Keeping a Heart

Arthur O'Shaughnessy

1844 to 1881

If one should give me a heart to keep,

With love for the golden key,

The giver might live at ease or sleep;

It should ne’er know pain, be weary, or weep,

The heart watched over by me.

I would keep that heart as a temple fair,

No heathen should look therein;

Its chaste marmoreal beauty rare

I only should know, and to enter there

I must hold myself from sin.

I would keep that heart as a casket hid

Where precious jewels are ranged,

A memory each; as you raise the lid,

You think you love again as you did

Of old, and nothing seems changed.

How I should tremble day after day,

As I touched with the golden key,

Lest aught in the heart were changed, or say

That another had stolen one thought away

And it did not open to me.

But ah, I should know that heart so well,

As a heart so loving and true,

As a heart that I held with a golden spell,

That so long as I changed not I could foretell

That heart would be changeless too.

I would keep that heart as the thought of heaven,

To dwell in a life apart,

My good should be done, my gift be given,

In hope of the recompense there; yea, even

My life should be led in that heart.

And so on the eve of some blissful day,

From within we should close the door

On glimmering splendours of love, and stay

In that heart shut up from the world away,

Never to open it more.

Arthur O'Shaughnessy's Keeping a Heart

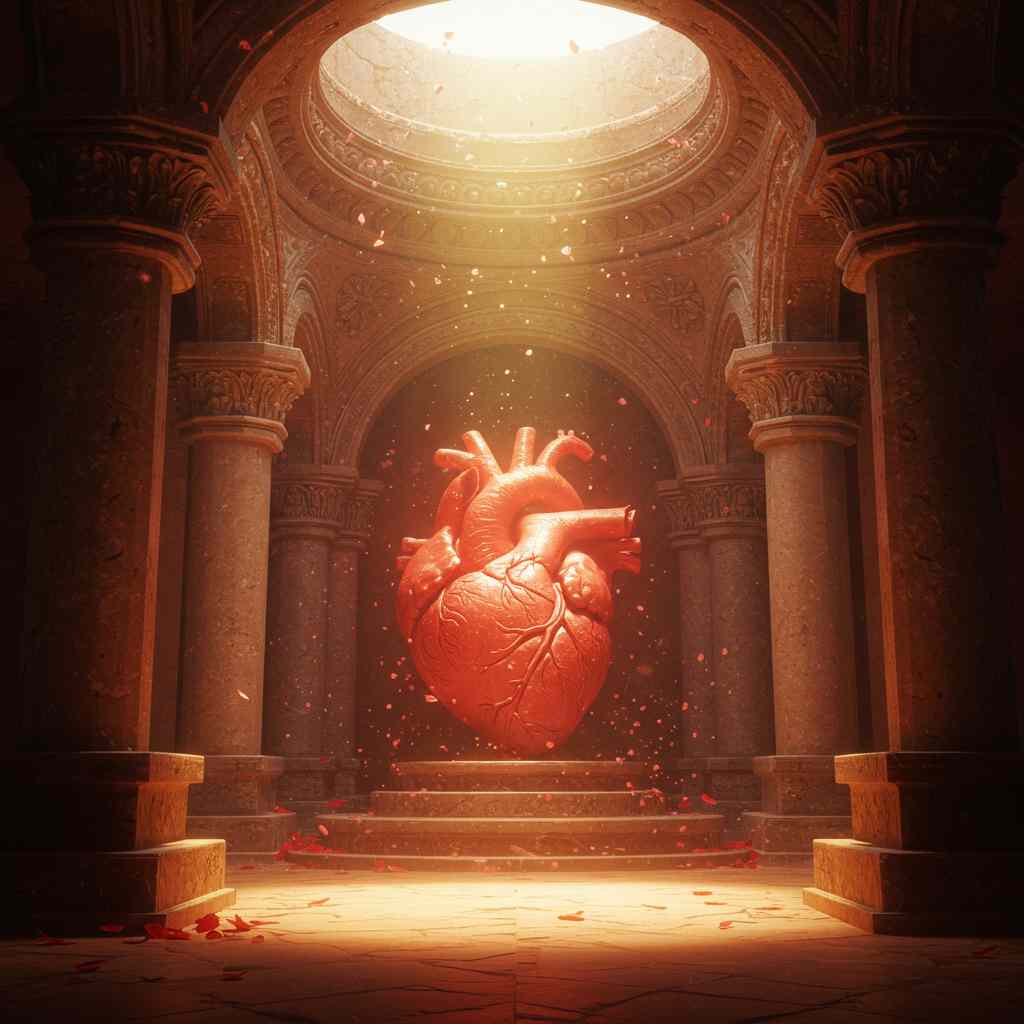

Arthur O'Shaughnessy’s "Keeping a Heart" is a lyrical meditation on love, devotion, and the sacred responsibility of safeguarding another’s emotional core. Written in the Victorian era—a period marked by both romantic idealism and profound anxieties about moral purity—the poem explores the tension between idealization and fear, between the desire to preserve love in its most pristine form and the terror of its potential corruption. Through rich symbolism, religious imagery, and a tone that oscillates between reverence and apprehension, O'Shaughnessy crafts a work that is as much about the fragility of human connection as it is about its transcendent possibilities.

The Sacred and the Secret: The Heart as Temple and Casket

The poem’s central conceit is the heart as an object to be guarded, a treasure entrusted to the speaker. The opening stanza establishes this premise with an almost contractual solemnity:

"If one should give me a heart to keep,

With love for the golden key,"

The "golden key" suggests both privilege and responsibility, evoking the biblical imagery of the keys to the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:19), where guardianship is both an honor and a sacred duty. The heart is not merely an organ but a sanctified space, a "temple fair" that must remain inviolate. The speaker’s vow that the heart "should ne’er know pain, be weary, or weep" underscores a protective impulse, yet it also hints at an impossible ideal—a love untouched by suffering, a heart preserved in perpetual innocence.

This religious framing continues as the speaker describes the heart’s "chaste marmoreal beauty rare," likening it to marble—cold, pure, and unchanging. The insistence that "no heathen should look therein" introduces an element of exclusivity, even possessiveness. The heart is not merely protected; it is sequestered, accessible only to the morally worthy. The speaker’s admission that they "must hold [themself] from sin" to enter this sacred space suggests that love is conditional upon moral purity, a reflection of Victorian anxieties about virtue and temptation.

Yet the poem does not merely frame the heart as a temple; it also imagines it as a "casket hid," a repository of memories. This duality—the heart as both shrine and reliquary—captures the tension between love as a living force and love as a preserved artifact. The image of opening the casket and finding "precious jewels," each a memory that revives past affections, suggests nostalgia’s power to suspend time:

"You think you love again as you did

Of old, and nothing seems changed."

Here, O'Shaughnessy touches on a universal human longing: the desire to return to a moment before loss, before disillusionment. Yet the very need to preserve these memories in a "casket" implies their fragility, their susceptibility to decay or theft.

Fear and Fidelity: The Anxiety of Love’s Mutability

The poem’s middle stanzas introduce a note of dread beneath its devotional surface. The speaker trembles at the thought that the heart might change or that "another had stolen one thought away." This fear is not irrational; it is the inevitable shadow of deep attachment. To love is to risk betrayal, to know that even the most fervent vows cannot guarantee constancy.

Yet the speaker clings to an almost magical belief in reciprocity:

"That so long as I changed not I could foretell

That heart would be changeless too."

This line reveals the poem’s psychological core—the hope that love can be rendered immutable through sheer will, that fidelity in one soul can bind another. It is a beautiful but precarious fantasy, one that ignores love’s inherent unpredictability. The speaker’s faith in the "golden spell" suggests an incantatory power in devotion, as though love itself were a kind of alchemy capable of defying time.

The Heart as Heaven: Love and Spiritual Transcendence

In the final stanzas, the poem ascends into metaphysical reverie. The heart becomes "the thought of heaven," a private paradise where the speaker’s "good should be done, [their] gift be given." This spiritualization of love reflects the Victorian tendency to conflate romantic and religious ecstasy—a tradition seen in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites and poets like Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The closing lines envision a retreat from the world into an eternal, enclosed intimacy:

"And so on the eve of some blissful day,

From within we should close the door

On glimmering splendours of love, and stay

In that heart shut up from the world away,

Never to open it more."

This image is at once transcendent and claustrophobic. The lovers withdraw into a sanctum, shutting out even the "glimmering splendours" of love’s external manifestations. The finality of "Never to open it more" suggests both fulfillment and annihilation—a love so complete that it requires no further engagement with the world. One might read this as a romantic ideal, but also as a kind of death, a sealing away from life’s messiness.

Historical and Biographical Context

Arthur O'Shaughnessy (1844–1881) was a poet and herpetologist associated with the aesthetic movement, which prized beauty and sensory experience over moral or narrative didacticism. His most famous work, "Ode" ("We are the music-makers"), celebrates art’s transformative power, and a similar idealism pervades "Keeping a Heart." Yet where "Ode" is exuberant, "Keeping a Heart" is introspective, even anxious.

The Victorian era’s preoccupation with purity and decay resonates throughout the poem. The heart as a sealed space reflects the period’s gendered ideals of womanhood—the "angel in the house" whose virtue must be protected from corruption. Yet the speaker’s own vulnerability ("How I should tremble day after day") complicates this dynamic, revealing that the guardian, too, is fragile.

Conclusion: The Paradox of Preservation

"Keeping a Heart" is a poem of exquisite contradictions. It yearns for a love that is both eternal and unchanging, yet it trembles at the impossibility of such a wish. It elevates the heart to the status of a sacred relic, yet in doing so, risks rendering it lifeless—a thing to be admired rather than lived.

O'Shaughnessy’s genius lies in his ability to capture the dual nature of devotion: its power to exalt and its capacity to imprison. The poem speaks to anyone who has ever loved fiercely enough to fear loss, who has sought to preserve a perfect moment even as time marches on. In the end, "Keeping a Heart" is not just about love’s preservation but about its peril—the recognition that to hold something too tightly is, perhaps, to lose it all the same.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!