Forgiven

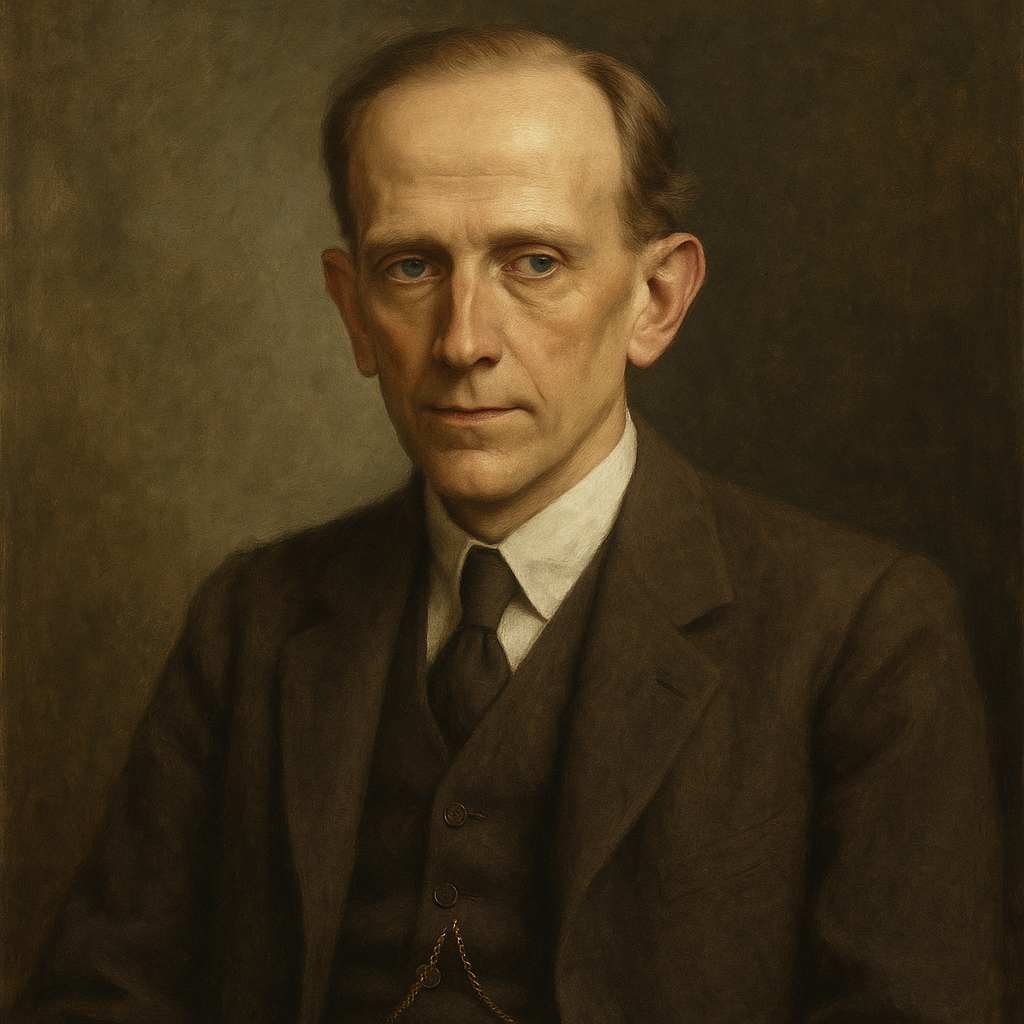

A. A. Milne

1882 to 1956

I found a little beetle; so that Beetle was his name,

And I called him Alexander and he answered just the same.

I put him in a match-box, and I kept him all the day...

And Nanny let my beetle out -

Yes, Nanny let my beetle out -

She went and let my beetle out -

And Beetle ran away.

She said she didn't mean it, and I never said she did,

She said she wanted matches and she just took off the lid,

She said that she was sorry, but it's difficult to catch

An excited sort of beetle you've mistaken for a match.

She said that she was sorry, and I really mustn't mind,

As there's lots and lots of beetles which she's certain we could find,

If we looked about the garden for the holes where beetles hid -

And we'd get another match-box and write BEETLE on the lid.

We went to all the places which a beetle might be near,

And we made the sort of noises which a beetle likes to hear,

And I saw a kind of something, and I gave a sort of shout:

"A beetle-house and Alexander Beetle coming out!"

It was Alexander Beetle I'm as certain as can be,

And he had a sort of look as if he thought it must be Me,

And he had a sort of look as if he thought he ought to say:

"I'm very very sorry that I tried to run away."

And Nanny's very sorry too for you-know-what-she-did,

And she's writing ALEXANDER very blackly on the lid,

So Nan and Me are friends, because it's difficult to catch

An excited Alexander you've mistaken for a match.

A. A. Milne's Forgiven

Introduction

A.A. Milne's poem "Forgiven" presents a deceptively simple narrative that, upon closer examination, reveals a complex interplay of themes including childhood innocence, the nature of forgiveness, and the power of imagination. This essay will delve into the multifaceted layers of Milne's work, exploring its linguistic features, structural elements, and thematic depth to uncover the sophisticated artistry beneath its childlike facade.

The Innocence of Childhood

At its core, "Forgiven" is a celebration of the innocent worldview of childhood. The narrator's attachment to a mere beetle, elevated to the status of a cherished pet with a proper name, exemplifies the child's capacity to find wonder and companionship in the most mundane aspects of nature. This theme is reinforced through Milne's use of simple, repetitive language that mimics a child's speech patterns, particularly evident in lines such as "Yes, Nanny let my beetle out - / She went and let my beetle out -". The repetition serves not only to emphasize the child's distress but also to capture the circular, insistent nature of a child's thought processes.

The naming of the beetle "Alexander" is particularly significant. By bestowing a human name upon an insect, the child demonstrates the anthropomorphic tendency common in early developmental stages. This act of naming transforms the beetle from a mere creature into a character in the child's personal narrative, imbuing it with perceived personality and importance far beyond its actual significance in the adult world.

The Complexity of Forgiveness

Despite its whimsical tone, the poem grapples with the weighty concept of forgiveness. The title itself, "Forgiven," immediately frames the narrative within this context, inviting the reader to consider the nature and process of forgiveness as it unfolds. The incident with Nanny accidentally releasing the beetle provides a microcosm for exploring how forgiveness operates, especially from a child's perspective.

Milne skillfully portrays the delicate dance of explanation, apology, and reconciliation between Nanny and the child. Nanny's repeated assertions that "she didn't mean it" and that "she was sorry" illustrate the adult attempt to make amends, while simultaneously highlighting the challenge of explaining unintentional harm to a child. The line "She said that she was sorry, but it's difficult to catch / An excited sort of beetle you've mistaken for a match" encapsulates this complexity, blending apology with practical explanation in a way that speaks to both child and adult sensibilities.

The resolution of this conflict is particularly nuanced. Rather than a straightforward acceptance of the apology, forgiveness is achieved through a shared activity - the search for a new beetle. This collaborative effort to rectify the situation serves as a powerful metaphor for the restorative nature of true forgiveness, emphasizing action over mere words.

The Power of Imagination

Throughout the poem, Milne showcases the transformative power of a child's imagination. The initial act of keeping a beetle in a match-box demonstrates the child's ability to create a world of play from ordinary objects. This theme is further developed in the latter part of the poem, where the search for a new beetle becomes an imaginative adventure.

The lines "We went to all the places which a beetle might be near, / And we made the sort of noises which a beetle likes to hear" beautifully capture the child's immersion in this imaginative realm. The use of the word "we" is particularly noteworthy, indicating that Nanny has been drawn into the child's world, participating in the fantasy as a means of making amends.

The climax of this imaginative journey occurs when the child believes they have found Alexander Beetle. Milne's use of anthropomorphism reaches its peak here, with the beetle ascribed human emotions and thought processes: "And he had a sort of look as if he thought it must be Me, / And he had a sort of look as if he thought he ought to say: / 'I'm very very sorry that I tried to run away.'" This projection of the child's own feelings onto the beetle serves a dual purpose - it resolves the narrative tension while also illustrating the child's developing capacity for empathy and understanding of complex emotions.

Linguistic and Structural Analysis

Milne's craftsmanship is evident in the poem's structure and linguistic choices. The AABB rhyme scheme and regular meter create a sing-song quality that echoes nursery rhymes, reinforcing the childlike perspective of the narrative. However, within this simple structure, Milne employs sophisticated techniques such as internal rhyme ("She said she didn't mean it, and I never said she did") and alliteration ("beetle-house and Alexander Beetle") to add depth and musicality to the verse.

The poem's structure also mirrors its thematic development. The first stanza, with its repeated lines about the beetle's escape, reflects the child's initial distress and fixation on the loss. As the poem progresses, the stanzas become more varied in their content, mirroring the emotional journey from upset to understanding and eventual reconciliation.

Milne's use of capitalization is also significant. The capitalization of "Beetle" throughout the poem elevates its status, reinforcing its importance in the child's world. The final stanza's emphasis on "ALEXANDER very blackly on the lid" serves as a visual representation of the resolution, with the beetle's full name restored and emphasized, symbolizing the restoration of order in the child's world.

Societal and Psychological Implications

Beyond its surface narrative, "Forgiven" offers insights into broader societal and psychological themes. The relationship between the child and Nanny reflects societal structures of care and authority. Nanny's role as both the source of distress and the facilitator of resolution speaks to the complex dynamics of adult-child relationships and the responsibility of caregivers in shaping a child's emotional development.

The poem also touches on themes of loss, restoration, and the malleability of truth in a child's mind. The possibility that the found beetle might not actually be Alexander, but is accepted as such, raises questions about the nature of truth and perception in childhood. This ambiguity allows for a reading of the poem as an exploration of how children construct and maintain their understanding of the world, even in the face of contradictory evidence.

Conclusion

A.A. Milne's "Forgiven" is a masterful blend of simplicity and complexity, offering a rich tapestry of themes woven into a seemingly straightforward children's poem. Through its exploration of childhood innocence, the intricacies of forgiveness, and the power of imagination, the poem provides a nuanced portrayal of a child's emotional and cognitive world.

Milne's linguistic dexterity and structural craftsmanship elevate the work beyond mere whimsy, creating a piece that resonates on multiple levels. The poem serves not only as a charming narrative but also as a meditation on the nature of relationships, the process of emotional growth, and the ways in which we construct meaning from our experiences.

In its entirety, "Forgiven" stands as a testament to Milne's ability to distill complex human experiences into accessible, yet profoundly meaningful verse. It invites readers, regardless of age, to reconnect with the wonder, imagination, and emotional honesty of childhood, while simultaneously offering insights into the deeper currents of human psychology and social interaction. As such, it remains a rich text for literary analysis, psychological study, and personal reflection, cementing Milne's place not just as a beloved children's author, but as a keen observer and articulator of the human condition.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!