Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

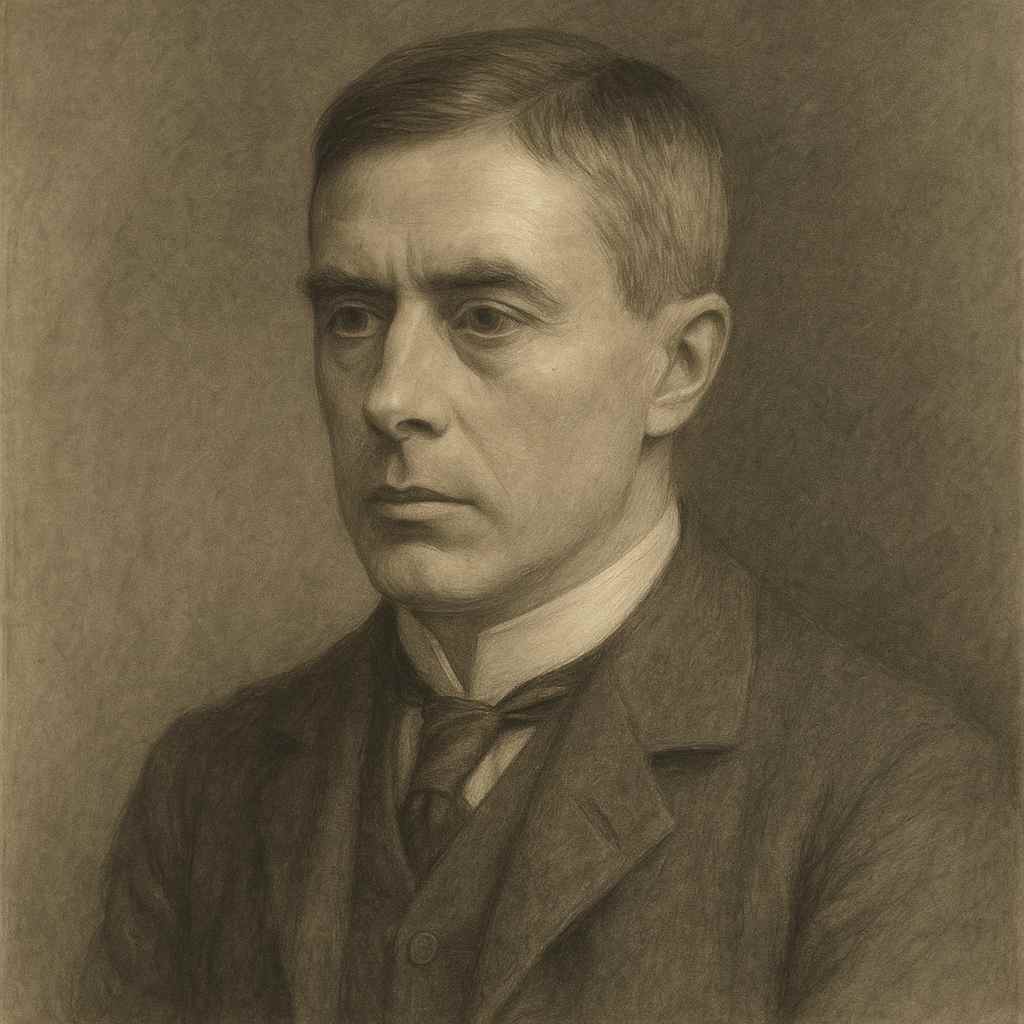

A.E.Housman

1859 to 1936

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

A.E.Housman's Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

A.E. Housman's "Loveliest of trees, the cherry now" is a poignant meditation on the transience of life and the beauty of nature, encapsulated in the image of a blooming cherry tree. The poem, part of Housman's collection "A Shropshire Lad," employs a deceptively simple structure to convey profound themes of mortality, time, and the human relationship with the natural world.

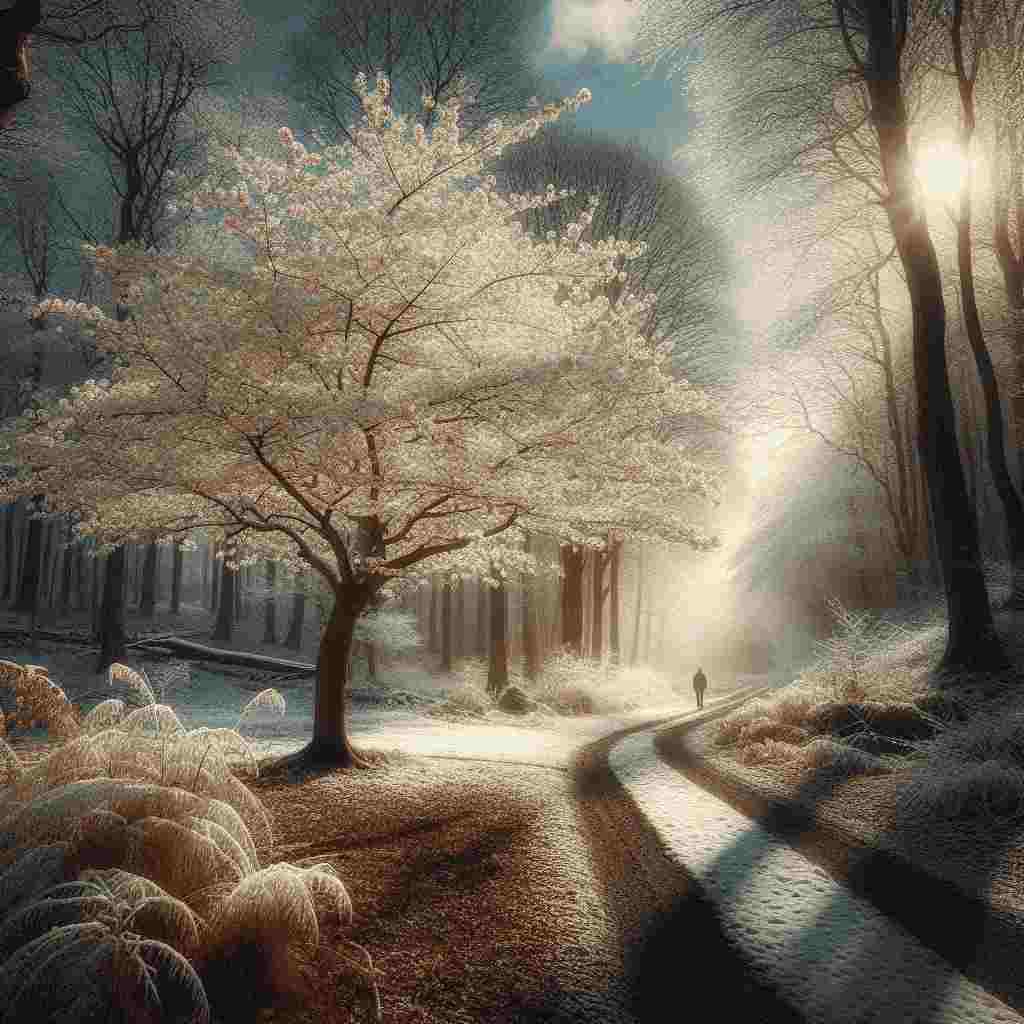

The poem opens with a vivid description of the cherry tree in full bloom, its white blossoms likened to snow. This imagery immediately establishes a sense of natural beauty and purity, with the tree "wearing white for Eastertide." The reference to Easter is significant, as it connotes themes of rebirth and renewal, juxtaposed against the underlying awareness of life's brevity that emerges in the subsequent stanzas.

Housman's use of the traditional ballad meter, with its alternating lines of iambic tetrameter and trimeter, lends the poem a song-like quality that belies its weighty subject matter. This musical quality is further enhanced by the AABB rhyme scheme, which creates a sense of harmony and continuity throughout the piece. The simplicity of the language and structure contrasts with the complexity of the emotions and ideas being explored, a hallmark of Housman's style.

In the second stanza, the speaker introduces a personal element, contemplating his own mortality within the context of the biblical lifespan of "threescore years and ten." The realization that twenty years have already passed leads to a simple yet poignant calculation: only fifty springs remain. This stark acknowledgment of life's finitude creates a sense of urgency and melancholy that permeates the remainder of the poem.

The final stanza resolves this tension between the beauty of nature and the brevity of human life. Rather than succumbing to despair, the speaker determines to make the most of his remaining time by immersing himself in the natural world. The decision to go "about the woodlands" to see the cherry "hung with snow" represents a conscious choice to appreciate beauty while it lasts, both in nature and in life.

Housman's use of imagery is particularly effective in this poem. The cherry tree serves as a multifaceted symbol, representing both the cyclical nature of life and its ephemeral quality. The white blossoms evoke purity and beauty, but their short-lived nature also underscores the transience of all things. The comparison of the blossoms to snow in the final line creates a circular structure, linking back to the opening imagery and suggesting the continuity of natural cycles beyond individual human lifespans.

The poem's exploration of time is nuanced and complex. While acknowledging the limited nature of human existence, it also celebrates the recurring beauty of each spring. This tension between linear human time and cyclical natural time creates a bittersweet tone that is characteristic of much of Housman's work.

Moreover, the poem can be read as a carpe diem exhortation, encouraging readers to seize the day and appreciate the beauty around them while they can. However, unlike many poems in this tradition, Housman's work is tinged with a melancholy acceptance of mortality rather than a hedonistic embrace of pleasure.

In conclusion, "Loveliest of trees, the cherry now" exemplifies Housman's ability to distill complex philosophical and emotional concepts into accessible, lyrical verse. Through its elegant structure, evocative imagery, and thoughtful exploration of time and mortality, the poem offers a meditation on the human condition that remains relevant and moving. It encourages readers to contemplate their own relationship with nature and time, ultimately advocating for a life lived in appreciation of beauty, however fleeting it may be.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!