If I die solvent

Edna St. Vincent Millay

1892 to 1950

If I die solvent—die, that is to say,

In full possession of my critical mind,

Not having cast, to keep the wolves at bay

In this dark wood—till all be flung behind—

Wit, courage, honour, pride, oblivion

Of the red eyeball and the yellow tooth;

Nor sweat nor howl nor break into a run

When loping Death’s upon me in hot sooth;

’Twill be that in my honoured hands I bear

What’s under no condition to be spilled

Till my blood spills and hardens in the air:

An earthen grail, a humble vessel filled

To its low brim with water from that brink

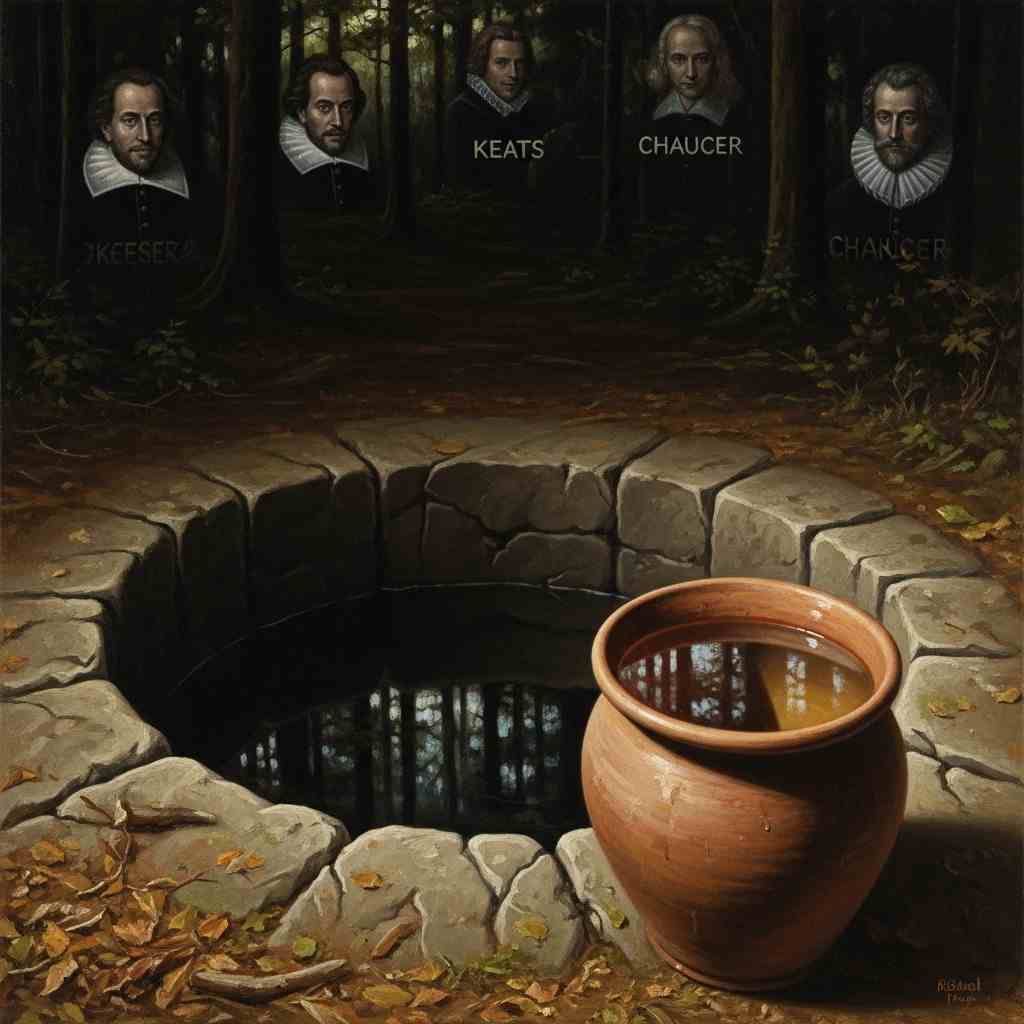

Where Shakespeare, Keats and Chaucer learned to drink.

Edna St. Vincent Millay's If I die solvent

Edna St. Vincent Millay’s If I Die Solvent is a compact yet profound meditation on artistic integrity, mortality, and the sacred duty of the poet. Written in Millay’s characteristically precise and evocative style, the poem grapples with the tension between worldly survival and poetic legacy, using striking imagery and allusions to position the speaker within a grand literary tradition. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its deployment of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance, while also considering Millay’s biography and the philosophical implications of her work.

Historical and Cultural Context

Millay wrote during the early 20th century, a period marked by both the lingering influence of Romanticism and the rise of Modernism. Her work often straddles these two movements, blending lyrical intensity with sharp, intellectual rigor. If I Die Solvent reflects this duality: it is deeply personal yet universal, traditional in form but modern in its existential concerns.

The poem’s title plays on the word solvent, which typically means financially sound but here takes on a metaphorical meaning—dying with one’s faculties intact, unbroken by the degradations of time. This concern with mental and artistic preservation was particularly resonant in the aftermath of World War I, when many artists and intellectuals grappled with disillusionment and the fragility of human dignity. Millay, who came of age during the war and was associated with the bohemian Greenwich Village scene, was acutely aware of how easily creativity could be crushed by external pressures.

Additionally, the poem engages with the long-standing literary trope of the poet’s sacred vocation. The reference to an "earthen grail" evokes Arthurian legend, suggesting that the poet’s role is quasi-religious—a guardian of truth and beauty. This aligns with the Romantic notion of the poet as a visionary, but Millay tempers it with humility, emphasizing the "humble vessel" rather than grandiosity.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Millay’s mastery of imagery and metaphor is on full display in If I Die Solvent. The poem opens with a conditional statement—"If I die solvent"—immediately establishing a tone of contingency. The speaker’s definition of "solvent" is clarified as dying "in full possession of my critical mind," suggesting that the true measure of a life well-lived is intellectual and artistic coherence, not mere material stability.

The extended metaphor of "the wolves" and "this dark wood" conjures Dante’s Inferno, positioning the speaker as a wanderer in a perilous existential landscape. The wolves symbolize the forces that threaten artistic purity—perhaps commercial pressures, societal expectations, or the erosion of one’s ideals under duress. The speaker resists casting away "Wit, courage, honour, pride" to survive, implying that such compromises would be a spiritual death before the physical one.

The visceral imagery of "the red eyeball and the yellow tooth" evokes decay and predation, reinforcing the poem’s preoccupation with mortality. Yet the speaker refuses to "sweat nor howl nor break into a run"—a defiant stance against fear. This echoes Stoic philosophy, particularly the idea that dignity lies in facing death with composure.

The most striking metaphor arrives in the final tercet: the "earthen grail" filled with water from the brink where "Shakespeare, Keats and Chaucer learned to drink." This transforms the poem into a meditation on literary inheritance. The grail, traditionally a symbol of divine grace, is here made "earthen" and "humble," suggesting that poetic inspiration is both sacred and accessible. The allusion to Shakespeare, Keats, and Chaucer places Millay within their lineage, asserting that true poetry is drawn from the same eternal wellspring.

Themes: Art, Mortality, and Legacy

At its core, If I Die Solvent is about what it means to live—and die—as an artist. The poem interrogates the compromises one might make to survive, both financially and psychologically, and posits that true artistic integrity requires resistance to such bargains. The speaker’s ideal death—"solvent" in mind and spirit—is one in which she has preserved her creative essence.

This theme resonates with Millay’s own life. Known for her fierce independence and bohemian lifestyle, she struggled with financial instability even as she achieved fame. Her insistence on artistic autonomy often put her at odds with publishers and critics. The poem can thus be read as a personal credo: a declaration that the poet’s duty is to safeguard their vision, even at great cost.

Another key theme is the relationship between the individual poet and literary tradition. The "earthen grail" suggests that poetry is a sacred trust, passed down through generations. By invoking Shakespeare, Keats, and Chaucer, Millay situates herself within a continuum of poets who have drawn from the same source of inspiration. This aligns with T.S. Eliot’s notion of the "historical sense" in Tradition and the Individual Talent—the idea that every new work exists in dialogue with the past.

Finally, the poem grapples with mortality not as an abstraction but as an imminent reality. The speaker does not romanticize death; instead, she confronts it with clear-eyed resolve. The image of blood "spill[ing] and harden[ing] in the air" is stark and visceral, underscoring the physicality of death even as the poem elevates the spiritual endurance of art.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Underpinnings

Despite its brevity, If I Die Solvent carries immense emotional weight. The speaker’s defiance in the face of death ("Nor sweat nor howl nor break into a run") is stirring, evoking the classical ideal of facing fate with courage. Yet there is also vulnerability in the admission that the "wolves" are ever-present, threatening to dismantle one’s principles.

The poem’s closing lines are its most transcendent. The image of the "earthen grail" is both humble and majestic, suggesting that the poet’s work is a sacred offering. The reference to Shakespeare, Keats, and Chaucer lends the poem a sense of timelessness, as if the speaker is taking her place in an unbroken chain of poetic voices. This creates a profound emotional resonance, blending personal resolve with collective artistic heritage.

Philosophically, the poem engages with existential questions: What does it mean to live authentically? How does one face mortality without succumbing to fear or compromise? Millay’s answer is that integrity—artistic and moral—is the only true measure of a life. The "water" from which the great poets drank is not merely inspiration but a symbol of truth itself, something that must be preserved and passed on.

Comparative Analysis and Conclusion

Millay’s poem invites comparison with other works that grapple with art and mortality. Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale, for instance, similarly juxtaposes the ephemeral nature of life with the endurance of art. However, where Keats laments his own mortality, Millay asserts a defiant continuity with the poets of the past.

Another apt comparison is W.B. Yeats’ Sailing to Byzantium, which also contrasts physical decay with artistic permanence. Yet Millay’s vision is less ornate, more grounded in the "earthen" and the "humble." Her grail is not golden but clay, emphasizing the poet’s role as a custodian rather than a solitary genius.

In conclusion, If I Die Solvent is a masterful exploration of artistic integrity, mortality, and literary tradition. Through its rich imagery, allusive depth, and emotional intensity, the poem asserts that true poetic greatness lies not in fame or wealth but in the unbroken transmission of creative truth. Millay’s voice is both personal and universal, a testament to the enduring power of poetry to confront life’s deepest questions. In an age where art is often commodified and compromised, her words remain a clarion call for authenticity—a reminder that the poet’s grail, however humble, is worth protecting unto death.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!