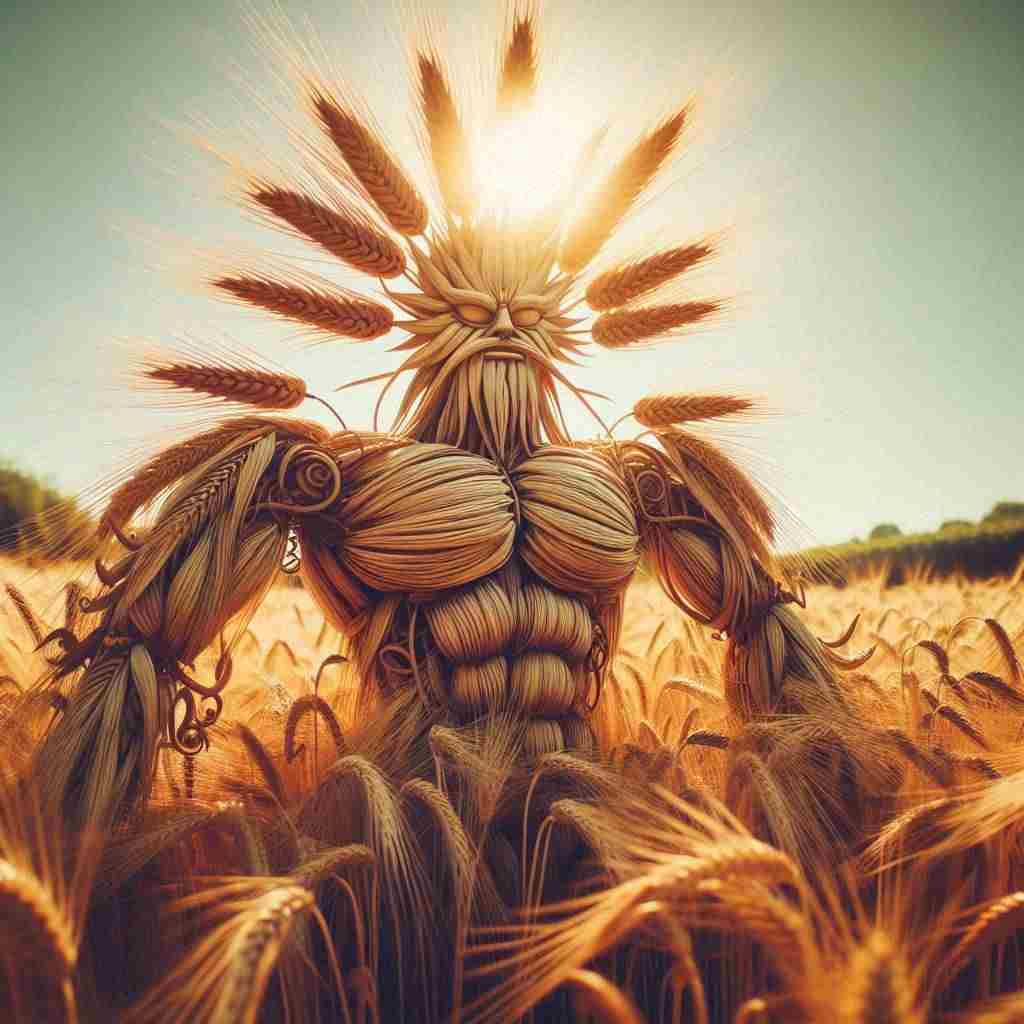

John Barleycorn

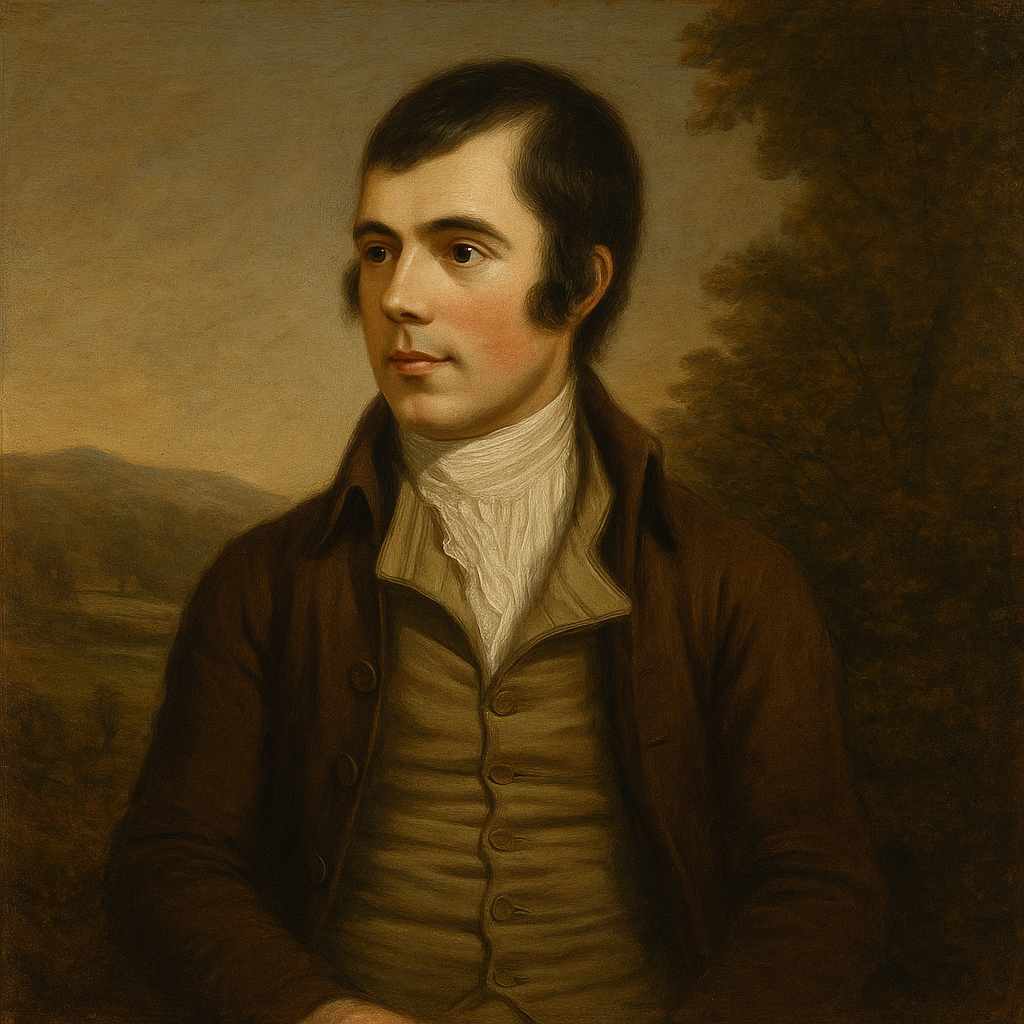

Robert Burns

1759 to 1796

There was three kings into the east,

Three kings both great and high,

And they hae sworn a solemn oath

John Barleycorn should die.

They took a plough and plough'd him down,

Put clods upon his head,

And they hae sworn a solemn oath

John Barleycorn was dead.

But the cheerful Spring came kindly on,

And show'rs began to fall;

John Barleycorn got up again,

And sore surpris'd them all.

The sultry suns of Summer came,

And he grew thick and strong;

His head weel arm'd wi' pointed spears,

That no one should him wrong.

The sober Autumn enter'd mild,

When he grew wan and pale;

His bending joints and drooping head

Show'd he began to fail.

His colour sicken'd more and more,

He faded into age;

And then his enemies began

To show their deadly rage.

They've taen a weapon, long and sharp,

And cut him by the knee;

Then tied him fast upon a cart,

Like a rogue for forgerie.

They laid him down upon his back,

And cudgell'd him full sore;

They hung him up before the storm,

And turned him o'er and o'er.

They filled up a darksome pit

With water to the brim;

They heaved in John Barleycorn,

There let him sink or swim.

They laid him out upon the floor,

To work him farther woe;

And still, as signs of life appear'd,

They toss'd him to and fro.

They wasted, o'er a scorching flame,

The marrow of his bones;

But a miller us'd him worst of all,

For he crush'd him between two stones.

And they hae taen his very heart's blood,

And drank it round and round;

And still the more and more they drank,

Their joy did more abound.

John Barleycorn was a hero bold,

Of noble enterprise;

For if you do but taste his blood,

'Twill make your courage rise

'Twill make a man forget his woe;

'Twill heighten all his joy;

'Twill make the widow's heart to sing,

Tho' the tear were in her eye.

Then let us toast John Barleycorn,

Each man a glass in hand;

And may his great posterity

Ne'er fail in old Scotland!

Robert Burns's John Barleycorn

Introduction

Robert Burns' "John Barleycorn" stands as a testament to the enduring power of folklore and allegory in poetry. This 18th-century Scottish ballad, with its roots deeply embedded in the agricultural traditions of Britain, weaves a tale that is simultaneously simple and profoundly complex. At its surface, the poem narrates the life cycle of barley, from sowing to harvest and eventual transformation into alcohol. However, beneath this agricultural narrative lies a rich tapestry of symbolism, exploring themes of death, rebirth, sacrifice, and the human relationship with nature and spirituous liquors.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate "John Barleycorn," one must first understand its place within the broader context of British folk traditions. The personification of grain as a human figure dates back to ancient agrarian societies, where the cycle of planting, growth, and harvest was often imbued with religious and mythological significance. Burns, writing in the late 18th century, taps into this deep well of cultural memory, reviving and reimagining an old folk song for a new audience.

The poem's structure, with its ballad meter and use of repetition, echoes the oral traditions from which it emerged. Burns' genius lies in his ability to elevate this folk material, infusing it with literary craft while maintaining its rustic charm. The result is a work that resonates on multiple levels, speaking to both the common laborer and the educated elite of Burns' time.

Narrative Structure and Symbolism

"John Barleycorn" unfolds as a narrative allegory, chronicling the "life" of its titular character from his metaphorical birth to death and resurrection. The poem begins with a conspiracy among three kings, setting a tone of high drama that contrasts with the agricultural subject matter. This opening immediately elevates John Barleycorn to the status of a tragic hero, foreshadowing the trials he will endure.

The subsequent stanzas follow the agricultural calendar, each season bringing new challenges and transformations for John Barleycorn. Spring sees his resurrection, summer his maturation, autumn his decline, and winter his brutal "death" at the hands of his enemies. This cyclical structure mirrors not only the agricultural year but also mythological narratives of dying and rising gods, lending the poem a universal, almost archetypal quality.

Burns' use of violent imagery throughout the poem is particularly striking. John Barleycorn is not simply harvested; he is "cut... by the knee," "cudgell'd... full sore," and has "the marrow of his bones" wasted "o'er a scorching flame." This graphic depiction of the harvest and brewing process serves multiple purposes. It heightens the poem's dramatic tension, anthropomorphizes the barley to elicit sympathy from the reader, and subtly comments on the brutality inherent in agricultural labor.

Themes of Transformation and Resilience

Central to "John Barleycorn" is the theme of transformation. The barley undergoes numerous changes throughout the poem, from seed to sprout, from plant to beverage. This metamorphosis can be read as a metaphor for human resilience in the face of adversity. Despite the violent attempts to destroy him, John Barleycorn ultimately triumphs, transformed into a source of joy and comfort for those who "taste his blood."

This transformation carries religious overtones, particularly in the imagery of John Barleycorn's blood being drunk "round and round." The parallel to the Christian Eucharist is unmistakable, elevating the act of drinking to a quasi-religious experience. Burns thus blurs the line between the sacred and the profane, suggesting that spiritual transcendence can be found in the mundane act of sharing a drink.

Social Commentary and Ambivalence

While "John Barleycorn" can be read as a celebration of alcohol's ability to uplift the human spirit, it also contains a subtle critique of its effects on society. The poem acknowledges alcohol's power to "make a man forget his woe" and "heighten all his joy," but it does so with a hint of irony. The image of the singing widow "Tho' the tear were in her eye" is particularly poignant, suggesting that alcohol's comfort may be illusory or short-lived.

Burns' ambivalence towards his subject is further reflected in the poem's structure. While the majority of the poem details John Barleycorn's suffering, the final stanzas pivot to a celebratory tone, calling for a toast to "his great posterity." This sudden shift creates a sense of unease, forcing the reader to reconcile the violence of John Barleycorn's "death" with the joy his transformation brings.

Language and Poetic Technique

Burns' mastery of language is evident throughout "John Barleycorn." His use of Scots dialect words and phrases ("hae," "weel," "taen") grounds the poem in its cultural context while adding to its musical quality. The ballad stanza form, with its alternating tetrameter and trimeter lines, creates a rhythmic structure that mimics the cyclical nature of the agricultural process it describes.

Particularly noteworthy is Burns' use of personification. John Barleycorn is not merely described in human terms; he is imbued with human qualities and emotions. He is "sore surpris'd" by his resurrection, grows "thick and strong" in summer, and shows signs of "bending joints and drooping head" as he ages. This anthropomorphism creates a powerful emotional connection between the reader and the ostensibly inanimate barley, heightening the impact of the poem's allegorical message.

Conclusion

"John Barleycorn" stands as a masterpiece of allegorical poetry, seamlessly blending folk tradition with literary craftsmanship. Through its vivid personification of barley and its journey from seed to spirit, Burns explores profound themes of life, death, transformation, and the human condition. The poem's enduring appeal lies in its ability to operate on multiple levels simultaneously: as a simple folk ballad, as a complex allegory, and as a nuanced commentary on the role of alcohol in society.

Moreover, "John Barleycorn" exemplifies Burns' talent for elevating the mundane to the mythic. By imbuing the agricultural process with drama and significance, he celebrates the often-overlooked labor that sustains human civilization. In doing so, he creates a work that is at once deeply rooted in its Scottish context and universally resonant.

As we raise our glasses to John Barleycorn, we are not merely toasting a personified grain or the pleasures of alcohol. We are acknowledging the cycles of nature, the resilience of the human spirit, and the transformative power of art to find profound meaning in the simplest of subjects. It is this multifaceted nature that ensures "John Barleycorn" will continue to captivate readers and scholars for generations to come, inviting new interpretations and appreciations with each reading.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!