The Friend

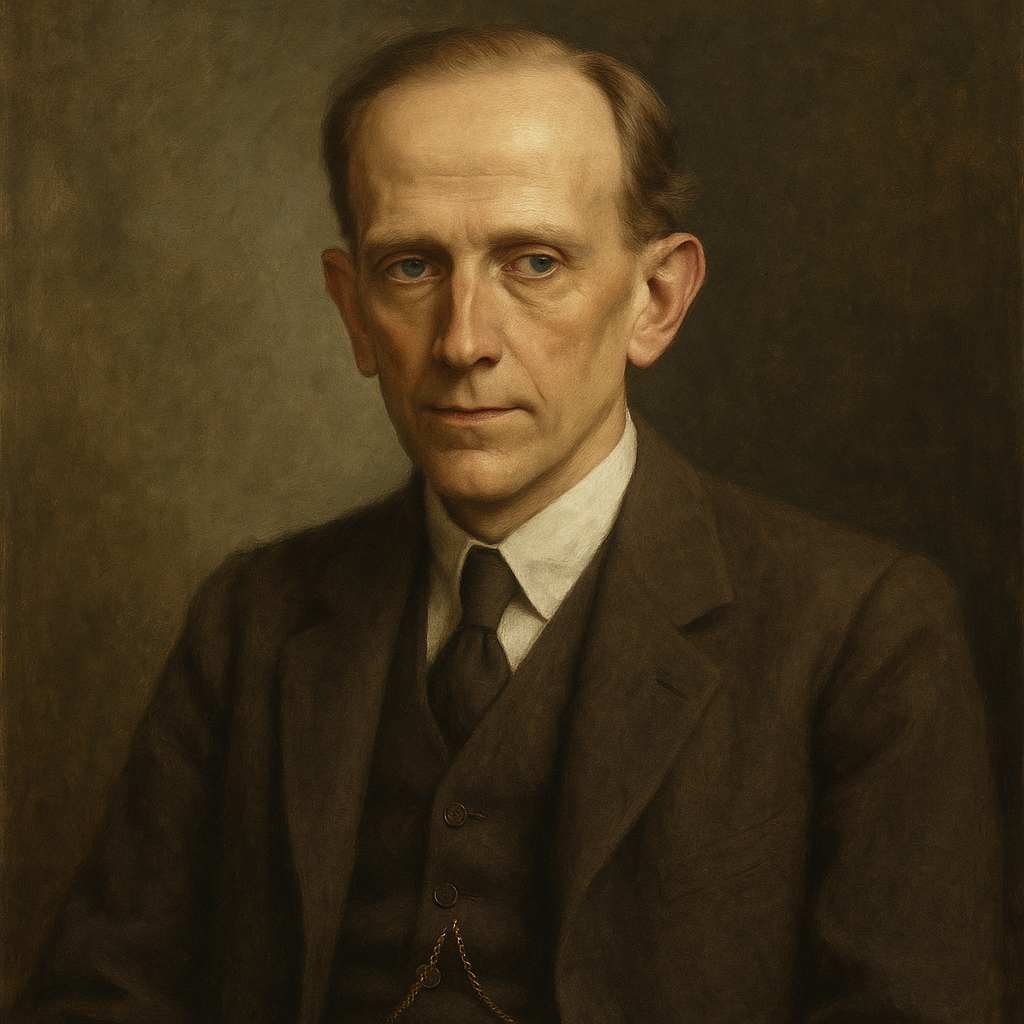

A. A. Milne

1882 to 1956

There are lots and lots of people who are always asking things,

Like Dates and Pounds-and-ounces and the names of funny Kings,

And the answer's either Sixpence or A Hundred Inches Long,

And I know they'll think me silly if I get the answer wrong.

So Pooh and I go whispering, and Pooh looks very bright,

And says, "Well, I say sixpence, but I don't suppose I'm right,"

And then it doesn't matter what the answer ought to be,

'Cos if he's right, I'm Right, and if he's wrong, it isn't Me.

A. A. Milne's The Friend

A. A. Milne’s The Friend is a deceptively simple poem that captures the innocence of childhood companionship while subtly exploring deeper themes of loyalty, self-doubt, and the comfort found in shared uncertainty. Written in Milne’s signature whimsical style, the poem reflects his profound understanding of a child’s psyche, a hallmark of his Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Though brief, the poem resonates emotionally, offering a meditation on friendship as a sanctuary from judgment and failure. This essay will examine The Friend through its historical and cultural context, literary devices, thematic concerns, and emotional impact, while also considering Milne’s biographical influences and philosophical undercurrents.

Historical and Cultural Context

Milne wrote The Friend during the interwar period (the 1920s-1930s), a time when British literature often oscillated between nostalgia for pre-war innocence and the looming anxieties of modernity. Milne’s work, particularly his children’s poetry and the Winnie-the-Pooh series, provided an escape into a world of simplicity and warmth. The poem reflects a post-Victorian shift in attitudes toward childhood—no longer seen merely as a phase of discipline and moral instruction but as a time of imaginative freedom and emotional authenticity.

The reference to "Dates and Pounds-and-ounces and the names of funny Kings" situates the poem within an educational framework familiar to early 20th-century British children, where rote memorization was central to schooling. The child speaker’s anxiety about giving wrong answers mirrors societal pressures to conform to rigid standards of correctness. Yet, the presence of Pooh—a figure of unconditional acceptance—subverts these pressures, suggesting that emotional security outweighs factual precision.

Literary Devices and Structure

Though the poem’s rhyme scheme is not the focus here, its rhythmic cadence and conversational tone are essential to its effect. Milne employs enjambment ("There are lots and lots of people who are always asking things") to mimic the natural flow of a child’s speech, reinforcing authenticity. The repetition of "right" and "wrong" underscores the speaker’s preoccupation with correctness, while the personification of Pooh ("Pooh looks very bright") elevates the stuffed bear to the status of a sentient confidant.

The poem’s dramatic irony lies in the adult reader’s awareness that Pooh is merely a toy, while the child invests him with wisdom. This irony deepens the emotional resonance, as the reader recognizes the child’s need for reassurance. The dialogue between the speaker and Pooh ("Well, I say sixpence, but I don't suppose I'm right") introduces a playful humility, contrasting with the rigidity of adult expectations.

Themes

1. Friendship as a Shield Against Judgment

The central theme of The Friend is the redemptive power of companionship. The speaker’s fear of being "thought silly" reveals a vulnerability to external judgment, a universal human concern. Pooh’s presence transforms this anxiety—his tentative suggestions ("I don’t suppose I’m right") create a shared space where mistakes are harmless. The final lines—

"And then it doesn't matter what the answer ought to be,

'Cos if he's right, I'm Right, and if he's wrong, it isn't Me."

—epitomize friendship as a buffer against shame. The capitalization of "Right" and "Me" suggests that correctness is less important than solidarity.

2. The Illusion of Certainty

The poem critiques the arbitrary nature of knowledge. The questions posed ("Dates and Pounds-and-ounces") are trivial, yet the child perceives them as high-stakes. Pooh’s ambivalence ("I don’t suppose I’m right") mirrors the child’s self-doubt, but together, they reframe uncertainty as acceptable. This aligns with Milne’s broader skepticism toward dogmatism—his works often celebrate intuition over rigid logic.

3. Childhood vs. Adulthood

The poem contrasts the child’s imaginative world with the adult realm of fixed answers. Adults "are always asking things," demanding precision, while the child and Pooh navigate knowledge playfully. This dichotomy reflects Milne’s belief in preserving childlike wonder against the pressures of growing up—a theme also evident in Now We Are Six and The House at Pooh Corner.

Emotional Impact

The poem’s charm lies in its gentle humor and profound emotional truth. Readers—both children and adults—recognize the fear of failure and the relief of having a companion who shares the burden. The closing lines, with their clever logic, evoke both laughter and tenderness. The child’s reasoning is delightfully flawed—if Pooh is wrong, "it isn't Me"—yet this flawed logic is emotionally sound. The poem reassures us that friendship mitigates the sting of imperfection.

Comparative Analysis

Milne’s portrayal of friendship in The Friend can be compared to Wordsworth’s We Are Seven, where a child’s unwavering belief in the presence of deceased siblings defies adult rationality. Both poems validate the child’s perspective as emotionally truthful, even if factually incorrect. Similarly, Lewis Carroll’s Alice books juxtapose childish logic against absurd adult rigidity, though Carroll’s tone is more satirical, whereas Milne’s is affectionate.

Within Milne’s own oeuvre, The Friend echoes the dynamic between Christopher Robin and Pooh, where the bear’s simplicity is a source of comfort rather than frustration. Unlike traditional didactic children’s verse (e.g., Isaac Watts’ Divine Songs), Milne’s poem does not moralize; instead, it celebrates the emotional logic of childhood.

Biographical and Philosophical Insights

Milne’s relationship with his son, Christopher Robin, undoubtedly influenced The Friend. The real Christopher Robin’s stuffed animals, including Pooh, were companions in his solitary play, and Milne’s poems often immortalized these bonds. The poem can be read as a tribute to the solace children find in imaginary friendships—a theme that resonated with post-war audiences seeking comfort.

Philosophically, the poem aligns with existentialist ideas of shared meaning. In a world where answers are arbitrary ("Sixpence or A Hundred Inches Long"), the speaker and Pooh create their own truth through mutual affirmation. This mirrors Martin Buber’s I-Thou relationship, where genuine connection transcends objective reality.

Conclusion

The Friend is a miniature masterpiece that encapsulates Milne’s genius for blending whimsy with emotional depth. Through its playful tone, subtle irony, and heartfelt themes, the poem elevates childhood friendship to a philosophical stance—one where loyalty outweighs correctness, and shared uncertainty becomes a form of wisdom. In an era obsessed with measurable knowledge, Milne’s poem remains a tender reminder that sometimes, the best answers are the ones we discover together.

Ultimately, The Friend is not just about a boy and his bear; it is about the universal human need for companionship in the face of life’s unanswerable questions. And in that, it speaks across generations, offering solace to anyone who has ever whispered to a friend, "I don’t suppose I’m right," and found comfort in the reply.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!