Winter Rain

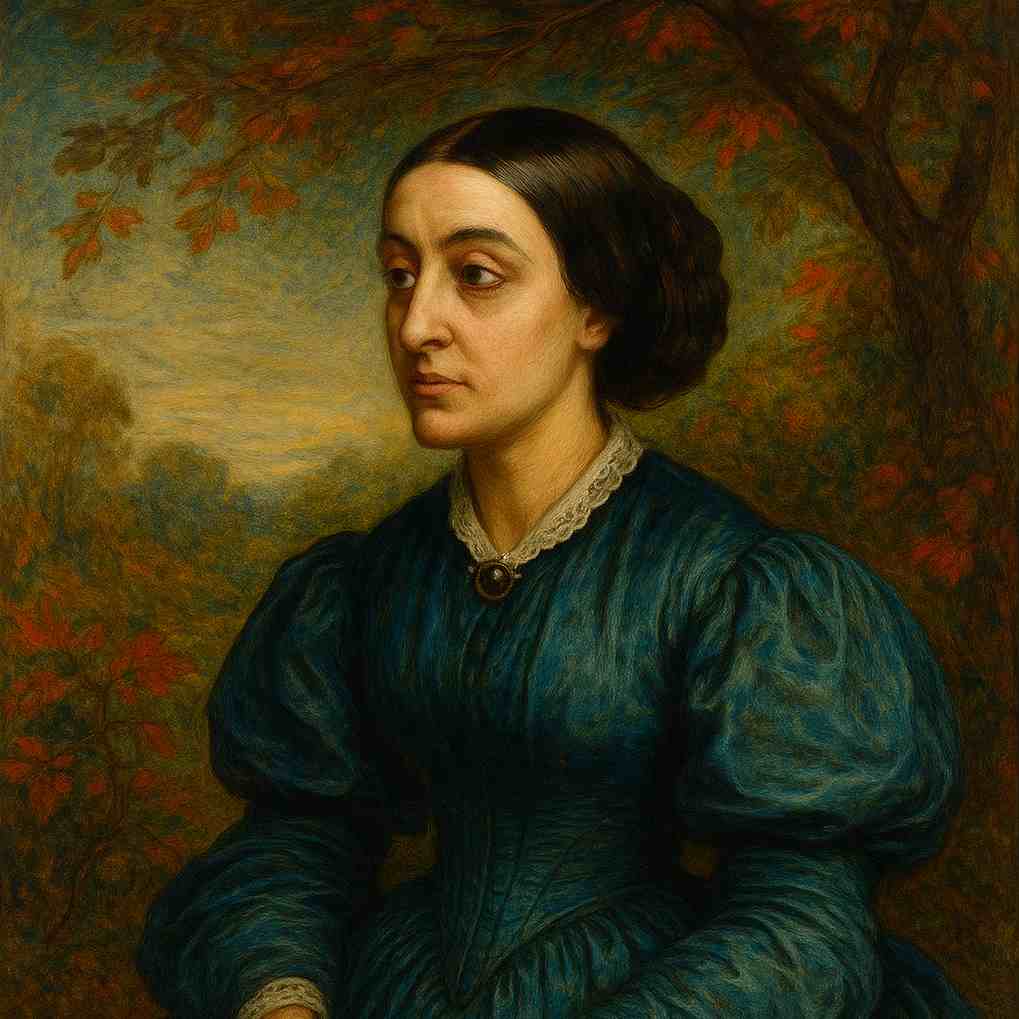

Christina Rossetti

1830 to 1894

Every valley drinks,

Every dell and hollow:

Where the kind rain sinks and sinks,

Green of Spring will follow.

Yet a lapse of weeks

Buds will burst their edges,

Strip their wool-coats, glue-coats, streaks,

In the woods and hedges;

Weave a bower of love

For birds to meet each other,

Weave a canopy above

Nest and egg and mother.

But for fattening rain

We should have no flowers,

Never a bud or leaf again

But for soaking showers;

Never a mated bird

In the rocking tree-tops,

Never indeed a flock or herd

To graze upon the lea-crops.

Lambs so woolly white,

Sheep the sun-bright leas on,

They could have no grass to bite

But for rain in season.

We should find no moss

In the shadiest places,

Find no waving meadow-grass

Pied with broad-eyed daisies;

But miles of barren sand,

With never a son or daughter,

Not a lily on the land,

Or lily on the water.

Christina Rossetti's Winter Rain

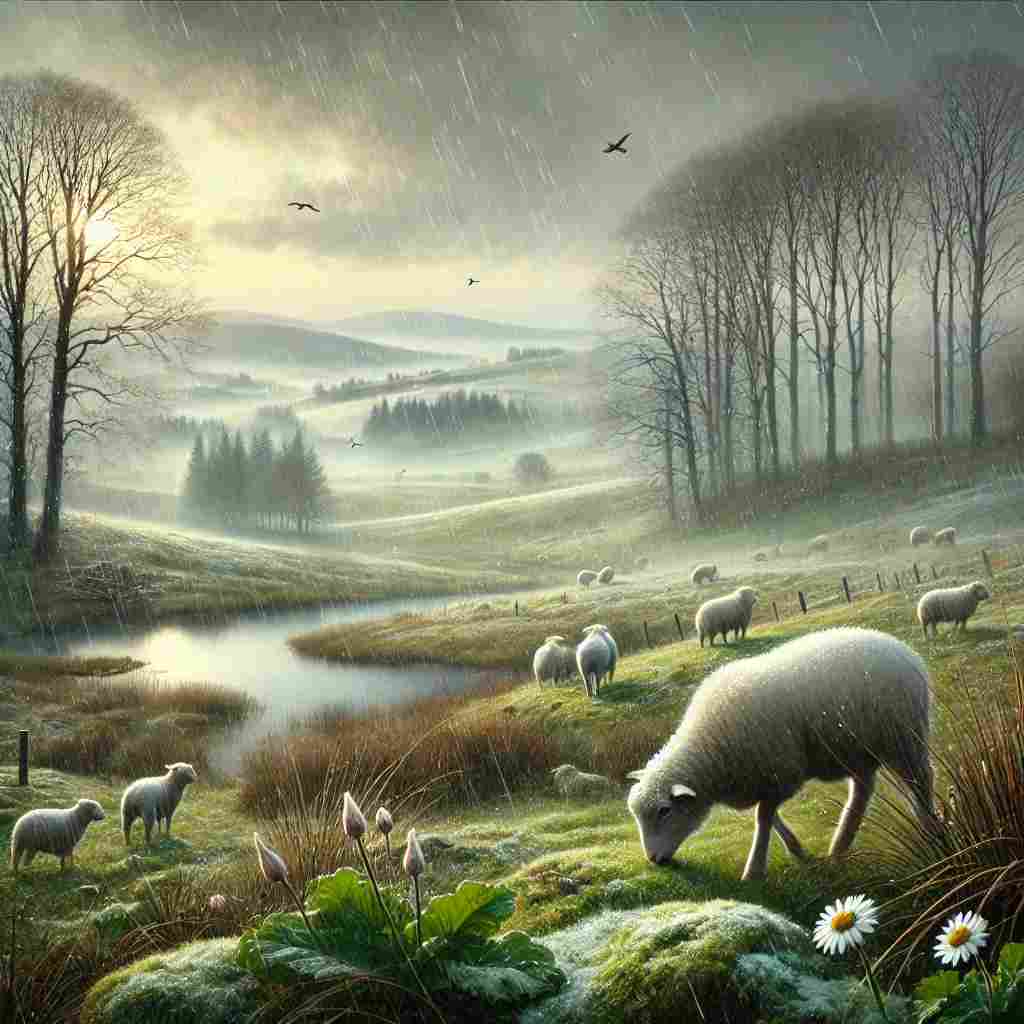

Christina Rossetti's "Winter Rain" presents a meditation on the life-giving power of rain and the seasonal cycles of growth it initiates. Through the poem, Rossetti captures the quiet beauty and necessity of winter rains, describing their role in nourishing the natural world and supporting the seasonal transformation from barren winter to vibrant spring. Using vivid imagery and a gentle rhythm, she celebrates the interconnectedness of nature, drawing attention to rain’s essential, often overlooked role in the renewal of life.

Stanza One: The Promise of Growth

The poem opens with an image of the rain sinking deeply into “every valley” and “every dell and hollow.” Rossetti’s repetition of “every” emphasizes the rain’s reach, suggesting that this nurturing force touches all parts of the landscape indiscriminately. Rain, in Rossetti’s portrayal, is not merely a weather phenomenon but a kind and nurturing presence: “Where the kind rain sinks and sinks, / Green of Spring will follow.” This “kind rain” is personified as gentle and benevolent, setting the stage for the rebirth of the landscape. The promise that “Green of Spring will follow” adds a hopeful tone, highlighting rain as the essential precursor to the life and beauty that Spring will bring.

Stanza Two: Emerging Life and Renewal

The second stanza shifts to the idea of buds that will “burst their edges,” shedding their “wool-coats” and “glue-coats” in preparation for new growth. Here, Rossetti employs tactile imagery to depict nature's transformation. The phrase “wool-coats, glue-coats” suggests the coverings that protect plant life through winter, symbolizing the dormant energy waiting to emerge. The specific, almost playful language captures the wonder of nature's self-renewal: as winter recedes, the buds gradually unveil themselves in the woods and hedges, driven by the rain’s promise of abundance. This stanza portrays growth as both tender and active, evoking the careful unfolding of leaves and flowers as they come into being.

Stanza Three: The Bower of Love and Nurture

Rossetti introduces a “bower of love” in the third stanza, where birds will “meet each other.” This image of a natural shelter hints at themes of companionship and fertility as the natural world prepares for the arrival of new life. The “canopy above / Nest and egg and mother” invokes a vision of protection and nurturing, underscoring how the rain indirectly enables not only the growth of flora but also the continuation of fauna. This stanza thus suggests a vision of harmony and cooperation within nature, where rain is the unseen facilitator of life’s cycles, making room for reproduction and shelter.

Stanza Four: The Indispensability of Rain

In this stanza, Rossetti emphasizes that “for fattening rain / We should have no flowers.” Here, she articulates the essential role of winter rains in producing the natural beauty that follows, including every “bud or leaf.” The phrase “fattening rain” imbues the precipitation with a sense of richness and sustenance, as though the rain itself provides nourishment. Rossetti underscores that without this soaking, winter moisture, the world would be void of beauty and life, casting rain as a silent yet crucial player in nature’s abundance. This stanza reinforces the poem’s central theme: that rain, often associated with bleakness or inconvenience, is actually indispensable to nature’s beauty.

Stanza Five: The Web of Life

Continuing her exploration of rain’s role, Rossetti writes, “Never a mated bird / In the rocking tree-tops, / Never indeed a flock or herd / To graze upon the lea-crops.” This stanza highlights how deeply rain is woven into the fabric of life. Without it, birds and animals would have no sustenance; there would be no fields for flocks or herds to graze upon. Rossetti’s use of “mated bird” and the image of “rocking tree-tops” adds a rhythmic liveliness, capturing how rain’s effects ripple out to support various species. Her depiction of rain as integral to the ecological web underscores her reverence for the natural world and its systems of dependency.

Stanza Six: Nourishment and Abundance

The sixth stanza introduces sheep and lambs grazing on “sun-bright leas,” which would be barren were it not for “rain in season.” This stanza captures the full circle of nourishment in nature, with winter rains feeding the grass that will in turn feed the flocks. The image of “lambs so woolly white” and “sun-bright leas” suggests innocence and purity, creating a pastoral idyll that celebrates nature’s beauty and bounty. Through this imagery, Rossetti paints a vision of prosperity brought forth by the rain, connecting life’s simplicity and beauty to the reliability of nature’s cycles.

Stanza Seven: The Loss Without Rain

Rossetti turns to an image of absence in the seventh stanza, contemplating a world without rain: “We should find no moss / In the shadiest places, / Find no waving meadow-grass / Pied with broad-eyed daisies.” Here, she imagines an arid landscape, devoid of even moss or meadow-grass. This absence contrasts with the lush, vibrant imagery seen throughout the poem, driving home the significance of rain as a life-sustaining force. Moss, often found in dark, moist areas, symbolizes the presence of life even in hidden or overlooked places, underscoring rain’s role in supporting life both visible and hidden.

Final Stanza: The Stark Reality of Barrenness

The poem concludes with a striking vision of “miles of barren sand, / With never a son or daughter.” Here, Rossetti imagines a land without descendants—without growth or future. This image conveys a sense of desolation and sterility, a reminder that life and continuity depend on rain. She underscores this barrenness with the phrase “not a lily on the land, / Or lily on the water,” evoking an utter absence of beauty and fertility. The lily, often a symbol of purity and renewal, becomes an emblem of life’s fragility and the necessity of water for its survival. By ending on this image, Rossetti leaves readers with an impression of rain’s critical, almost sacred role in sustaining life.

Conclusion

In "Winter Rain," Christina Rossetti weaves a delicate yet profound meditation on the significance of rain as a source of life and renewal. Through rich imagery, she traces rain’s unseen yet crucial role in the natural cycles that bring forth spring’s beauty. Each stanza reveals a different aspect of rain’s gifts—from nurturing flowers to feeding flocks to supporting birds and insects—emphasizing rain as the unseen, essential force behind nature’s vibrancy. Rossetti’s poem ultimately calls for a deeper appreciation of rain, transforming what might initially seem bleak or mundane into a symbol of life’s interconnectedness and resilience.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!