St. Maurice

Nora Hopper Chesson

1871 to 1906

I slept and entered in "the blissful place

Of the heart's heal, and deadly woundes' cure,"

Where Love is wingless found, and Faith is sure,

And men and maidens look in God His face.

There, where green leaves twine closely in a bower,

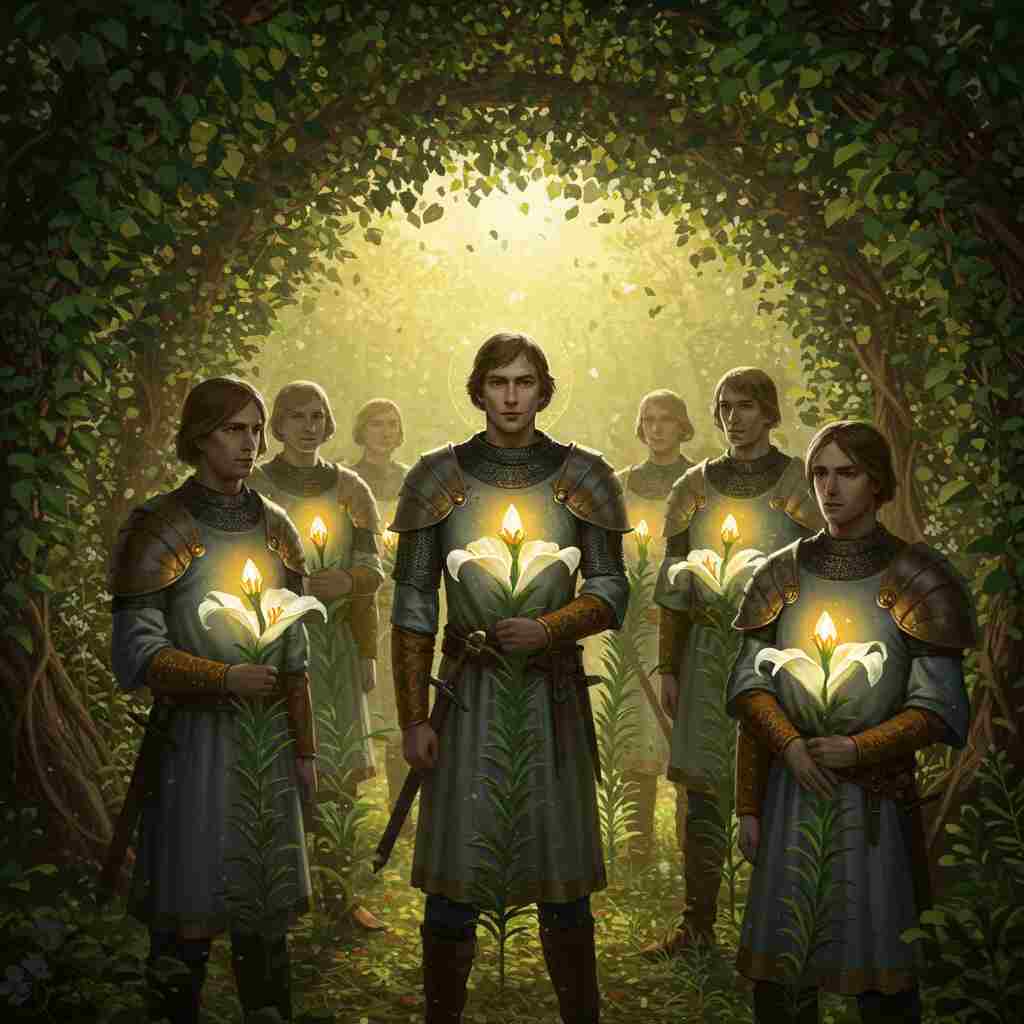

St. Maurice and his Theban men mount guard,

And on each breast I saw the martyr's sard

Burn in the white cup of a lily-flower.

O bold St. Maurice, is it good to rest

Here amid asphodels and lilies sown?

Or do you sometimes wish the old time back,

When you were tried with sword and fire and wrack,

Yet kept unhurt the bird within your breast,

Whose voice with peace has somewhat tuneless grown?

Nora Hopper Chesson's St. Maurice

Nora Hopper Chesson’s “St. Maurice” is a richly layered poem that invites readers into a liminal space where the spiritual and the earthly converge. Through its evocative imagery, historical allusions, and profound thematic concerns, the poem explores the tension between eternal rest and the vitality of earthly struggle. Chesson, an Irish poet of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was known for her engagement with Celtic mythology and Christian themes, and “St. Maurice” exemplifies her ability to weave these influences into a tapestry of profound emotional and spiritual resonance. This analysis will delve into the poem’s historical context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact, offering a comprehensive understanding of its significance.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate “St. Maurice,” it is essential to situate the poem within its historical and cultural milieu. The poem draws on the legend of Saint Maurice, a third-century Christian martyr who was the leader of the Theban Legion, a Roman military unit composed entirely of Christians. According to tradition, Maurice and his men were executed for refusing to renounce their faith and participate in pagan rituals. This act of martyrdom elevated Maurice to sainthood, and he became a symbol of unwavering faith and courage in the face of persecution.

Chesson’s poem reflects the Victorian fascination with medievalism and hagiography, a trend that sought to revive and romanticize the spiritual and chivalric ideals of the past. The Victorian era was marked by a profound interest in the intersection of faith, heroism, and martyrdom, as well as a longing for a purer, more transcendent form of spirituality. By invoking St. Maurice, Chesson taps into this cultural zeitgeist, using the saint’s story to explore broader questions about the nature of faith, sacrifice, and the human condition.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Chesson’s use of literary devices in “St. Maurice” is both intricate and purposeful, contributing to the poem’s depth and emotional resonance. The poem opens with a dreamlike vision, as the speaker describes entering “the blissful place / Of the heart’s heal, and deadly woundes’ cure.” This ethereal setting, characterized by its tranquility and divine presence, serves as a stark contrast to the earthly struggles that St. Maurice and his men endured. The imagery of “green leaves twine closely in a bower” evokes a sense of natural harmony and peace, while the mention of “the martyr’s sard / Burn in the white cup of a lily-flower” introduces a symbol of purity and sacrifice.

The lily, a traditional emblem of martyrdom and resurrection, is particularly significant in this context. Its whiteness suggests innocence and spiritual transcendence, while the “martyr’s sard” (a reference to the sardonyx stone, often associated with martyrdom) burning within it underscores the enduring legacy of Maurice’s sacrifice. This juxtaposition of natural beauty and spiritual symbolism creates a vivid tableau that invites readers to contemplate the interplay between the temporal and the eternal.

Chesson’s use of dialogue further enriches the poem’s texture. The speaker directly addresses St. Maurice, asking, “O bold St. Maurice, is it good to rest / Here amid asphodels and lilies sown?” This rhetorical question serves as a catalyst for reflection, prompting both the saint and the reader to consider the value of eternal peace versus the vitality of earthly struggle. The asphodel, a flower associated with the afterlife in Greek mythology, reinforces the poem’s exploration of themes related to death, memory, and transcendence.

Themes and Interpretations

At its core, “St. Maurice” grapples with the tension between the serenity of the afterlife and the dynamism of earthly existence. The poem’s central question—whether it is “good to rest” in the blissful realm of eternity—resonates with universal human concerns about the meaning of life, the nature of sacrifice, and the pursuit of spiritual fulfillment. St. Maurice’s martyrdom, which is both a historical fact and a metaphorical construct in the poem, serves as a lens through which these themes are examined.

One interpretation of the poem is that it critiques the passivity of eternal rest, suggesting that the true essence of faith and heroism lies in active struggle. The speaker’s question to St. Maurice—“Or do you sometimes wish the old time back, / When you were tried with sword and fire and wrack”—implies that the trials and tribulations of earthly life, though painful, are integral to the human experience. The “bird within your breast,” a metaphor for the soul or spirit, is described as having a voice that has “somewhat tuneless grown” in the afterlife, hinting at a loss of vitality or purpose in the absence of struggle.

This interpretation aligns with the Victorian preoccupation with the idea of “muscular Christianity,” which emphasized the importance of physical and moral strength in the practice of faith. By portraying St. Maurice as a figure who may long for the challenges of his past, Chesson underscores the idea that true heroism is not merely about enduring suffering but about embracing it as a means of spiritual growth.

Another theme that emerges in the poem is the tension between individual and collective identity. St. Maurice is depicted not as an isolated figure but as the leader of a community—“his Theban men”—who share in his martyrdom. This collective aspect of the saint’s story highlights the importance of solidarity and shared purpose in the face of adversity. The image of the Theban Legion mounting guard in the afterlife suggests that their sacrifice has created a lasting bond, one that transcends the boundaries of life and death.

Emotional Impact

The emotional impact of “St. Maurice” lies in its ability to evoke a sense of awe and introspection. The poem’s dreamlike quality, combined with its rich symbolism and historical resonance, creates a space for readers to reflect on their own beliefs and values. The speaker’s direct address to St. Maurice invites a personal connection, as though the reader is being drawn into a conversation with the saint himself. This sense of intimacy is heightened by the poem’s lyrical language and its exploration of universal themes such as faith, sacrifice, and the search for meaning.

The poem’s closing lines, in which the speaker questions whether St. Maurice’s voice has grown “tuneless” in the afterlife, are particularly poignant. This image of a muted or diminished spirit serves as a reminder of the complexity of human emotions and the potential for loss even in the midst of eternal peace. It challenges readers to consider what it means to live a meaningful life and whether true fulfillment can be found in rest or only in struggle.

Conclusion

Nora Hopper Chesson’s “St. Maurice” is a masterful exploration of faith, sacrifice, and the human condition. Through its evocative imagery, historical allusions, and profound thematic concerns, the poem invites readers to contemplate the tension between eternal rest and earthly struggle. By situating St. Maurice’s story within a dreamlike vision of the afterlife, Chesson creates a space for reflection on the nature of heroism, the value of community, and the enduring legacy of martyrdom.

The poem’s emotional impact lies in its ability to connect with readers on a deeply personal level, prompting them to consider their own beliefs and values. In doing so, “St. Maurice” exemplifies the power of poetry to transcend time and culture, offering insights that resonate across generations. Chesson’s work is a testament to the enduring relevance of spiritual and historical themes, as well as the capacity of poetry to illuminate the complexities of the human experience.

In conclusion, “St. Maurice” is not merely a poem about a saint; it is a meditation on the nature of faith, the meaning of sacrifice, and the eternal quest for spiritual fulfillment. Its rich imagery, historical depth, and emotional resonance make it a timeless piece of literature that continues to inspire and challenge readers today. Through this poem, Chesson invites us to ponder the ultimate questions of life and death, urging us to find meaning not only in the blissful peace of eternity but also in the struggles and triumphs of our earthly existence.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!