A Little Boy Lost

William Blake

1757 to 1827

'Nought loves another as itself,

Nor venerates another so,

Nor is it possible to thought

A greater than itself to know.

'And, father, how can I love you

Or any of my brothers more?

I love you like the little bird

That picks up crumbs around the door.'

The Priest sat by and heard the child;

In trembling zeal he seized his hair,

He led him by his little coat,

And all admired his priestly care.

And standing on the altar high,

'Lo, what a fiend is here!' said he:

'One who sets reason up for judge

Of our most holy mystery.'

The weeping child could not be heard,

The weeping parents wept in vain:

They stripped him to his little shirt,

And bound him in an iron chain,

And burned him in a holy place

Where many had been burned before;

The weeping parents wept in vain.

Are such things done on Albion's shore?

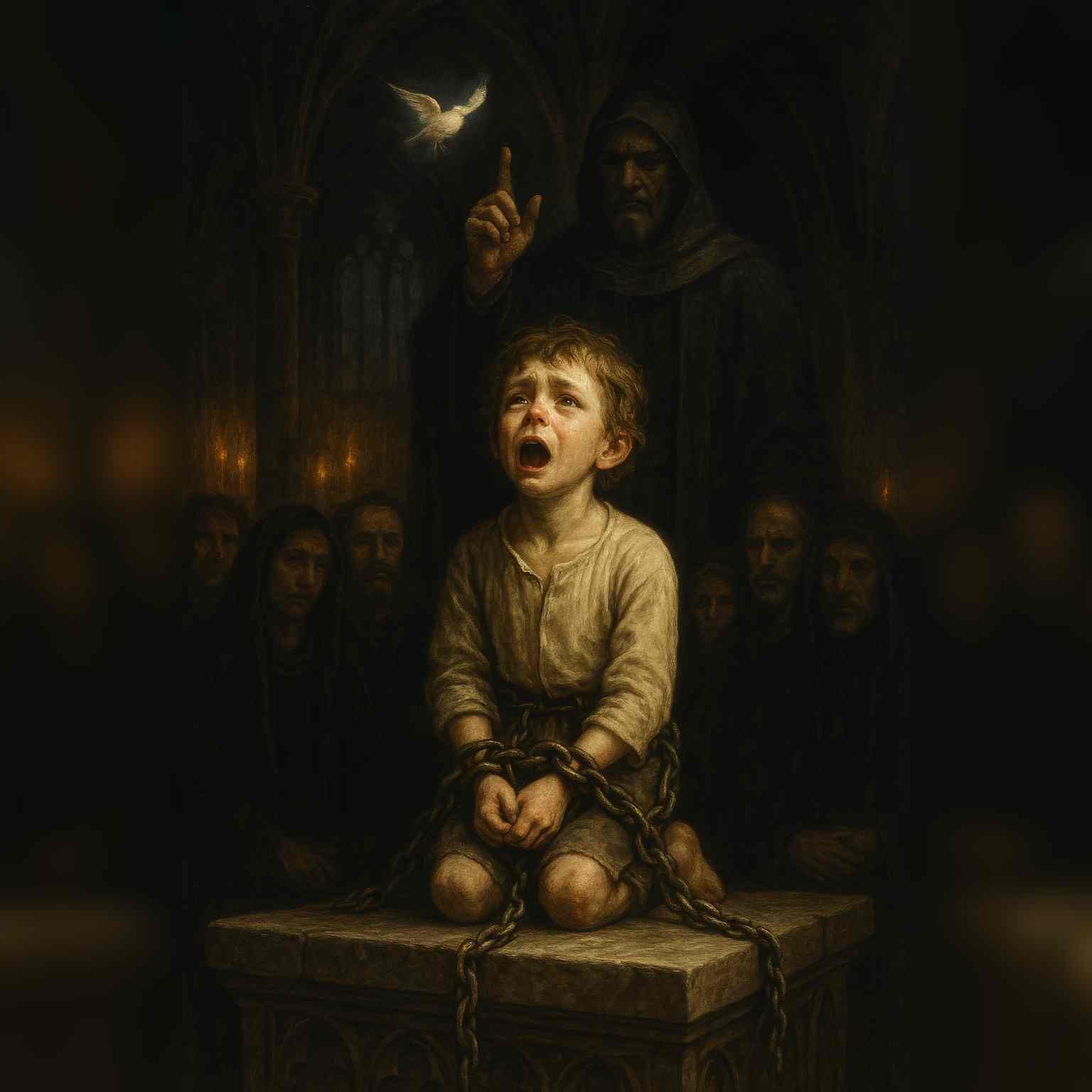

William Blake's A Little Boy Lost

William Blake’s A Little Boy Lost is a harrowing indictment of institutionalized religion, oppressive authority, and the suppression of innocence. Published in Songs of Experience (1794), the poem exemplifies Blake’s radical critique of the moral and religious hypocrisy of his time. Through stark imagery, irony, and emotional intensity, Blake exposes the cruelty of dogma and the tragic fate of those who dare to question it. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional impact, while also considering Blake’s philosophical and biographical influences.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate A Little Boy Lost, one must situate it within the late 18th-century milieu of political and religious upheaval. Blake lived during the Age of Enlightenment, a period that championed reason, individualism, and skepticism toward traditional authority. However, he also witnessed the violent backlash against such ideals—most notably in the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror (1793–94), where revolutionary fervor gave way to new forms of tyranny.

Blake’s England was no less repressive. The Church of England maintained significant power, and dissenting voices—whether Deists, radicals, or freethinkers—faced persecution. The poem’s reference to "Albion’s shore" (a poetic name for England) suggests that Blake saw his own country as complicit in such atrocities. The burning of the child echoes historical witch trials, heretic executions, and the brutal suppression of dissent, all of which Blake condemned.

Moreover, the poem critiques the perversion of religious zeal. The priest, rather than embodying compassion, becomes an agent of cruelty, twisting doctrine to justify violence. This aligns with Blake’s broader disdain for organized religion, which he saw as a tool of oppression rather than spiritual liberation.

Literary Devices and Structure

Blake employs a variety of literary techniques to amplify the poem’s emotional and ideological weight.

1. Irony and Satire

The poem’s title itself is ironic—the boy is not merely "lost" in a physical sense but is destroyed by the very institutions that claim to guide him. The priest’s "trembling zeal" and the admiration for his "priestly care" are bitterly satirical, exposing how religious authority masquerades as benevolence while enacting brutality.

2. Symbolism

-

The Little Bird: The boy’s comparison of his love to a bird that "picks up crumbs around the door" symbolizes natural, instinctive affection—unpretentious and unmediated by dogma. The bird, a recurring motif in Blake’s work, represents freedom and innocence, making its contrast with the priest’s tyranny all the more devastating.

-

The Iron Chain and Fire: These symbolize the oppressive mechanisms of institutional religion. Fire, often a purifying symbol in Christian tradition, is perverted into an instrument of punishment, evoking historical burnings of heretics.

3. Imagery and Sensory Impact

Blake’s imagery is visceral and haunting. The "weeping child" and "weeping parents" create a sense of helpless despair, while the physical violence—"seized his hair," "bound him in an iron chain," "burned him in a holy place"—renders the horror tangible. The altar, traditionally a site of sacred communion, becomes a place of execution, heightening the blasphemy of the act.

4. Dialogue and Voice

The boy’s innocent questioning ("And, father, how can I love you / Or any of my brothers more?") contrasts sharply with the priest’s fanatical condemnation ("Lo, what a fiend is here!"). The child’s voice, logical and sincere, is silenced, illustrating how reason is crushed by authoritarian irrationality.

Themes

1. The Corruption of Religious Authority

The priest embodies institutional religion’s capacity for cruelty. His condemnation of the boy for "set[ting] reason up for judge / Of our most holy mystery" reveals Blake’s critique of blind faith. The "holy mystery" is not something to be understood but enforced, and any attempt to question it is met with violence.

2. The Destruction of Innocence

The boy, like many of Blake’s child figures (e.g., The Chimney Sweeper), represents purity and unfiltered perception. His destruction underscores how societal structures—particularly religious and educational systems—corrupt and annihilate innocence. The parents’ futile weeping mirrors societal complicity; they mourn but do not (or cannot) intervene.

3. Reason vs. Dogma

The boy’s sin, in the priest’s eyes, is using reason to question love’s hierarchy. Blake, influenced by Enlightenment ideals, champions individual thought over imposed doctrine. The poem thus becomes a warning against the dangers of anti-intellectualism in religion.

4. Societal Complicity and Hypocrisy

The bystanders who "admired his priestly care" reflect societal endorsement of tyranny. Blake suggests that oppression persists not just because of active perpetrators but because of passive enablers. The final line—"Are such things done on Albion’s shore?"—implicates England in this cycle of violence.

Comparative Analysis

A Little Boy Lost resonates with other works in Songs of Experience, particularly The Chimney Sweeper and The Little Vagabond, which also depict children victimized by societal institutions. However, its closest parallel is A Little Girl Lost (also in Songs of Experience), where another innocent child is punished for natural behavior deemed sinful by authorities.

Beyond Blake’s oeuvre, the poem recalls the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac—except here, there is no divine intervention, only human cruelty. It also prefigures later critiques of religious hypocrisy, such as Dostoevsky’s The Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov, where the Church is portrayed as suppressing freedom in the name of control.

Biographical and Philosophical Influences

Blake’s own spiritual beliefs were heterodox. He rejected the punitive God of orthodox Christianity, instead embracing a visionary, imaginative faith. His concept of "mind-forg’d manacles" (London) applies here—the chains that bind the boy are ideological, not just physical.

Blake was also deeply influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg, whose theology emphasized inner divinity over external ritual. The priest’s actions represent the antithesis of this belief, showcasing how organized religion stifles true spirituality.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s power lies in its devastating simplicity. The boy’s voice, earnest and logical, makes his fate all the more tragic. The parents’ helplessness ("wept in vain") amplifies the horror, suggesting that even familial love is powerless against institutionalized violence.

The final question—"Are such things done on Albion’s shore?"—forces the reader to confront contemporary injustices. Blake does not offer resolution; instead, he leaves us with a challenge: to recognize and resist such cruelty in our own world.

Conclusion

A Little Boy Lost is a masterful fusion of lyrical simplicity and profound critique. Through its searing irony, vivid imagery, and emotional depth, Blake exposes the mechanisms of oppression disguised as piety. The poem remains disturbingly relevant, a reminder of how easily dogma can eclipse humanity. In an age where religious and ideological extremism still claims victims, Blake’s warning echoes across centuries: the true "fiend" is not the questioning mind but the unyielding hand that seeks to silence it.

Blake’s genius lies in his ability to distill vast philosophical and political concerns into the plight of a single child. In doing so, he ensures that the reader does not merely intellectualize injustice but feels its visceral weight. This is poetry as protest, as lament, and ultimately, as a call to awaken.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!