January, 1795

Mary Robinson

1757 to 1800

Pavement slipp’ry, people sneezing,

Lords in ermine, beggars freezing;

Titled gluttons dainties carving,

Genius in a garret starving.

Lofty mansions, warm and spacious;

Courtiers cringing and voracious;

Misers scarce the wretched heeding;

Gallant soldiers fighting, bleeding.

Wives who laugh at passive spouses;

Theatres, and meeting-houses;

Balls, where simp’ring misses languish;

Hospitals, and groans of anguish.

Arts and sciences bewailing;

Commerce drooping, credit failing;

Placemen mocking subjects loyal;

Separations, weddings royal.

Authors who can’t earn a dinner;

Many a subtle rogue a winner;

Fugitives for shelter seeking;

Misers hoarding, tradesmen breaking.

Taste and talents quite deserted;

All the laws of truth perverted;

Arrogance o’er merit soaring;

Merit silently deploring.

Ladies gambling night and morning;

Fools the works of genius scorning;

Ancient dames for girls mistaken,

Youthful damsels quite forsaken.

Some in luxury delighting;

More in talking than in fighting;

Lovers old, and beaux decrepid;

Lordlings empty and insipid.

Poets, painters, and musicians;

Lawyers, doctors, politicians:

Pamphlets, newspapers, and odes,

Seeking fame by diff’rent roads.

Gallant souls with empty purses;

Gen’rals only fit for nurses;

School-boys, smit with martial spirit,

Taking place of vet’ran merit.

Honest men who can’t get places,

Knaves who shew unblushing faces;

Ruin hasten’d, peace retarded;

Candor spurn’d, and art rewarded.

Mary Robinson's January, 1795

Introduction

Mary Robinson's poem "January, 1795" presents a scathing critique of late 18th-century English society, offering a panoramic view of urban life that spans from the opulent to the destitute. Through a series of vivid vignettes, Robinson constructs a complex tapestry of social commentary, exposing the stark contrasts and moral contradictions of her time. This analysis will delve into the poem's structure, themes, and literary devices, examining how Robinson's work serves as both a snapshot of a historical moment and a timeless indictment of societal inequities.

Structure and Form

The poem's structure is immediately striking, consisting of twenty-two couplets of rhyming eight-syllable lines. This tight, consistent form creates a rhythmic cadence that propels the reader through a rapid-fire succession of images. The regularity of the meter contrasts sharply with the chaotic scenes described, heightening the sense of discord and instability in the society Robinson portrays.

Each couplet presents a self-contained observation, often juxtaposing two related or contrasting elements of society. This paratactic structure, where clauses are placed side by side without coordinating conjunctions, creates a staccato effect that mimics the fragmented nature of urban experience. The cumulative impact of these brief, pointed observations builds to form a comprehensive critique of English society.

Thematic Analysis

Social Inequality

At the heart of Robinson's poem lies a biting commentary on social inequality. The opening lines immediately establish this theme: "Pavement slipp'ry, people sneezing, / Lords in ermine, beggars freezing." The juxtaposition of "Lords" and "beggars" underscores the vast disparity between the upper and lower classes, while the shared experience of the "slipp'ry" pavement and "sneezing" suggests a common humanity that transcends social boundaries.

Throughout the poem, Robinson continues to highlight these inequalities: "Lofty mansions, warm and spacious; / Courtiers cringing and voracious; / Misers scarce the wretched heeding." The contrast between the comfort of the wealthy and the suffering of the poor is stark and unforgiving. The poet's use of alliteration in "cringing" and "voracious" emphasizes the sycophantic and greedy nature of those in power.

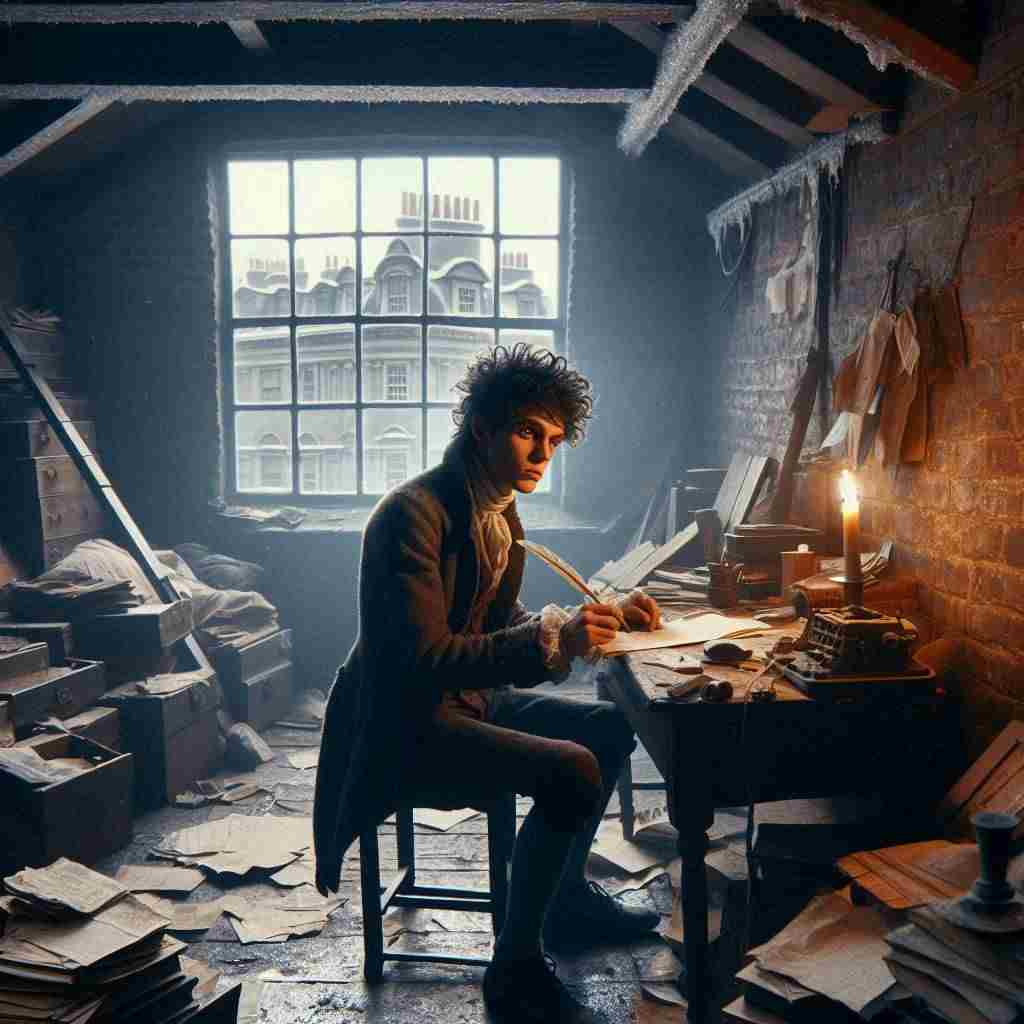

The Plight of Artists and Intellectuals

Robinson, herself a poet and actress, pays particular attention to the struggles of artists and intellectuals in a society that undervalues their contributions. The lines "Genius in a garret starving" and "Authors who can't earn a dinner" paint a bleak picture of the creative class's economic hardships. The phrase "Arts and sciences bewailing" suggests a broader cultural decline, where intellectual pursuits are neglected or actively disdained.

This theme is further developed in the couplet "Taste and talents quite deserted; / All the laws of truth perverted," implying a society that has lost its appreciation for genuine merit and artistic value. The line "Fools the works of genius scorning" directly criticizes those who fail to recognize or respect intellectual and creative achievements.

Moral Decay and Hypocrisy

Throughout the poem, Robinson exposes the moral bankruptcy of various societal institutions and practices. The juxtaposition of "Theatres, and meeting-houses" suggests a blurring of the lines between entertainment and religion, while "Balls, where simp'ring misses languish; / Hospitals, and groans of anguish" contrasts frivolous social gatherings with genuine human suffering.

The poet takes aim at political corruption in lines such as "Placemen mocking subjects loyal" and "Knaves who shew unblushing faces," revealing a system where dishonesty and self-interest triumph over integrity and public service. The gambling habits of the upper class ("Ladies gambling night and morning") are presented as symptomatic of a broader moral decline.

Gender and Age

Robinson, known for her proto-feminist views, incorporates subtle commentary on gender roles and societal expectations. The line "Wives who laugh at passive spouses" subverts traditional marital dynamics, while "Ancient dames for girls mistaken, / Youthful damsels quite forsaken" critiques society's obsession with youth and its impact on women of different ages.

The portrayal of men is equally unflattering, with "Lovers old, and beaux decrepid; / Lordlings empty and insipid" suggesting a lack of substance and virility among the upper-class male population.

Literary Devices and Techniques

Irony and Satire

Robinson employs irony throughout the poem to highlight the absurdities and contradictions of her society. The juxtaposition of "Gallant soldiers fighting, bleeding" with "More in talking than in fighting" exposes the gap between heroic ideals and the reality of those in power. Similarly, "Gen'rals only fit for nurses" uses irony to critique the competence of military leadership.

The satirical tone is maintained through the use of deliberately understated language to describe outrageous situations, such as "Misers scarce the wretched heeding," where the poet's restraint in expression serves to heighten the reader's sense of moral outrage.

Imagery and Sensory Details

Despite the poem's rapid-fire structure, Robinson manages to incorporate vivid imagery and sensory details that bring her observations to life. The "Pavement slipp'ry" and "people sneezing" in the opening line immediately place the reader in a tangible, physical environment. The "groans of anguish" from hospitals create an auditory dimension that contrasts sharply with the visual imagery of "Balls, where simp'ring misses languish."

Alliteration and Sound Patterns

Robinson employs alliteration and other sound patterns to enhance the poem's musicality and emphasize key concepts. Examples include "Commerce drooping, credit failing," where the repeated 'c' sound underscores the interconnected nature of economic woes, and "Separations, weddings royal," where the 's' and 'w' sounds link personal and public spheres of marital discord and celebration.

Historical Context

"January, 1795" was written during a tumultuous period in European history. The French Revolution had sent shockwaves throughout the continent, and England was embroiled in war with France. The poem's references to "Fugitives for shelter seeking" may allude to French émigrés fleeing the Revolution, while "Gallant soldiers fighting, bleeding" likely refers to the ongoing conflict.

The economic instability of the time is reflected in lines such as "Commerce drooping, credit failing," which speak to the financial challenges faced by England during wartime. The mention of "Separations, weddings royal" may refer to the controversial marriage of the Prince of Wales (later George IV) to Caroline of Brunswick in 1795, a union that was quickly marked by separation and scandal.

Conclusion

Mary Robinson's "January, 1795" stands as a masterful example of social critique in poetic form. Through its innovative structure, vivid imagery, and incisive observations, the poem offers a comprehensive indictment of late 18th-century English society. Robinson's ability to capture the complexities of urban life in a series of brief, powerful vignettes demonstrates her keen eye for social dynamics and her skill as a poet.

The work's enduring relevance lies in its exploration of themes that continue to resonate in contemporary society: inequality, the struggle of artists and intellectuals, political corruption, and the tension between appearance and reality. By holding a mirror to the contradictions and injustices of her time, Robinson challenges readers to reflect on the persistent issues that plague modern urban life.

Moreover, "January, 1795" showcases Robinson's unique voice as a female poet in a male-dominated literary landscape. Her unflinching critique of societal norms and power structures marks her as an important precursor to later feminist writers and social reformers.

In its brevity and precision, the poem achieves a remarkable depth of social analysis, proving that great literature need not be lengthy to be profound. Robinson's work serves as a testament to the power of poetry to encapsulate complex social realities and to inspire critical reflection on the world we inhabit.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!