When I am dead, my dearest

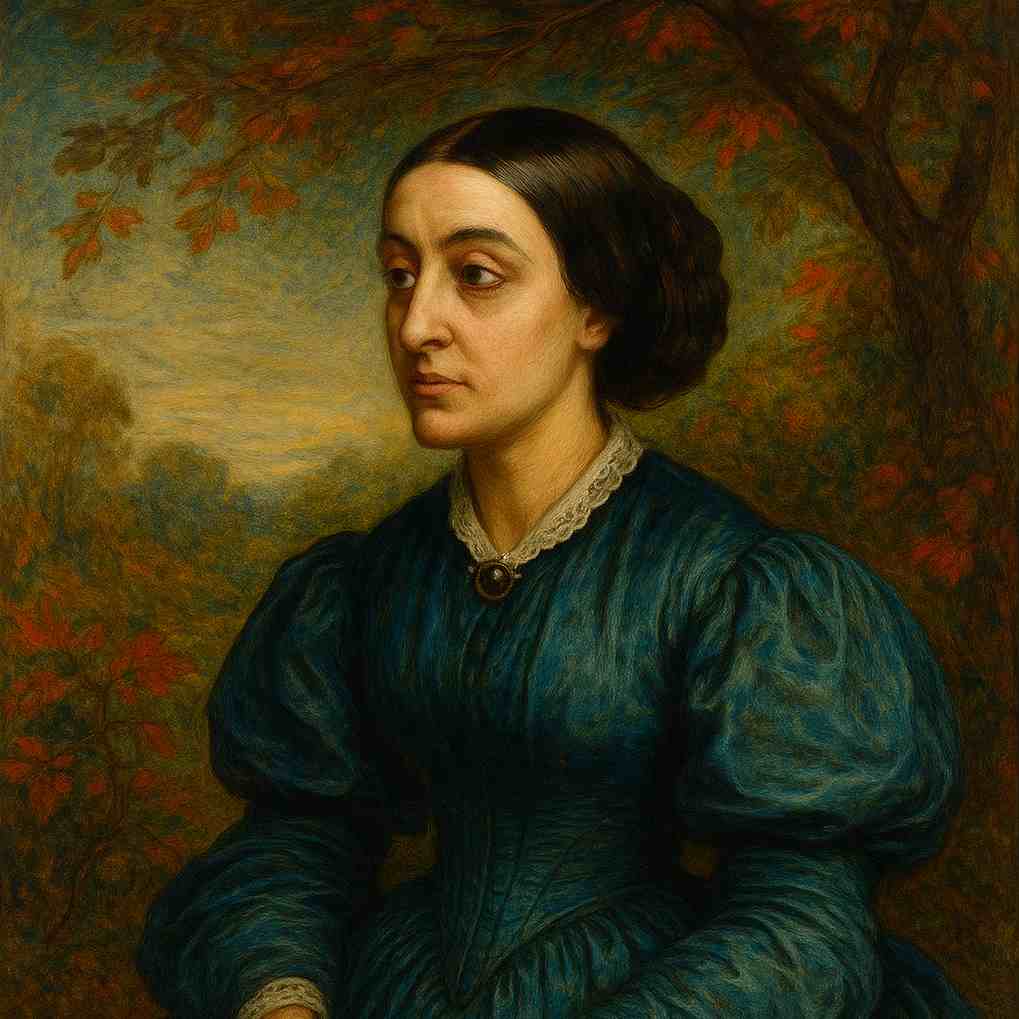

Christina Rossetti

1830 to 1894

When I am dead, my dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me;

Plant thou no roses at my head,

Nor shady cypress tree:

Be the green grass above me

With showers and dewdrops wet;

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I shall not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

Christina Rossetti's When I am dead, my dearest

Christina Rossetti's poem "When I am dead, my dearest" is a poignant exploration of death, memory, and the relationship between the living and the deceased. Through its carefully crafted structure and evocative imagery, Rossetti challenges conventional notions of grief and remembrance, offering instead a nuanced perspective on the nature of existence beyond death.

The poem is composed of two octaves, each following an ABCBDEFE rhyme scheme. This structure lends a musical quality to the verse, echoing the reference to "sad songs" in the second line. The regularity of the form contrasts with the unconventional sentiments expressed, creating a tension that underscores the poem's complex themes.

Rossetti opens with a direct address to a loved one, immediately establishing an intimate tone. The speaker's instructions to the addressee are striking in their rejection of traditional mourning practices. By urging "Sing no sad songs for me" and "Plant thou no roses at my head, / Nor shady cypress tree," the speaker subverts expectations of how the dead should be remembered. These lines challenge the Victorian cult of mourning, which often emphasized elaborate rituals and memorials.

Instead of ornate remembrances, the speaker desires simplicity: "Be the green grass above me / With showers and dewdrops wet." This imagery evokes a sense of natural cycles and regeneration, suggesting that death is part of a larger process rather than an end to be lamented. The emphasis on nature over human-made memorials also hints at a desire to return to and become one with the natural world.

The notion of memory is central to the poem, and Rossetti's treatment of it is particularly nuanced. The lines "And if thou wilt, remember, / And if thou wilt, forget" present remembrance not as an obligation, but as a choice. This radical idea liberates both the deceased and the living from the burden of perpetual grief. It suggests that the speaker values the addressee's well-being and freedom over being remembered, a sentiment that recurs in the poem's final lines.

The second stanza shifts perspective, as the speaker contemplates their own state after death. The repeated use of "I shall not" emphasizes the cessation of sensory experiences: seeing shadows, feeling rain, hearing the nightingale. This litany of negations might initially seem to paint a bleak picture of death. However, the tone is not one of despair but rather of calm acceptance.

The nightingale, traditionally a symbol of melancholy and unrequited love in poetry, is described as singing "as if in pain." The speaker's inability to hear this sorrowful song after death could be interpreted as a release from earthly suffering. This reading is supported by the dreamlike state described in the final quatrain, where the speaker exists in a twilight "That doth not rise nor set." This timeless, liminal space suggests a form of existence beyond physical reality.

The poem concludes with a parallel to the first stanza's meditation on memory: "Haply I may remember, / And haply may forget." The use of "haply," meaning "perhaps" or "by chance," introduces an element of uncertainty to the afterlife. This ambiguity extends the poem's earlier theme of choice in remembrance to the deceased themselves. The speaker acknowledges that they too might forget, placing them on equal footing with the living addressee.

Rossetti's poem, through its rejection of conventional mourning and its embrace of uncertainty, offers a surprisingly modern perspective on death. It suggests that true love and respect for the deceased might involve letting go rather than clinging to memories. The poem's gentle tone and natural imagery soften what might otherwise be perceived as a stark message, creating a work that is both comforting and thought-provoking.

In conclusion, "When I am dead, my dearest" is a masterful exploration of death that challenges readers to reconsider their assumptions about grief, memory, and the relationship between the living and the dead. Rossetti's skillful use of form, imagery, and repetition creates a poem that is at once accessible and profound, offering insights that remain relevant to contemporary discussions of mortality and remembrance.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!