A Little Called Pauline

Gertrude Stein

1874 to 1946

A little called anything shows shudders.

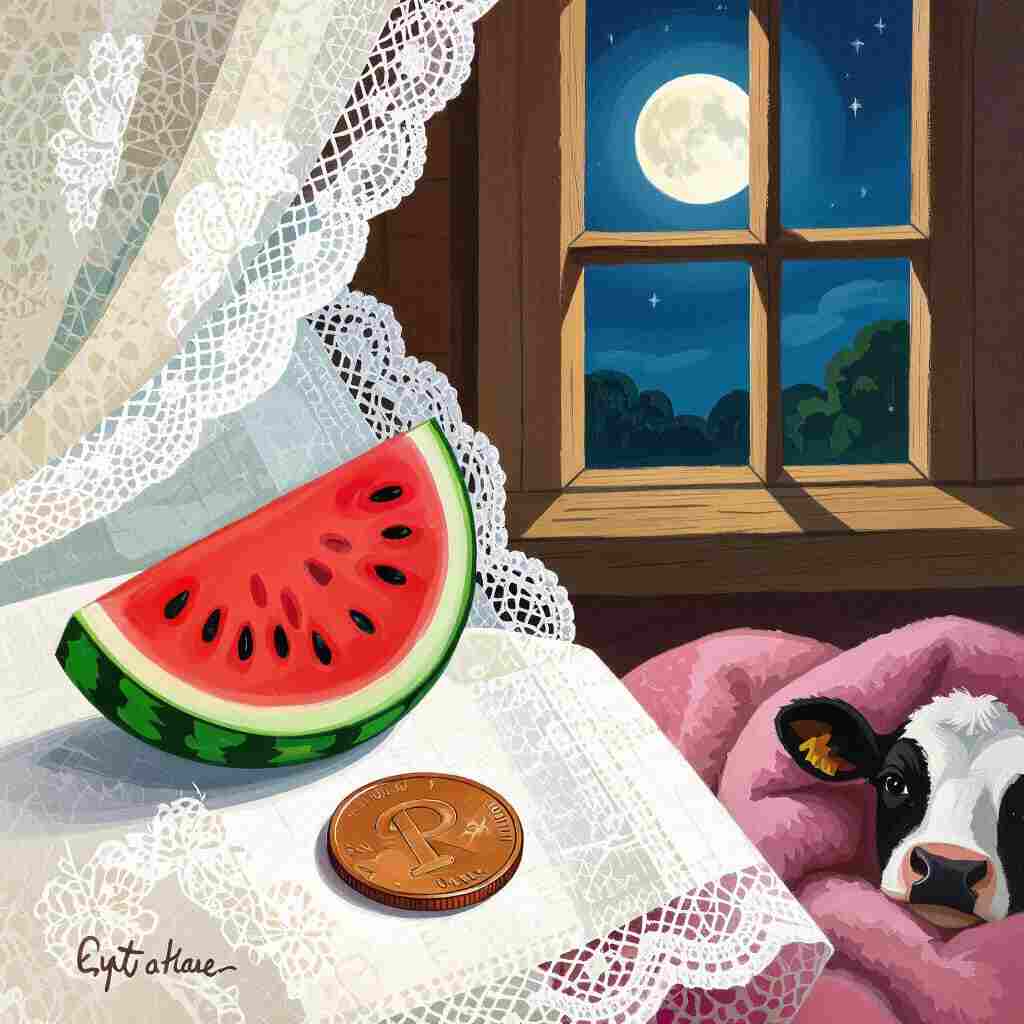

Come and say what prints all day. A whole few watermelon. There is no pope.

No cut in pennies and little dressing and choose wide soles and little spats really little spices.

A little lace makes boils. This is not true.

Gracious of gracious and a stamp a blue green white bow a blue green lean, lean on the top.

If it is absurd then it is leadish and nearly set in where there is a tight head.

A peaceful life to arise her, noon and moon and moon. A letter a cold sleeve a blanket a shaving house and nearly the best and regular window.

Nearer in fairy sea, nearer and farther, show white has lime in sight, show a stitch of ten. Count, count more so that thicker and thicker is leaning.

I hope she has her cow. Bidding a wedding, widening received treading, little leading mention nothing.

Cough out cough out in the leather and really feather it is not for.

Please could, please could, jam it not plus more sit in when.

Gertrude Stein's A Little Called Pauline

Gertrude Stein’s "A Little Called Pauline" is a striking example of modernist experimentation, a poem that defies conventional interpretation while inviting readers into a labyrinth of linguistic play, cultural subversion, and emotional ambiguity. Written during a period of radical artistic upheaval, the poem reflects Stein’s broader literary project—one that dismantles syntactic norms, challenges semantic expectations, and reconfigures language as a medium of sensory and cognitive experience rather than straightforward communication.

To engage meaningfully with this work, one must consider its historical and cultural milieu, its deployment of avant-garde literary techniques, its thematic preoccupations, and the visceral, often disorienting emotional response it elicits. While the poem resists definitive explication, its very resistance opens up a space for rich analysis, positioning it as a vital artifact of early 20th-century modernism.

Historical and Cultural Context: Stein and the Avant-Garde

Gertrude Stein was a central figure in the modernist movement, both as a writer and as a patron of the arts. Residing in Paris during the early 1900s, she cultivated relationships with groundbreaking artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Juan Gris, while her literary salons became incubators for experimental thought. Her writing, much like Cubist painting, sought to fragment and reassemble reality, rejecting linear narrative in favor of simultaneity, repetition, and abstraction.

"A Little Called Pauline" exemplifies Stein’s commitment to linguistic innovation, a hallmark of her broader oeuvre, including works like Tender Buttons (1914) and The Making of Americans (1925). The poem’s publication coincided with a period of intense artistic ferment—a time when writers like James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot were similarly deconstructing traditional forms. However, Stein’s approach was distinct in its relentless focus on the materiality of language itself.

The title character, "Pauline," remains enigmatic, but the name’s recurrence in Stein’s work suggests a semi-autobiographical or symbolic presence. Some critics speculate that Pauline may represent an alter ego or a composite of women in Stein’s life, including her partner, Alice B. Toklas. The poem’s resistance to clear referentiality aligns with Stein’s belief that language should evoke rather than describe, a principle she termed "continuous present."

Literary Devices: Dislocation and Repetition

Stein’s poem thrives on dislocation—grammatical, semantic, and rhythmic. The opening line, "A little called anything shows shudders," immediately destabilizes meaning. The phrase "a little called anything" suggests a provisional naming, an arbitrary designation that nevertheless provokes a physical reaction ("shudders"). This tension between linguistic arbitrariness and bodily response recurs throughout the poem, reinforcing Stein’s interest in how words generate sensation rather than fixed ideas.

Repetition functions as both a structural and thematic device. Phrases such as "little leading mention nothing" and "nearer and farther" create a hypnotic cadence, while their slight variations resist resolution. This technique mirrors the Cubist method of presenting multiple perspectives simultaneously, refusing to settle on a single, stable image.

Juxtaposition is another critical strategy. The line "A whole few watermelon. There is no pope." places the mundane alongside the sacrilegious, undermining hierarchical distinctions between the trivial and the profound. Stein’s abrupt shifts—from domestic details ("little spices," "a blanket") to surreal declarations ("If it is absurd then it is leadish")—disrupt conventional logic, forcing the reader to engage with language on a purely associative level.

Themes: Language, Identity, and the Everyday

At its core, "A Little Called Pauline" interrogates the instability of language and identity. The poem’s title implies that naming is arbitrary ("a little called anything"), and the text itself refuses to cohere into a definitive portrait of Pauline. Instead, identity is presented as a series of fleeting impressions—some domestic ("little dressing," "a shaving house"), some abstract ("Gracious of gracious and a stamp a blue green white bow").

The domestic sphere emerges as a site of both comfort and strangeness. References to household objects ("a cold sleeve," "regular window") are interspersed with incongruous imagery ("nearly the best and regular window"), suggesting that even the familiar is rendered unfamiliar through linguistic play. This aligns with Stein’s broader fascination with the defamiliarization of everyday experience, a concept later theorized by Russian Formalists like Viktor Shklovsky.

Absurdity and humor also permeate the poem. The line "A little lace makes boils. This is not true." undercuts its own assertion, enacting a kind of self-aware mockery of declarative statements. Stein’s wit here is reminiscent of Dadaist anti-art gestures, which sought to expose the arbitrary nature of cultural norms.

Emotional Impact: Disorientation and Intimacy

The emotional resonance of "A Little Called Pauline" lies in its paradoxical combination of detachment and intimacy. The poem’s fragmented syntax creates a sense of distance, yet its rhythmic repetitions and sudden flashes of clarity ("I hope she has her cow.") evoke an almost childlike sincerity. This duality reflects Stein’s ability to balance intellectual rigor with emotional vulnerability.

The closing lines—"Please could, please could, jam it not plus more sit in when."—oscillate between pleading and nonsense, leaving the reader in a state of unresolved tension. There is no catharsis, only the lingering sensation of language as a living, unstable entity.

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

Stein’s work invites comparison with other modernist writers. Like James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, her poetry revels in linguistic multiplicity, though her approach is more minimalist and incantatory. Similarly, her focus on the materiality of language aligns with later Language poets, such as Lyn Hejinian, who viewed words as objects in themselves rather than mere signifiers.

Philosophically, Stein’s work resonates with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s investigations into language games and the limits of meaning. Both thinkers challenge the assumption that language transparently reflects reality, instead highlighting its constructed, rule-bound nature.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Stein’s Experimentation

"A Little Called Pauline" is not a poem that yields easy interpretations, nor was it meant to. Its brilliance lies in its refusal to conform, its insistence on linguistic freedom, and its ability to evoke emotion through dislocation. By destabilizing grammar and meaning, Stein invites readers to experience language anew—to feel its textures, rhythms, and contradictions rather than simply decode it.

In this sense, the poem is not just a product of its historical moment but a living challenge to conventional reading practices. It demands active engagement, rewarding those willing to surrender to its musicality and mystery. For contemporary readers, Stein’s work remains a vital reminder of poetry’s capacity to disrupt, delight, and defy.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!