The Little Vagabond

William Blake

1757 to 1827

Dear mother, dear mother, the Church is cold;

But the Alehouse is healthy, and pleasant, and warm.

Besides, I can tell where I am used well;

Such usage in heaven will never do well.

But, if at the Church they would give us some ale,

And a pleasant fire our souls to regale,

We'd sing and we'd pray all the livelong day,

Nor ever once wish from the Church to stray.

Then the Parson might preach, and drink, and sing,

And we'd be as happy as birds in the spring;

And modest Dame Lurch, who is always at church,

Would not have bandy children, nor fasting, nor birch.

And God, like a father, rejoicing to see

His children as pleasant and happy as He,

Would have no more quarrel with the Devil or the barrel,

But kiss him, and give him both drink and apparel.

William Blake's The Little Vagabond

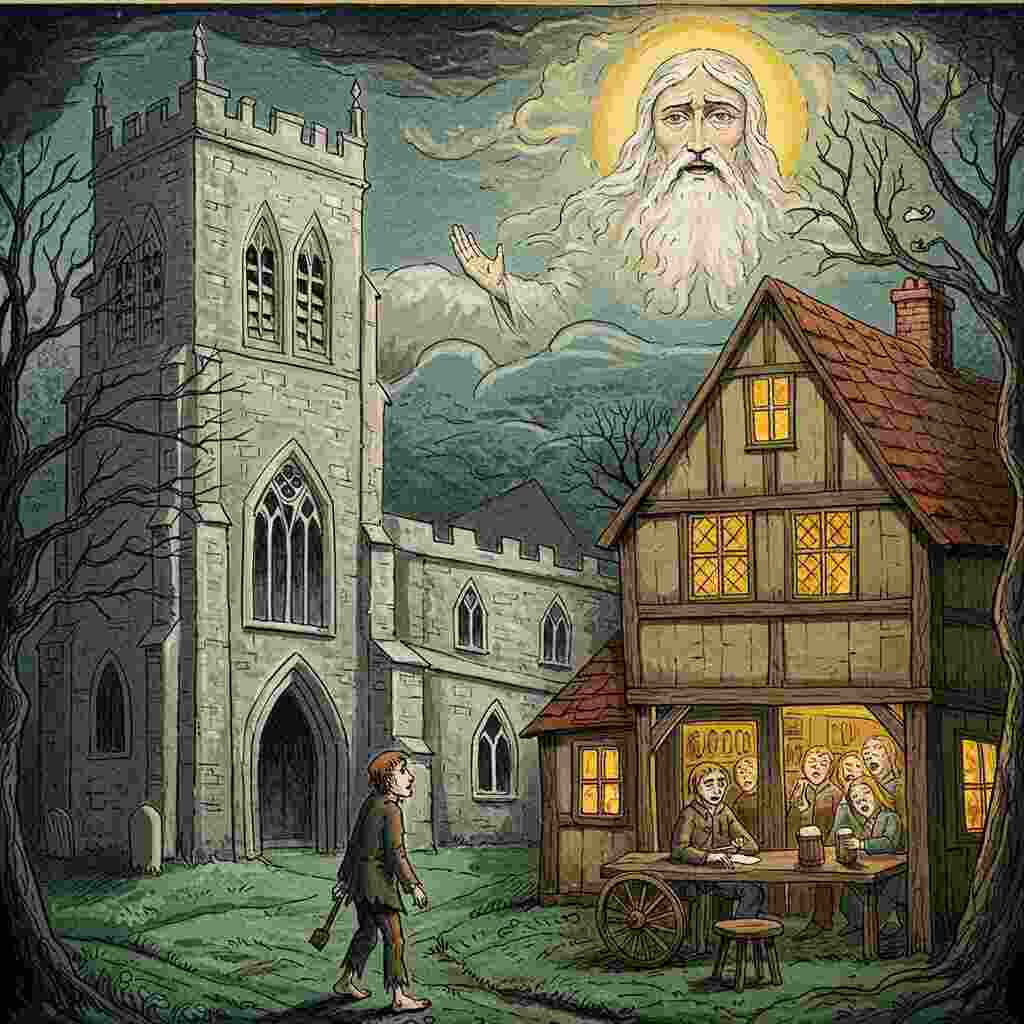

William Blake’s The Little Vagabond is a deceptively simple poem that encapsulates his lifelong rebellion against the oppressive structures of organized religion. Published in Songs of Experience (1794), the poem critiques the cold, joyless nature of the Church while advocating for a more humane, celebratory spirituality rooted in warmth, community, and pleasure. Through the voice of a child—a recurring figure in Blake’s work symbolizing innocence and unfiltered truth—the poem contrasts the rigid moralism of the Church with the conviviality of the alehouse, suggesting that true divinity resides in human happiness rather than in ascetic dogma.

This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance. Additionally, we will consider Blake’s broader philosophical and theological views, comparing The Little Vagabond to other works in his oeuvre to illuminate its significance within his radical vision of spiritual and social liberation.

Historical and Cultural Context: Blake’s Critique of 18th-Century Religion

To fully appreciate The Little Vagabond, we must situate it within the religious and social climate of late 18th-century England. The Church of England, as an institution, was deeply entwined with state power, enforcing moral discipline through sermons that emphasized sin, punishment, and obedience. Blake, a dissenter who rejected orthodox Christianity, saw the Church as complicit in the psychological and social repression of the poor.

The poem’s contrast between the "cold" Church and the "warm" alehouse reflects Blake’s belief that institutional religion had abandoned the true spirit of Christ—compassion, joy, and human fellowship—in favor of control. The alehouse, often condemned by religious moralists as a den of vice, is here reimagined as a site of genuine community, where the "vagabond" (a term connoting both social marginalization and freedom) finds acceptance. This inversion of moral expectations is characteristic of Blake’s subversive wit, challenging the reader to reconsider where divinity truly resides.

Moreover, the poem engages with Enlightenment debates about pleasure and virtue. Philosophers like Jeremy Bentham argued for utilitarianism—the greatest happiness for the greatest number—while religious authorities often framed pleasure as sinful. Blake’s poem aligns with more radical thinkers (such as Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft) who questioned institutional hypocrisy, suggesting that a loving God would prefer His children to be "happy as He" rather than suffering under punitive doctrines.

Literary Devices: Irony, Imagery, and the Voice of the Child

Blake employs several key literary devices to convey his critique with both sharpness and lyrical charm.

1. The Child’s Voice as a Vehicle for Truth

The poem is narrated by a child, a technique Blake frequently uses (as in The Chimney Sweeper and The Lamb) to underscore the corruption of adult institutions. The child’s plea—"Dear mother, dear mother"—imbues the poem with pathos, framing the Church’s austerity as a failure of nurture. The simplicity of the language belies its radical message: the speaker is not rejecting God but rather the Church’s joyless interpretation of Him.

2. Irony and Satire

Blake’s irony is evident in the suggestion that heaven’s "usage" (treatment) would "never do well" if it mirrored the Church’s coldness. The poem satirizes the idea that God desires human suffering, proposing instead that a truly divine order would embrace pleasure: "And God, like a father, rejoicing to see / His children as pleasant and happy as He." The image of God kissing the Devil and sharing drink dismantles the binary of good and evil, a recurring theme in Blake’s work (e.g., The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).

3. Contrastive Imagery

The poem’s power derives from its stark contrasts:

-

Cold vs. Warmth: The Church is "cold," while the alehouse is "pleasant, and warm." This dichotomy extends beyond physical comfort to emotional and spiritual fulfillment.

-

Restriction vs. Freedom: The Church is associated with "fasting" and "birch" (a rod used for corporal punishment), while the alehouse offers liberation in "sing[ing] and pray[ing] all the livelong day."

-

Hierarchy vs. Fellowship: The Parson’s preaching is juxtaposed with communal singing, suggesting that true worship should be participatory rather than authoritarian.

Themes: Joy as Sacred, the Hypocrisy of the Church, and Blake’s Vision of God

1. The Sanctity of Joy

Blake’s theology centers on the idea that "Energy is Eternal Delight" (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell). In The Little Vagabond, he posits that human happiness is not antithetical to holiness but essential to it. The speaker’s vision of a Church that provides "ale" and a "pleasant fire" redefines worship as an act of communal joy rather than solitary suffering.

2. Critique of Religious Hypocrisy

The poem exposes the Church’s failure to practice what it preaches. While the Parson might "drink, and sing," the congregation is denied such pleasures. The mention of "modest Dame Lurch," who is "always at church" yet has "bandy children" (a possible reference to malnutrition or neglect), underscores the disconnect between religious observance and genuine morality.

3. A Reconciled Universe

The closing lines present a startlingly inclusive vision: God reconciles with the Devil, ending their "quarrel." This reflects Blake’s belief that the division between good and evil is a false construct imposed by religious institutions. In his mythology, the Devil is often a figure of creative rebellion (as in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell), and here, the image of God offering "drink and apparel" suggests a universe where all beings are embraced.

Comparative Analysis: Blake’s Broader Work and Literary Influences

The Little Vagabond resonates with other Songs of Experience, particularly The Chimney Sweeper, where the Church’s complicity in child exploitation is condemned ("And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King / Who make up a heaven of our misery"). Both poems indict institutional religion for perpetuating suffering rather than alleviating it.

Comparatively, the poem’s tone is lighter than The Tyger or London, but its critique is no less incisive. It also echoes the themes of The Divine Image (from Songs of Innocence), which celebrates mercy, pity, and love as divine attributes—qualities the Church in The Little Vagabond lacks.

Philosophically, Blake’s vision aligns with Romanticism’s emphasis on individual feeling over institutional dogma. Like Rousseau, who argued that society corrupts natural goodness, Blake suggests that true spirituality is intuitive and joyous, not dictated by clerical authority.

Emotional Impact: Pathos and Subversive Humor

The poem’s emotional force lies in its blend of innocence and rebellion. The child’s voice evokes sympathy, making the Church’s indifference seem all the more cruel. Yet there is also humor in the absurdity of the proposal—what if the Church were as welcoming as an alehouse? This playful irony disarms the reader, making the underlying critique more potent.

The final image of God embracing the Devil is both shocking and liberating, challenging deep-seated moral binaries. For Blake, true divinity is not about judgment but about unity and delight—a vision as radical today as it was in the 18th century.

Conclusion: Blake’s Enduring Relevance

The Little Vagabond remains a powerful indictment of religious hypocrisy and a celebration of embodied joy. In an age where institutions often prioritize control over compassion, Blake’s poem is a reminder that spirituality should uplift rather than suppress the human spirit. His vision of a warm, ale-filled Church may be whimsical, but its underlying demand for a more loving and inclusive faith is profoundly serious.

Blake’s genius lies in his ability to convey revolutionary ideas through seemingly simple verse. The Little Vagabond is not just a critique of the Church; it is an invitation to reimagine divinity itself—as something alive, joyful, and radically kind.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!