The Past

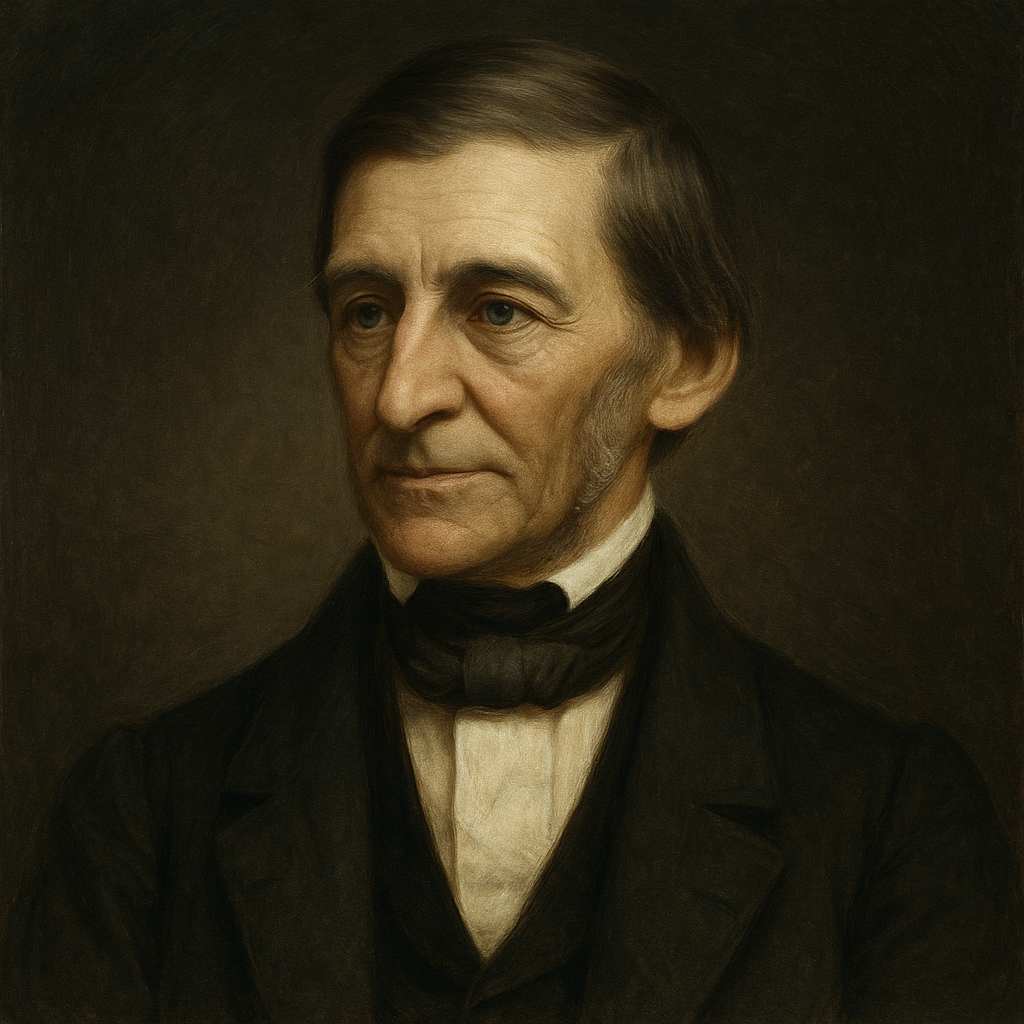

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803 to 1882

The debt is paid,

The verdict said,

The Furies laid,

The plague is stayed.

All fortunes made;

Turn the key and bolt the door,

Sweet is death forevermore.

Nor haughty hope, nor swart chagrin,

Nor murdering hate, can enter in.

All is now secure and fast;

Not the gods can shake the Past;

Flies-to the adamantine door

Bolted down forevermore.

None can reënter there,—

No thief so politic,

No Satan with a royal trick

Steal in by window, chink, or hole,

To bind or unbind, add what lacked,

Insert a leaf, or forge a name,

New-face or finish what is packed,

Alter or mend eternal Fact.

Ralph Waldo Emerson's The Past

Introduction

Ralph Waldo Emerson's poem "The Past" stands as a profound meditation on the immutability of history and the finality of past events. This piece, characteristic of Emerson's transcendentalist philosophy, delves into the complex relationship between time, memory, and human experience. Through a careful analysis of its structure, imagery, and thematic elements, we can uncover the layers of meaning embedded within this deceptively simple work.

Structure and Form

The poem consists of 22 lines, primarily composed in rhyming couplets with occasional deviations. This structure lends itself to a sense of finality and closure, mirroring the theme of the poem itself. The irregular meter, alternating between short, punchy lines and longer, more flowing ones, creates a rhythmic tension that underscores the poem's exploration of the relationship between past and present.

Emerson's use of enjambment in lines such as "Turn the key and bolt the door, / Sweet is death forevermore" serves to create a sense of continuity and inevitability, reinforcing the idea that the past flows inexorably into the present and future.

Imagery and Symbolism

The poem is rich with vivid imagery, particularly centered around the concept of closure and finality. The recurring motif of locked doors and bolts ("Turn the key and bolt the door," "Flies-to the adamantine door / Bolted down forevermore") serves as a powerful metaphor for the inaccessibility of the past. This imagery evokes a sense of both security and imprisonment, suggesting that while the past may be safely contained, it is also beyond our reach to alter or revisit.

Emerson's use of personification in lines such as "Nor haughty hope, nor swart chagrin, / Nor murdering hate, can enter in" brings abstract concepts to life, emphasizing the power of the past to resist emotional manipulation or reinterpretation. The anthropomorphization of these feelings creates a dramatic tension, as if the past were a fortress besieged by human emotions seeking entry.

The "adamantine door" is a particularly potent symbol, drawing on the classical notion of adamant as an unbreakable substance. This image reinforces the poem's central theme of the past's inviolability, presenting it as a realm beyond human interference.

Thematic Analysis

At its core, "The Past" grapples with the concept of historical determinism and the human desire to alter or escape from the consequences of past actions. The opening lines, "The debt is paid, / The verdict said," immediately establish a tone of finality and judgment. This judicial metaphor suggests that the past serves as both record and arbiter of human actions.

Emerson's transcendentalist philosophy is evident in the poem's treatment of time and eternity. The line "Not the gods can shake the Past" elevates the immutability of history to a cosmic level, suggesting that even divine powers are bound by the flow of time. This concept aligns with transcendentalist ideas about the interconnectedness of all things and the presence of the divine in the natural order.

The poem also explores the psychological implications of an unchangeable past. The mention of "thief," "Satan," and attempts to "bind or unbind, add what lacked, / Insert a leaf, or forge a name" speaks to the human impulse to revise history. These lines can be read as a commentary on the futility of self-deception or historical revisionism, asserting that no matter how clever or powerful one may be, the fundamental facts of the past remain beyond alteration.

Language and Tone

Emerson's diction in "The Past" is characterized by its blend of archaic and contemporary language. Words like "chagrin" and "reënter" (with its distinctive diaeresis) lend an air of formality and timelessness to the piece. This linguistic choice serves to underscore the poem's themes of eternity and immutability.

The tone of the poem shifts subtly throughout its progression. The opening lines carry a sense of finality and perhaps relief ("The plague is stayed"), while the middle section introduces a note of defiance against those who would seek to change the past. The concluding lines, with their emphasis on the impossibility of altering "eternal Fact," strike a tone of resigned acceptance, perhaps even awe at the unyielding nature of history.

Philosophical Implications

"The Past" invites reflection on several philosophical questions. It challenges the reader to consider the nature of free will in a universe where the past is immutable. If, as the poem suggests, we cannot alter what has already occurred, how does this affect our understanding of choice and responsibility in the present?

Moreover, the poem raises questions about the nature of truth and reality. The assertion that one cannot "Alter or mend eternal Fact" implies a belief in objective historical truth, a concept that has been heavily debated in both philosophy and historiography. Emerson's stance here seems to align with a realist philosophical perspective, asserting the existence of an objective reality independent of human perception or desire.

Literary Context

To fully appreciate "The Past," it is crucial to consider its place within Emerson's broader body of work and the literary context of 19th-century American poetry. The poem's themes resonate with Emerson's essays, particularly "Self-Reliance" and "Experience," which explore the individual's relationship with time, nature, and society.

The poem also reflects the preoccupations of the American Renaissance, a period marked by a search for a distinctly American literary voice and an exploration of the nation's history and identity. Emerson's meditation on the past can be read as part of this broader cultural project, grappling with questions of national memory and the role of history in shaping American consciousness.

Conclusion

Ralph Waldo Emerson's "The Past" emerges as a complex and nuanced exploration of time, memory, and human nature. Through its intricate interplay of form, imagery, and philosophical inquiry, the poem challenges readers to confront the immutability of history and its implications for our understanding of self and society.

The poem's enduring relevance lies in its ability to provoke reflection on fundamental questions of existence: How do we reconcile ourselves with the unalterable nature of past events? What is the relationship between memory, truth, and identity? In an age of increasing historical revisionism and debates over collective memory, Emerson's assertion of an inviolable past takes on new significance.

Ultimately, "The Past" stands as a testament to Emerson's poetic craft and philosophical depth. It invites repeated reading and interpretation, each encounter revealing new layers of meaning and prompting fresh contemplation of our place in the vast tapestry of time.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!