Trafficker

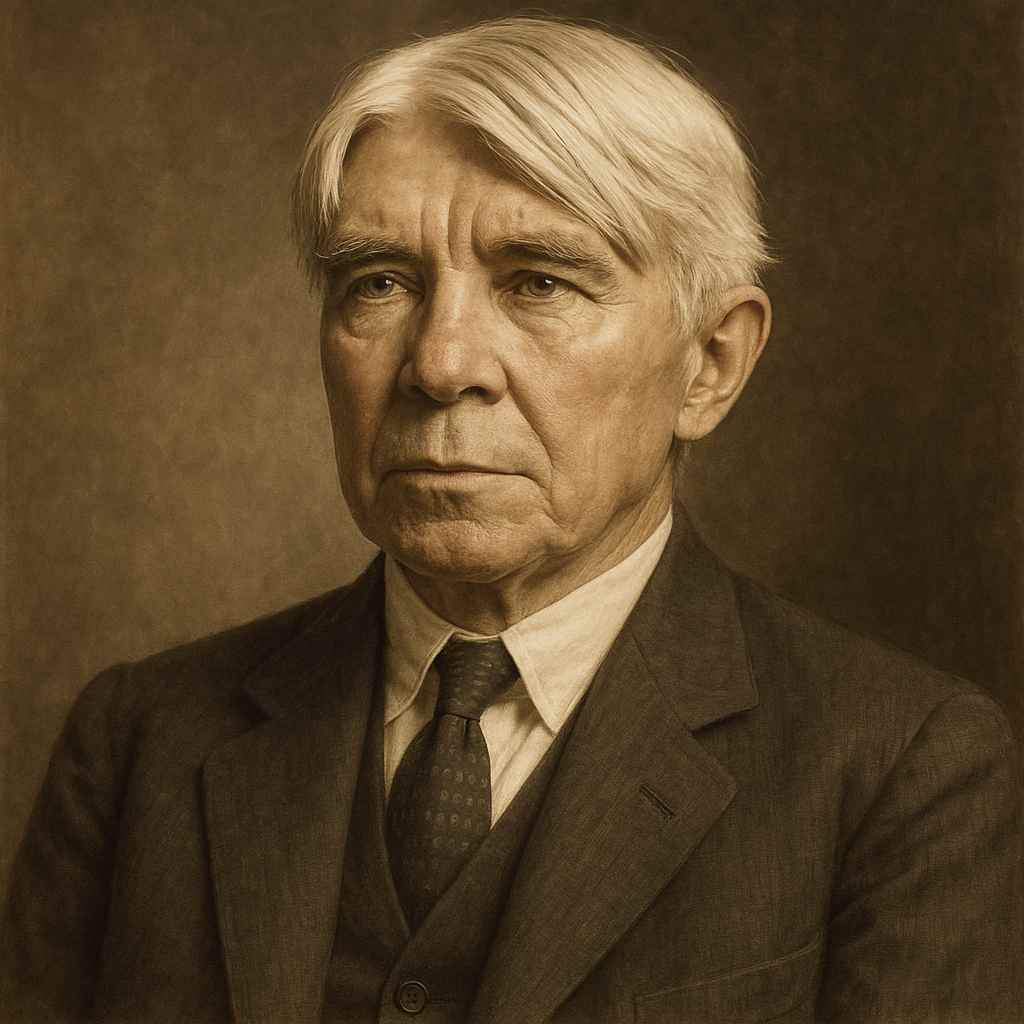

Carl Sandburg

1878 to 1967

Among the shadows where two streets cross,

A woman lurks in the dark and waits

To move on when a policeman heaves in view

Smiling a broken smile from a face

Painted over haggard bones and desperate eyes,

All night she offers passers-by what they will

Of her beauty wasted, body faded, claims gone,

And no takers.

Carl Sandburg's Trafficker

Carl Sandburg’s "Trafficker" is a stark, unflinching portrait of urban decay and human desperation, encapsulating the harsh realities faced by marginalized individuals in early 20th-century America. Through sparse yet evocative imagery, Sandburg constructs a scene of abjection—a woman reduced to a spectral figure in the shadows, her body commodified, her dignity eroded. The poem’s brevity belies its depth, as Sandburg employs a naturalist lens to expose the brutal intersections of poverty, gender, and systemic neglect. This analysis will explore the poem’s historical context, its use of literary devices, its thematic concerns, and its enduring emotional resonance.

Historical and Socioeconomic Context

Sandburg, a poet deeply entrenched in the American modernist movement, was renowned for his depictions of working-class life and urban grit. Writing during the early 1900s—a period marked by industrialization, mass urbanization, and widening economic disparity—Sandburg often turned his gaze toward society’s forgotten figures. "Trafficker" emerges from this milieu, where prostitution was not merely a moral failing but a symptom of broader societal failures: lack of economic opportunity for women, inadequate social welfare, and the criminalization of poverty.

The poem’s setting—"among the shadows where two streets cross"—suggests a liminal space, both geographically and socially. The woman exists on the margins, neither fully visible nor entirely hidden, her presence tolerated only so long as she remains unobtrusive. The looming threat of the policeman underscores the precariousness of her existence; she is not just selling her body but also evading the law, which seeks to erase her from public view rather than address the conditions that force her into such survival tactics.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Sandburg’s language is economical yet devastating in its precision. The woman "lurks in the dark and waits," a phrase that conveys both stealth and exhaustion. The verb "lurks" carries connotations of criminality, reinforcing societal judgment, while "waits" suggests a weariness, an inevitability to her circumstance. She is not an active agent but a figure trapped in a cycle of desperation.

The description of her "broken smile" is particularly haunting. A smile, typically an expression of joy or warmth, is here fractured—perhaps forced, perhaps a remnant of a former self. The face is "painted over haggard bones," an image that evokes both the artifice of makeup and the skeletal reality beneath. This duality speaks to the commodification of her body: she must perform desirability even as her physical and emotional vitality withers.

The phrase "desperate eyes" is a masterstroke of understatement. Rather than elaborate on her suffering, Sandburg lets those two words carry the weight of her interiority. Desperation is not just an emotion here; it is a state of being, one that defines her existence.

The final lines—"All night she offers passers-by what they will / Of her beauty wasted, body faded, claims gone, / And no takers"—are a devastating culmination. The enjambment between "what they will" and "Of her beauty wasted" suggests the transactional nature of her existence, while "claims gone" implies a complete loss of personal agency or societal recognition. The phrase "no takers" is the cruelest blow: even in her abjection, she is denied the minimal economic exchange that might justify her degradation.

Themes: Commodification, Desolation, and Invisibility

At its core, "Trafficker" is a meditation on the commodification of the human body, particularly the female body, within capitalist structures. The woman is reduced to a product, her worth contingent on the fleeting desires of passersby. Yet, in a bitter irony, she is no longer even a viable commodity—her "beauty wasted, body faded" renders her obsolete in an economy that values youth and vitality.

The theme of invisibility is equally potent. The woman exists in the shadows, unseen except as a nuisance or a temptation. The policeman’s presence is a reminder of how society polices poverty rather than alleviating it; the law does not protect her but instead forces her further into the margins.

Sandburg’s portrayal also raises questions about agency. The woman does not speak; she is spoken about, observed, pitied, or condemned. Her silence is emblematic of the broader silencing of impoverished women in public discourse. She is a figure to be moved along, not listened to.

Comparative and Philosophical Readings

Sandburg’s poem invites comparison with other works of urban realism, such as Charles Baudelaire’s "To a Passerby" or T.S. Eliot’s "The Waste Land," both of which depict fleeting, ghostly encounters in the city. However, where Baudelaire’s fleeting beauty evokes romantic melancholy, Sandburg’s woman is stripped of any romanticism—she is pure material suffering.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with Marxist critiques of alienation under capitalism. The woman’s body is not her own; it is a site of labor, exploitation, and eventual discard. Her "claims gone" suggests the erasure of personhood—she is no longer a subject but an object in the machinery of urban survival.

Emotional Impact and Contemporary Relevance

What makes "Trafficker" so enduringly powerful is its refusal to sensationalize or sentimentalize. Sandburg does not ask for the reader’s pity; he simply presents the scene with brutal clarity. The emotional weight comes from the accumulation of small, precise details—the broken smile, the painted face, the desperate eyes.

The poem remains tragically relevant today, as homelessness, sex work, and systemic neglect persist in modern cities. The woman in "Trafficker" could easily be a figure in a 21st-century urban landscape, still waiting, still unseen.

Conclusion

Carl Sandburg’s "Trafficker" is a masterclass in economical yet profound poetry, using stark imagery to expose the dehumanizing effects of poverty and commodification. It is a poem that does not flinch, that refuses to offer easy answers or false comforts. Instead, it forces the reader to confront an uncomfortable truth: that society’s most vulnerable are often rendered invisible until they are no longer useful, and even then, their suffering is met with indifference. In its brevity, "Trafficker" achieves what the best poetry does—it compels us to see, to feel, and, perhaps, to act.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!