Summer Sun

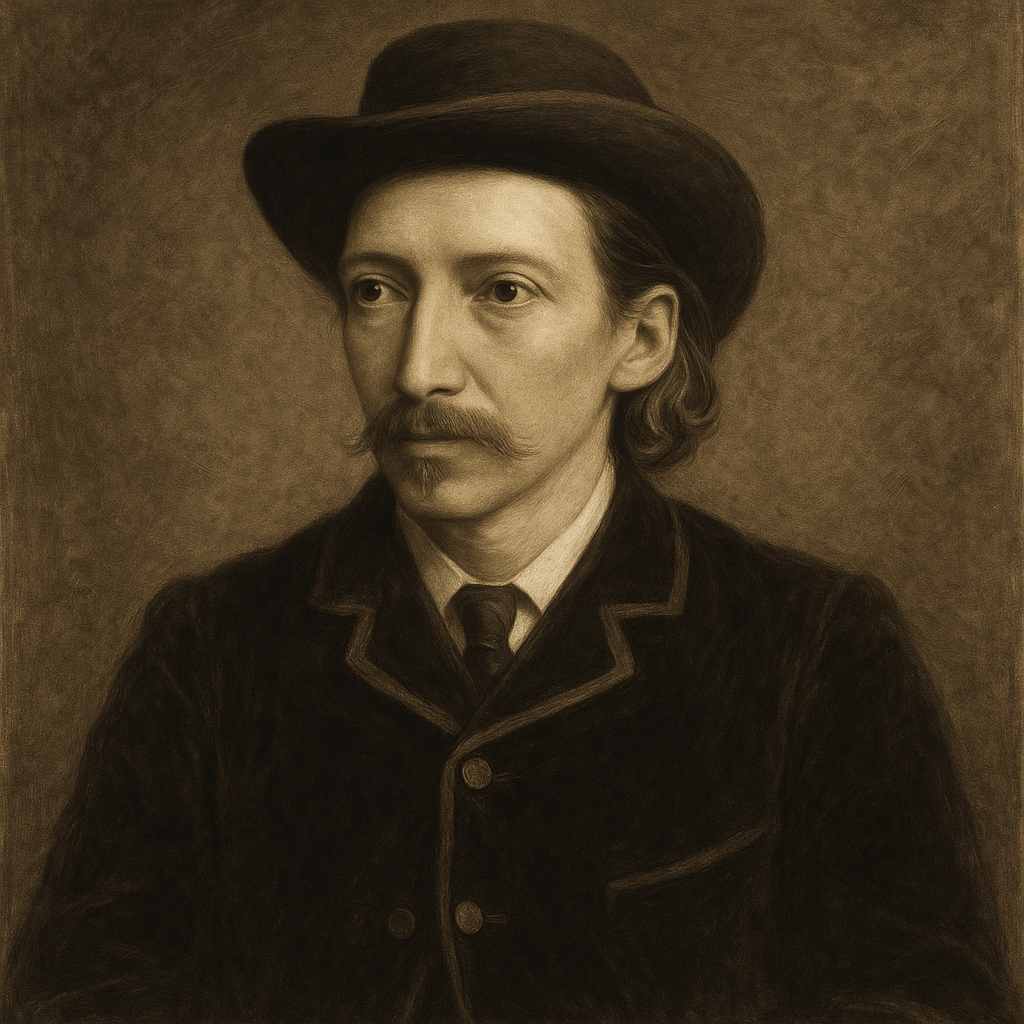

Robert Louis Stevenson

1850 to 1894

Great is the sun, and wide he goes

Through empty heaven without repose;

And in the blue and glowing days

More thick than rain he showers his rays.

Though closer still the blinds we pull

To keep the shady parlour cool,

Yet he will find a chink or two

To slip his golden fingers through.

The dusty attic, spider-clad,

He, through the keyhole, maketh glad;

And through the broken edge of tiles

Into the laddered hay-loft smiles.

Meantime his golden face around

He bares to all the garden ground,

And sheds a warm and glittering look

Among the ivy's inmost nook.

Above the hills, along the blue,

Round the bright air with footing true,

To please the child, to paint the rose,

The gardener of the World, he goes.

Robert Louis Stevenson's Summer Sun

Introduction

Robert Louis Stevenson's poem "Summer Sun" presents a vivid and enchanting portrayal of the sun's pervasive presence during the height of summer. This seemingly simple poem, with its playful rhythm and imagery, belies a deeper exploration of the relationship between humanity, nature, and the cosmic forces that govern our world. Through a careful analysis of the poem's structure, language, and thematic elements, we can uncover the rich tapestry of meaning woven by Stevenson, a master of both children's literature and adult fiction.

Structure and Form

The poem consists of five quatrains, each following an ABAB rhyme scheme. This regular structure, combined with the poem's iambic tetrameter, creates a rhythmic quality that mirrors the steady, relentless progress of the sun across the sky. The consistency of the form stands in contrast to the sun's ability to penetrate and transform various spaces, suggesting a tension between order and chaos, containment and expansion.

Stevenson's choice of quatrains is particularly apt, as the four-line stanzas echo the four cardinal directions, reinforcing the idea of the sun's omnipresence. The alternating rhyme scheme (ABAB) creates a sense of movement and progression, mirroring the sun's journey and its interaction with different elements of the landscape.

Imagery and Personification

One of the most striking aspects of "Summer Sun" is Stevenson's masterful use of personification. The sun is not merely a celestial body but an active, almost sentient force. This anthropomorphization is evident from the opening lines: "Great is the sun, and wide he goes / Through empty heaven without repose." The use of the pronoun "he" immediately imbues the sun with a personality, while the phrase "without repose" suggests a tireless, driven nature.

Throughout the poem, the sun is depicted as having agency and intent. It "showers his rays," finds "a chink or two / To slip his golden fingers through," and "maketh glad" the dusty attic. This personification serves multiple purposes. It makes the sun more relatable and understandable to the reader, particularly to children, for whom the poem may have been initially intended. It also elevates the sun to the status of a character, allowing Stevenson to explore the relationship between this cosmic entity and the earthly realm it illuminates.

The imagery Stevenson employs is rich and varied, appealing to multiple senses. The visual imagery is particularly strong, with phrases like "blue and glowing days," "golden fingers," and "golden face" creating a vivid picture of summer brightness. The tactile sensation of warmth is evoked through expressions like "sheds a warm and glittering look." This multisensory approach immerses the reader in the experience of a summer day, making the poem not just a description but an evocation of the season.

Thematic Analysis

At its core, "Summer Sun" is an exploration of the interplay between light and darkness, openness and enclosure, and the natural world and human habitation. The sun, as the poem's protagonist, is portrayed as a benevolent invader, penetrating the barriers humans erect against it. This invasion, however, is not depicted as hostile but as life-giving and joy-bringing.

The poem progresses through various spaces, moving from the vast expanse of the "empty heaven" to increasingly enclosed areas: the "shady parlour," the "dusty attic," and the "laddered hay-loft." This progression creates a sense of the sun's persistence and its ability to reach even the most secluded corners. It also serves as a metaphor for the inescapable nature of joy and vitality, suggesting that no matter how we might try to shut ourselves away, life and light will find a way to reach us.

There's a subtle critique of human behavior embedded in the poem. The line "Though closer still the blinds we pull / To keep the shady parlour cool" hints at humanity's tendency to shut out the natural world, seeking comfort in artificial environments. Yet the sun's ability to find "a chink or two" suggests the futility of this effort and perhaps gently chides the reader for attempting to exclude the beauty and warmth of nature.

The poem also touches on themes of transformation and renewal. The sun's interaction with different spaces changes them: the dusty attic is made glad, the hay-loft smiles, the garden ground is bared to the sun's face. This transformative power extends to living things as well, as the sun goes "To please the child, to paint the rose." Here, Stevenson links the sun's influence on the natural world with its effect on human emotion, suggesting a deep interconnectedness between cosmic forces, nature, and human experience.

Literary Devices and Technique

Stevenson's mastery of language is evident in his use of alliteration and assonance throughout the poem. Phrases like "glowing days" and "golden fingers" create a sonic texture that enhances the poem's sensory appeal. The repeated use of the long 'o' sound in words like "goes," "repose," "glowing," and "golden" creates a sense of expansiveness that mirrors the sun's reach.

The poet also employs enjambment effectively, allowing thoughts to flow across line breaks. This technique creates a sense of continuity and movement, reinforcing the idea of the sun's ceaseless journey. For example, the lines "Yet he will find a chink or two / To slip his golden fingers through" use enjambment to mimic the action being described, with the thought slipping through the line break just as the sun's rays slip through the chinks.

Stevenson's diction is carefully chosen to create a balance between accessibility and poetic beauty. While the vocabulary is relatively simple, making the poem suitable for readers of various ages, the combinations of words create vivid and sometimes unexpected images. The phrase "the dusty attic, spider-clad" is particularly effective, conjuring a detailed picture with just a few words and linking the mundane (dust) with the slightly mysterious or frightening (spiders) before showing how the sun's presence transforms even this neglected space.

Cultural and Literary Context

To fully appreciate "Summer Sun," it's important to consider its place within Stevenson's body of work and the broader context of Victorian literature. Stevenson, known for works like "Treasure Island" and "Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde," often explored themes of duality and the interplay between light and dark, both literally and metaphorically. "Summer Sun" can be seen as a lighter exploration of these themes, focusing on the positive, life-affirming aspects of light.

The poem also reflects the Victorian fascination with nature and the changing relationship between humans and the natural world in an increasingly industrialized society. The sun's persistence in entering human-made spaces can be read as a reassertion of nature's primacy, a common theme in Romantic and post-Romantic poetry.

Furthermore, the poem's accessibility and its focus on a simple natural phenomenon align with the Victorian interest in children's literature and the belief in the instructive power of nature. Stevenson, like many of his contemporaries, saw value in creating works that could speak to both children and adults, embedding deeper meanings within seemingly simple verses.

Conclusion

"Summer Sun" by Robert Louis Stevenson is a deceptively simple poem that rewards close reading and analysis. Through its structure, imagery, and thematic content, it offers a meditation on the power of nature, the human relationship with the cosmic and natural world, and the transformative potential of light and warmth. Stevenson's skillful use of personification, sensory imagery, and poetic devices creates a work that is at once accessible and profound, capable of delighting younger readers with its rhythmic charm while offering deeper insights to those who probe its subtle complexities.

The poem serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of all things, from the vast movements of celestial bodies to the small details of a dusty attic or a blooming rose. In its celebration of the sun's journey "To please the child, to paint the rose," Stevenson presents a vision of a world where beauty, joy, and vitality are ever-present, waiting only for us to open ourselves to their influence. As such, "Summer Sun" stands as a testament to Stevenson's poetic craftsmanship and his ability to distill profound truths into seemingly simple verses, offering readers of all ages a moment of reflection on the wonders that surround us daily.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!