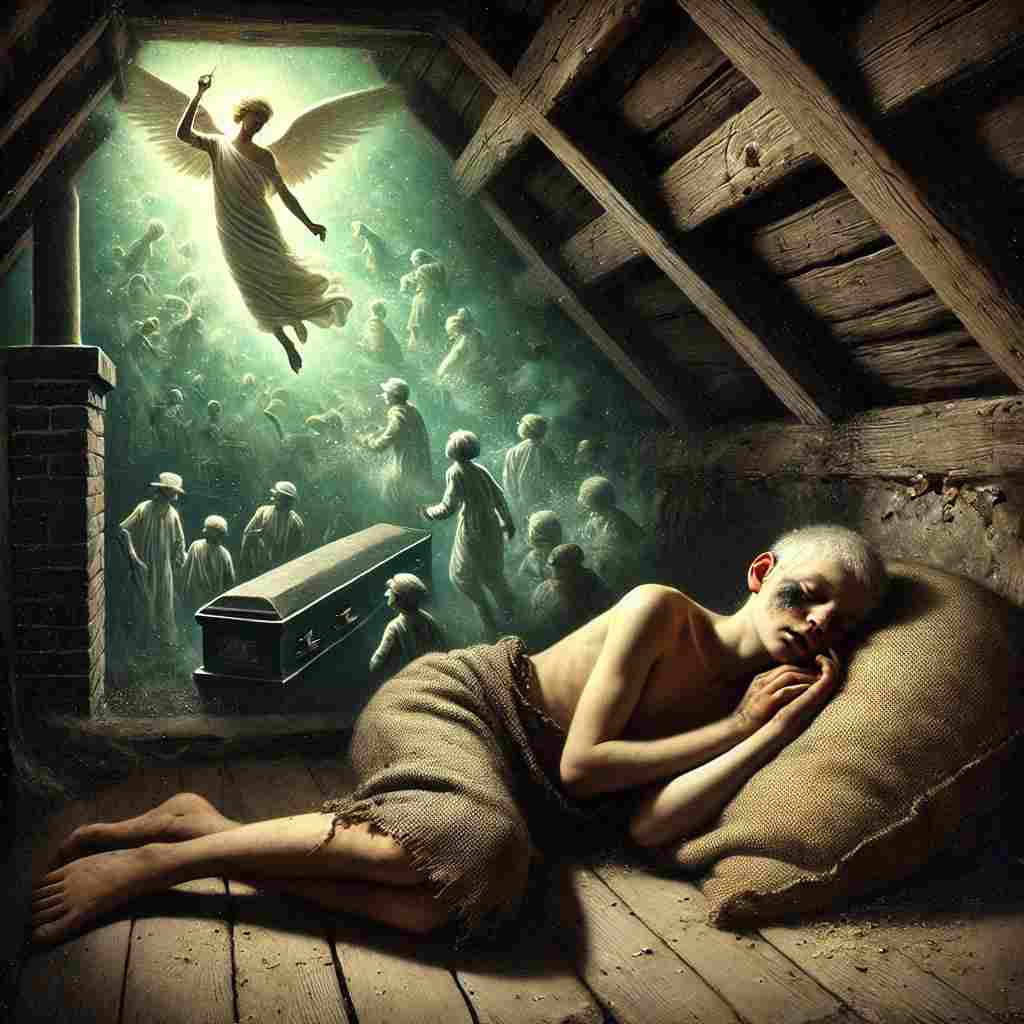

As Tom was a-sleeping, he had such a sight!—

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack,

Were all of them locked up in coffins of black.

And by came an angel, who had a bright key,

And he opened the coffins, and set them all free;

Then down a green plain, leaping, laughing, they run

And wash in a river, and shine in the sun.

Then naked and white, all their bags left behind,

They rise upon clouds, and sport in the wind:

And the angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy,

He’d have God for his father, and never want joy.

And so Tom awoke, and we rose in the dark,

And got with our bags and our brushes to work.

Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy and warm:

So, if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.

From Songs of Innocence

William Blake's The Chimney-Sweeper

William Blake’s The Chimney-Sweeper from Songs of Innocence is a poignant and deeply evocative poem that captures the harrowing realities of child labor in 18th-century England while simultaneously exploring themes of innocence, suffering, and redemption. Blake’s work is a masterful blend of simplicity and profundity, using the voice of a child to convey a narrative that is both heartbreaking and hopeful. This analysis will delve into the poem’s historical context, its use of literary devices, its thematic concerns, and its emotional resonance, offering a comprehensive understanding of its enduring significance.

Historical Context: The Plight of the Chimney Sweep

To fully appreciate The Chimney-Sweeper, it is essential to situate it within its historical context. The late 18th century, when Blake wrote this poem, was a period of rapid industrialization in England. Urban centers were expanding, and the demand for cheap labor was insatiable. Children, particularly those from impoverished families, were often sold into apprenticeships as chimney sweeps. These children, some as young as four or five, were forced to climb narrow, soot-filled chimneys, a task that was not only grueling but also deadly. Many suffered from respiratory diseases, burns, and deformities, and some even perished in the chimneys.

Blake’s poem reflects this grim reality. The opening lines, “When my mother died I was very young, / And my father sold me while yet my tongue / Could scarcely cry ‘Weep! weep! weep! weep!’” immediately establish the speaker’s vulnerability and the exploitation inherent in his situation. The repetition of “weep” echoes the child’s cry, but it also serves as a pun on “sweep,” highlighting the dual tragedy of lost innocence and forced labor. Blake’s choice to narrate the poem from the perspective of a child amplifies its emotional impact, as the reader is confronted with the stark contrast between the child’s innocence and the brutality of his circumstances.

Literary Devices: Simplicity and Symbolism

Blake’s use of literary devices in The Chimney-Sweeper is both subtle and powerful. The poem’s language is deceptively simple, mirroring the voice of a child, but this simplicity belies a rich tapestry of symbolism and imagery. One of the most striking aspects of the poem is its use of contrasting imagery to convey its themes. The soot and darkness of the chimney sweeps’ lives are juxtaposed with images of purity and light, such as Tom Dacre’s “white hair” and the angel’s “bright key.” These contrasts serve to underscore the poem’s central tension between innocence and corruption, suffering and redemption.

The dream sequence in the poem is particularly significant. When Tom Dacre dreams of thousands of sweepers “locked up in coffins of black,” the image is both literal and metaphorical. The coffins represent the physical and spiritual death of the children, trapped in their oppressive lives. However, the arrival of the angel, who “opened the coffins and set them all free,” introduces a note of hope. The children’s subsequent journey to a “green plain,” where they “wash in a river and shine in the sun,” symbolizes a return to innocence and a release from their suffering. This vision of liberation is deeply moving, but it is also tinged with irony, as the reader is aware that the children’s reality remains unchanged.

Blake’s use of religious imagery is also noteworthy. The angel’s promise that Tom will “have God for his father, and never want joy” if he is “a good boy” reflects the pervasive influence of Christianity in 18th-century England. However, this promise can be read as both comforting and subversive. On one level, it offers solace to the suffering children, suggesting that their hardships will be rewarded in the afterlife. On another level, it critiques the societal structures that exploit these children, implying that their suffering is justified by the promise of future happiness. This duality is characteristic of Blake’s work, which often challenges conventional religious and moral frameworks.

Themes: Innocence, Suffering, and Redemption

At its core, The Chimney-Sweeper is a meditation on the themes of innocence, suffering, and redemption. The poem’s portrayal of childhood innocence is both tender and tragic. The speaker’s description of Tom Dacre’s hair, which “curled like a lamb’s back,” evokes an image of purity and vulnerability. The shaving of Tom’s head, while practical for his work, is also a symbolic loss of innocence. Yet, the speaker’s reassurance that “the soot cannot spoil your white hair” suggests a resilience of spirit, a refusal to let external circumstances entirely corrupt the inner self.

The theme of suffering is pervasive throughout the poem. The children’s lives are marked by physical hardship, emotional deprivation, and social injustice. The image of the “coffins of black” is a powerful metaphor for their entrapment, both literal and figurative. However, Blake does not present suffering as an end in itself. Instead, he suggests that suffering can be transformative, leading to a form of redemption. The children’s dream of liberation and their ascent to a heavenly realm can be seen as a metaphor for spiritual transcendence, a release from the burdens of their earthly existence.

The theme of redemption is closely tied to the poem’s religious imagery. The angel’s promise of eternal joy if the children are “good” reflects a traditional Christian narrative of salvation. However, Blake’s treatment of this theme is complex. While the poem offers a vision of hope and redemption, it also raises questions about the nature of that redemption. Is it a genuine liberation, or is it a form of escapism that perpetuates the status quo? The final lines of the poem, “So, if all do their duty, they need not fear harm,” can be read as both a reassurance and a critique. On one hand, they suggest that moral integrity will be rewarded. On the other hand, they imply that the children’s suffering is a form of duty, a necessary sacrifice for their eventual salvation.

Emotional Impact: Pathos and Irony

One of the most striking aspects of The Chimney-Sweeper is its emotional impact. Blake’s use of a child narrator creates an immediate sense of pathos, as the reader is confronted with the stark contrast between the child’s innocence and the harshness of his reality. The poem’s simplicity and directness amplify its emotional resonance, allowing the reader to connect with the speaker’s plight on a deeply human level.

At the same time, the poem is infused with a sense of irony. The children’s dream of liberation is both hopeful and heartbreaking, as the reader is aware that their reality remains unchanged. The angel’s promise of eternal joy is similarly ambiguous, offering solace while also highlighting the injustice of the children’s suffering. This tension between hope and despair, innocence and corruption, gives the poem its emotional complexity and makes it a powerful commentary on the human condition.

Conclusion: A Timeless Critique of Injustice

In conclusion, William Blake’s The Chimney-Sweeper is a masterful exploration of the themes of innocence, suffering, and redemption. Through its use of simple yet powerful language, rich symbolism, and evocative imagery, the poem captures the harrowing realities of child labor in 18th-century England while also offering a vision of hope and liberation. Blake’s nuanced treatment of these themes, combined with his emotional sensitivity and moral urgency, makes The Chimney-Sweeper a timeless critique of social injustice and a profound meditation on the human spirit.

The poem’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to connect with readers on both an emotional and intellectual level. It challenges us to confront the injustices of our world while also reminding us of the resilience and dignity of the human spirit. In this way, The Chimney-Sweeper is not only a powerful work of art but also a call to action, urging us to strive for a world in which all children can experience the joy and freedom that Blake so eloquently envisions.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!