Faith

Ada Cambridge

1844 to 1926

And is the Great Cause lost beyond recall?

Have all the hopes of ages come to nought?

Is Life no more with noble meaning fraught?

Is Life but Death, and Love its funeral pall?

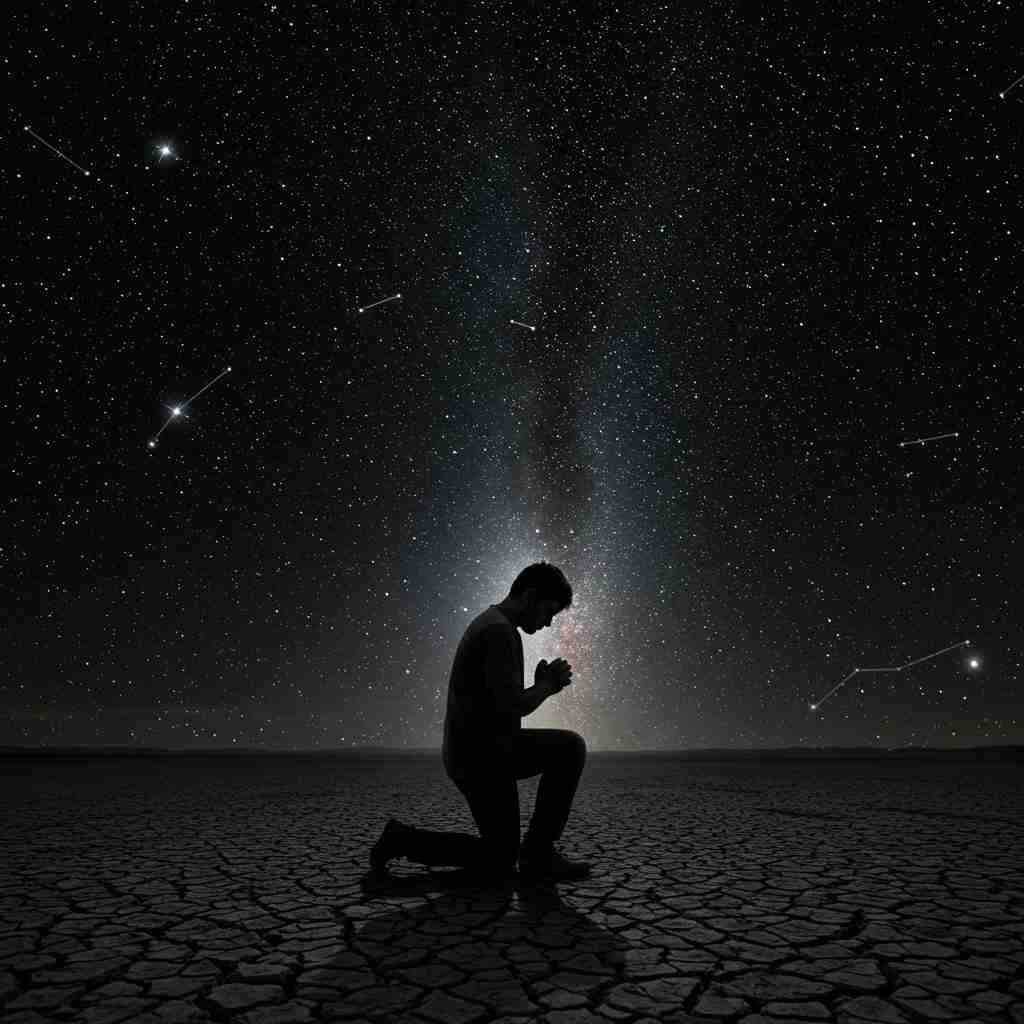

Maybe. But still on bended knees I fall,

Filled with a faith no preacher ever taught.

Oh God my God, by no false prophet wrought,

I believe still, in despite of it all!

Let go the myths and creeds of groping men.

This clay knows nought the Potter understands.

I own that Power divine beyond my ken,

And still can leave me in His shaping hands.

But, O my God, that madest me to feel!

Forgive the anguish of the turning wheel.

Ada Cambridge's Faith

The poem Faith by Ada Cambridge is a profound meditation on doubt, belief, and the human struggle to reconcile suffering with divine purpose. Written in the late 19th or early 20th century, it reflects the intellectual and spiritual turmoil of an era marked by rapid scientific advancement, religious skepticism, and the erosion of traditional faith. Cambridge, an English-Australian poet and novelist, was known for her exploration of religious and existential themes, often challenging conventional Victorian piety while maintaining a deep, if unorthodox, spiritual sensibility. This poem is no exception, as it grapples with the tension between despair and faith, human limitation and divine omnipotence, and the search for meaning in a seemingly indifferent universe.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate Faith, it is essential to situate it within its historical and cultural milieu. The late 19th century was a period of profound upheaval in religious thought. The rise of Darwinism, biblical criticism, and scientific materialism challenged long-held Christian beliefs, leading many to question the existence of a benevolent, omnipotent God. This crisis of faith was particularly acute in Victorian England, where the Church of England and traditional religious institutions were increasingly seen as inadequate to address the moral and existential dilemmas of the modern age. Cambridge, though deeply religious, was no stranger to these tensions. Her work often reflects a struggle to reconcile her faith with the intellectual currents of her time, and Faith is a poignant expression of this struggle.

The poem’s opening lines—“And is the Great Cause lost beyond recall? / Have all the hopes of ages come to nought?”—immediately evoke a sense of disillusionment and despair. The “Great Cause” can be interpreted as the Christian narrative of salvation, the Enlightenment ideal of progress, or even the broader human quest for meaning. The speaker’s questioning reflects the existential anxiety of an age in which traditional certainties were crumbling. Yet, even in the face of such doubt, the poem does not succumb to nihilism. Instead, it affirms a deeply personal, almost defiant faith—one that transcends dogma and institutional religion.

Themes and Emotional Impact

At its core, Faith is a poem about resilience in the face of doubt and suffering. The speaker’s faith is not the blind, unquestioning kind often associated with religious orthodoxy, but rather a hard-won, deeply personal conviction that persists “in despite of it all.” This theme of perseverance is underscored by the poem’s emotional intensity, which oscillates between despair and hope, anguish and acceptance. The speaker’s cry—“Oh God my God, by no false prophet wrought, / I believe still, in despite of it all!”—is both a plea and a declaration, capturing the raw vulnerability and fierce determination of one who clings to faith even when it seems irrational or futile.

The poem also explores the relationship between human suffering and divine will. The metaphor of the potter and the clay, drawn from biblical imagery (particularly Isaiah 64:8 and Romans 9:21), is central to this exploration. The speaker acknowledges their own ignorance and insignificance in the face of divine power—“This clay knows nought the Potter understands”—yet they also affirm their trust in that power, choosing to “leave me in His shaping hands.” This imagery suggests a surrender to a higher purpose, even as it raises difficult questions about the nature of that purpose. Why does the “turning wheel” of life cause such anguish? Is suffering merely a byproduct of divine craftsmanship, or does it serve some greater, inscrutable end? The poem does not provide easy answers, but it invites readers to wrestle with these questions alongside the speaker.

Literary Devices and Structure

Cambridge’s use of literary devices is both subtle and powerful, enhancing the poem’s emotional and thematic depth. The rhetorical questions that open the poem—“And is the Great Cause lost beyond recall? / Have all the hopes of ages come to nought?”—immediately draw the reader into the speaker’s inner turmoil. These questions are not merely intellectual exercises; they are cries of anguish, reflecting the speaker’s struggle to make sense of a world that seems devoid of meaning. The repetition of “Is Life” in the third and fourth lines reinforces this sense of existential despair, while the juxtaposition of “Life” and “Death” underscores the poem’s central tension between hope and hopelessness.

The poem’s language is richly evocative, blending biblical allusions with vivid, almost tactile imagery. The metaphor of the potter and the clay, for instance, is both visually and conceptually striking, evoking the image of a divine craftsman shaping human destiny. This metaphor is further developed in the final lines, where the speaker refers to “the turning wheel,” a phrase that suggests both the potter’s wheel and the cyclical nature of life and suffering. The use of enjambment in these lines—“But, O my God, that madest me to feel! / Forgive the anguish of the turning wheel”—creates a sense of fluidity and movement, mirroring the ongoing process of creation and transformation.

The poem’s tone is another key element of its power. While the speaker’s anguish is palpable, there is also a quiet dignity and resolve in their voice. This is particularly evident in the lines “Let go the myths and creeds of groping men. / This clay knows nought the Potter understands.” Here, the speaker rejects the “myths and creeds” of institutional religion in favor of a more personal, intuitive faith. The use of the word “groping” is especially telling, suggesting both the limitations of human understanding and the earnest, if imperfect, efforts of individuals to grasp the divine. The speaker’s humility—“I own that Power divine beyond my ken”—is balanced by a profound sense of trust and surrender, creating a tone that is both reverent and defiant.

Emotional and Philosophical Resonance

One of the most striking aspects of Faith is its ability to resonate with readers on both an emotional and philosophical level. The poem’s exploration of doubt and faith is deeply personal, yet it also speaks to universal human experiences. Who has not, at some point, questioned the meaning of life or the existence of a higher power? Who has not struggled to reconcile suffering with the idea of a benevolent God? Cambridge’s poem does not offer easy answers to these questions, but it provides a powerful expression of the human capacity for hope and resilience.

The poem’s emotional impact is heightened by its brevity and intensity. In just twelve lines, Cambridge captures the essence of a spiritual crisis and its resolution, moving from despair to affirmation with remarkable economy and precision. The final lines—“But, O my God, that madest me to feel! / Forgive the anguish of the turning wheel”—are particularly poignant, combining a plea for forgiveness with an acknowledgment of the divine purpose behind human suffering. The use of the word “feel” is significant, suggesting that the ability to experience emotion—even anguish—is a gift from God, a sign of our humanity and our connection to the divine.

Conclusion

Ada Cambridge’s Faith is a masterful exploration of doubt, belief, and the human condition. Written in a time of profound religious and intellectual upheaval, the poem reflects the struggles and aspirations of an age in which traditional certainties were being called into question. Yet, even in the face of such uncertainty, the poem affirms the possibility of faith—not as a blind adherence to dogma, but as a deeply personal, hard-won conviction that persists in the face of doubt and suffering.

Through its evocative imagery, rhetorical power, and emotional intensity, Faith invites readers to grapple with some of life’s most profound questions. What is the meaning of suffering? Is there a higher purpose to our lives? Can faith endure in the face of doubt? While the poem does not provide definitive answers to these questions, it offers a powerful testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring power of faith. In doing so, it reminds us of poetry’s unique ability to illuminate the complexities of the human experience and to connect us with something greater than ourselves.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!