And they Obey

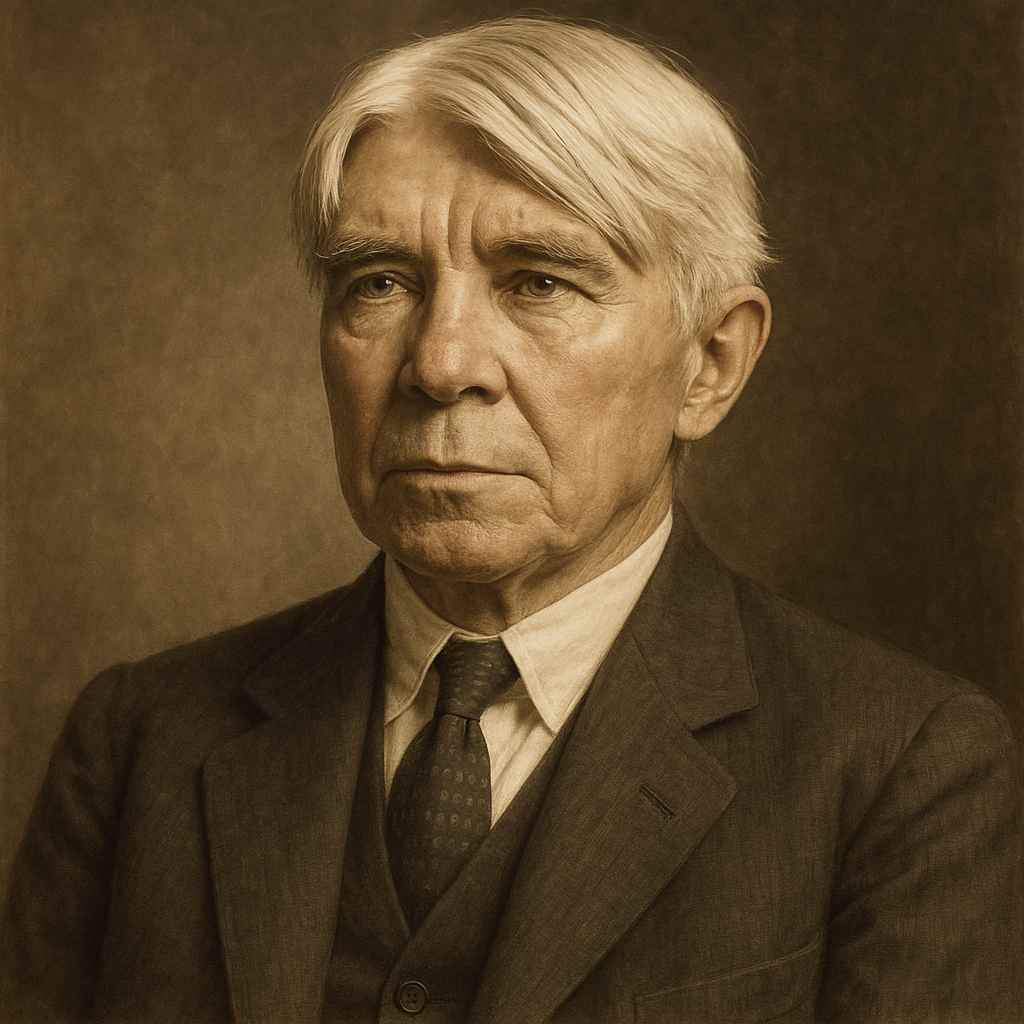

Carl Sandburg

1878 to 1967

Smash down the cities

Knock the walls to pieces

Break the factories and cathedrals, warehouses and homes

Into loose piles of stone and lumber and black burnt wood

You are the soldiers and we command you

Build up the cities.

Set up the walls again

Put together once more the factories and cathedrals, warehouses and homes

Into buildings for life and labor:

You are workmen and citizens all

We command you.

Carl Sandburg's And they Obey

Carl Sandburg’s "And they Obey" is a deceptively simple yet deeply resonant poem that encapsulates the cyclical nature of destruction and reconstruction, authority and submission, war and peace. Written during a period of immense social and political upheaval—Sandburg’s career spanned both World Wars, the Great Depression, and the rise of industrial capitalism—the poem reflects the tension between human agency and the forces that command it. Through stark imagery, imperative language, and a binary structure, Sandburg interrogates the dynamics of power, labor, and societal transformation. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional impact, while also considering philosophical and comparative perspectives.

Historical and Cultural Context

Sandburg (1878–1967) was a poet deeply embedded in the American experience, chronicling the lives of workers, soldiers, and ordinary citizens in his expansive body of work. A socialist sympathizer and a journalist, he was attuned to the struggles of the laboring class and the destructive capacities of industrialization and war. "And they Obey" can be read as a response to the mechanized violence of World War I (1914–1918), during which cities were reduced to rubble and then hastily rebuilt in the aftermath. The poem’s publication date is unclear, but its themes align with Sandburg’s post-war writings, where he often grappled with the paradoxes of progress and ruin.

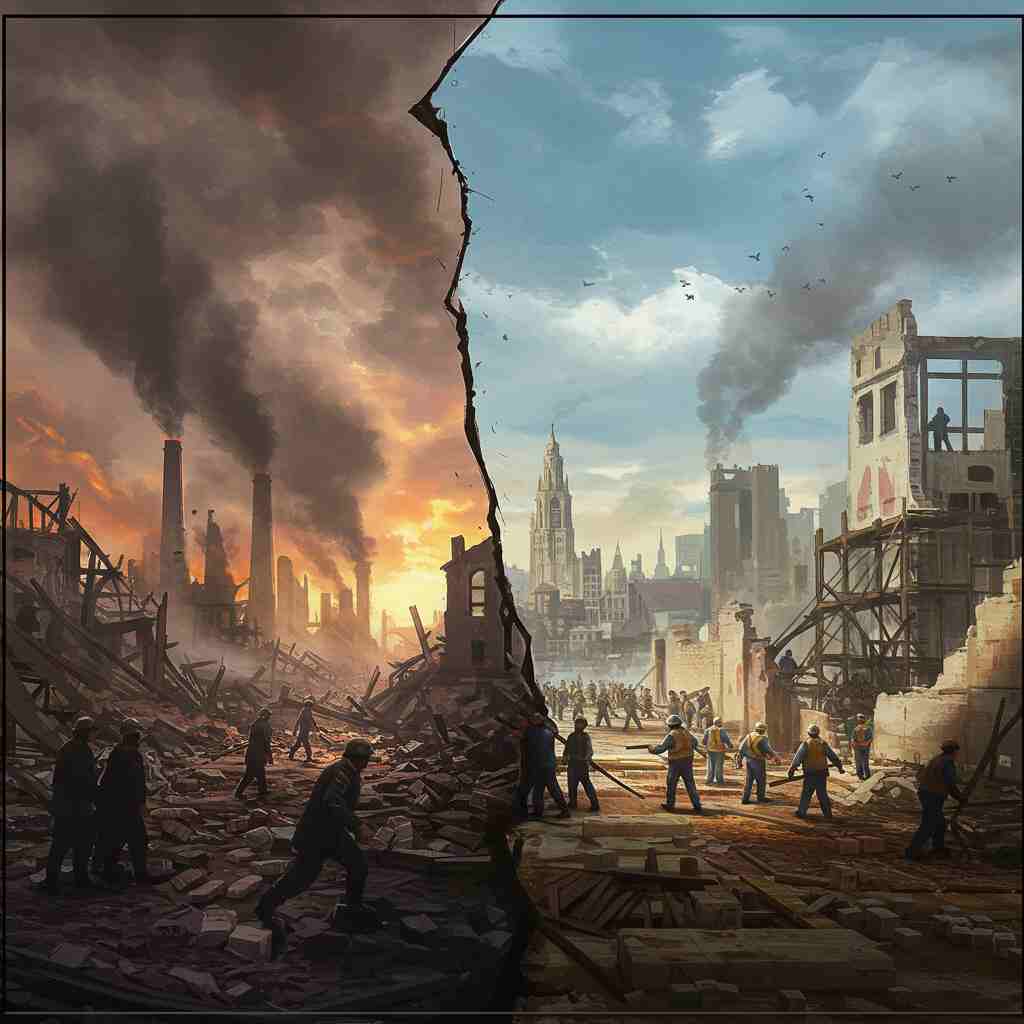

The early 20th century was a time of both unprecedented construction and devastation. The rise of skyscrapers, factories, and urban sprawl coexisted with the ruins left by economic collapse and warfare. Sandburg’s poem captures this duality—the simultaneous breaking and remaking of civilization. The imperative tone ("Smash down the cities," "Build up the cities") suggests an unseen authority dictating these actions, perhaps a metaphor for governments, economic systems, or even fate itself. The soldiers and workers, though ostensibly the agents of change, are rendered passive in their obedience, raising questions about autonomy and coercion in modern society.

Literary Devices and Structure

The poem is divided into two symmetrical stanzas, each mirroring the other in structure but opposing in content. The first stanza commands destruction; the second, reconstruction. This binary structure reinforces the cyclical nature of human endeavor—what is torn down must be rebuilt, only to potentially face destruction again. The repetition of "You are the soldiers and we command you" and "You are workmen and citizens all / We command you" underscores the hierarchical relationship between those who give orders and those who follow them.

Sandburg employs imperative verbs ("Smash," "Knock," "Break," "Build," "Set," "Put") to create a tone of absolute authority. The lack of personal pronouns for the commanders ("we command you") anonymizes power, suggesting that the forces dictating these actions are systemic rather than individual. The imagery is visceral and concrete: "loose piles of stone and lumber and black burnt wood" evokes the aftermath of bombing raids or natural disasters, while "buildings for life and labor" suggests renewal but also hints at the relentless grind of industrial society.

The absence of figurative language—no metaphors, similes, or overt symbolism—lends the poem a stark, almost brutalist quality. Sandburg’s style here is reminiscent of Imagism, a modernist movement that favored precise, unadorned language. Yet, despite its simplicity, the poem carries profound implications about human existence under systems of control.

Themes: Power, Obedience, and the Cycles of History

1. The Illusion of Agency

The most striking theme in "And they Obey" is the tension between action and obedience. The soldiers and workers are addressed directly, yet their roles are purely reactive—they do not question or resist. The phrase "And they Obey" (implied though not explicitly stated in the text) hangs over the poem like a silent verdict. This raises philosophical questions: Do individuals truly have free will within societal structures, or are they merely instruments of larger forces?

The poem echoes Marxist critiques of labor alienation, where workers become cogs in a machine, building and destroying without personal stake. It also recalls Hannah Arendt’s concept of the "banality of evil," where ordinary people carry out orders without moral reflection. Sandburg does not condemn the workers or soldiers but instead highlights their subjugation to an impersonal authority.

2. Destruction and Renewal as Inevitable Cycles

The poem’s two-stanza structure mirrors the myth of eternal recurrence—the idea that history repeats itself in endless loops. This concept appears in Nietzschean philosophy and ancient mythologies (e.g., the Phoenix rising from ashes). Sandburg’s depiction of cities being smashed and rebuilt suggests that human progress is not linear but cyclical, with each era doomed to repeat the follies of the past.

This theme was particularly relevant in the wake of World War I, which was touted as "the war to end all wars," only to be followed by even greater devastation in World War II. Sandburg’s poem subtly critiques the naivete of believing in permanent peace or unbroken progress.

3. The Dehumanization of Labor

The shift from "soldiers" to "workmen and citizens" blurs the line between wartime and peacetime roles. In both cases, individuals are reduced to their function—destroyers or builders—rather than being seen as fully realized human beings. The phrase "You are workmen and citizens all" is particularly telling: even in peacetime, identity is tied to productivity. Sandburg, a champion of the working class, here critiques how labor under capitalism (or any authoritarian system) strips individuals of autonomy.

Comparative Analysis

Sandburg’s poem can be fruitfully compared to other works that explore similar themes:

-

Bertolt Brecht’s "A Worker Reads History" – Both poems interrogate who truly shapes history, suggesting that laborers and soldiers bear the brunt of elite decisions.

-

Wilfred Owen’s "Dulce et Decorum Est" – While Owen focuses on the horrors of war, Sandburg’s poem extends the critique to postwar reconstruction, showing how both phases are dictated from above.

-

T.S. Eliot’s "The Waste Land" – Both depict civilizations in ruin, though Eliot’s tone is more despairing, whereas Sandburg’s retains a grim, pragmatic edge.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Resonance

Despite its brevity, "And they Obey" carries a heavy emotional weight. The absence of personal lamentation makes the poem all the more chilling—it is a clinical observation of how power operates. Readers may feel a sense of futility, recognizing themselves in the obedient masses who follow orders without question. Yet there is also a quiet defiance in Sandburg’s framing: by laying bare this dynamic, he invites us to question it.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with existentialist thought—humans are thrust into systems not of their making, yet they must navigate (or resist) them. It also resonates with absurdism: the endless cycle of building and destruction mirrors Camus’ myth of Sisyphus, condemned to roll a boulder uphill forever.

Conclusion

"And they Obey" is a masterful distillation of Sandburg’s concerns—power, labor, and the repetitive nature of history. Its minimalist style belies its depth, offering a meditation on human obedience and the forces that command it. Written in the shadow of war and industrialization, the poem remains eerily relevant in an age of recurring conflicts and economic precarity. Sandburg does not provide answers but instead holds up a mirror, asking us to see—and perhaps challenge—the systems that demand our obedience.

In its unflinching clarity, the poem achieves what all great poetry should: it disturbs, provokes, and lingers in the mind long after reading.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!