What's in a Name?

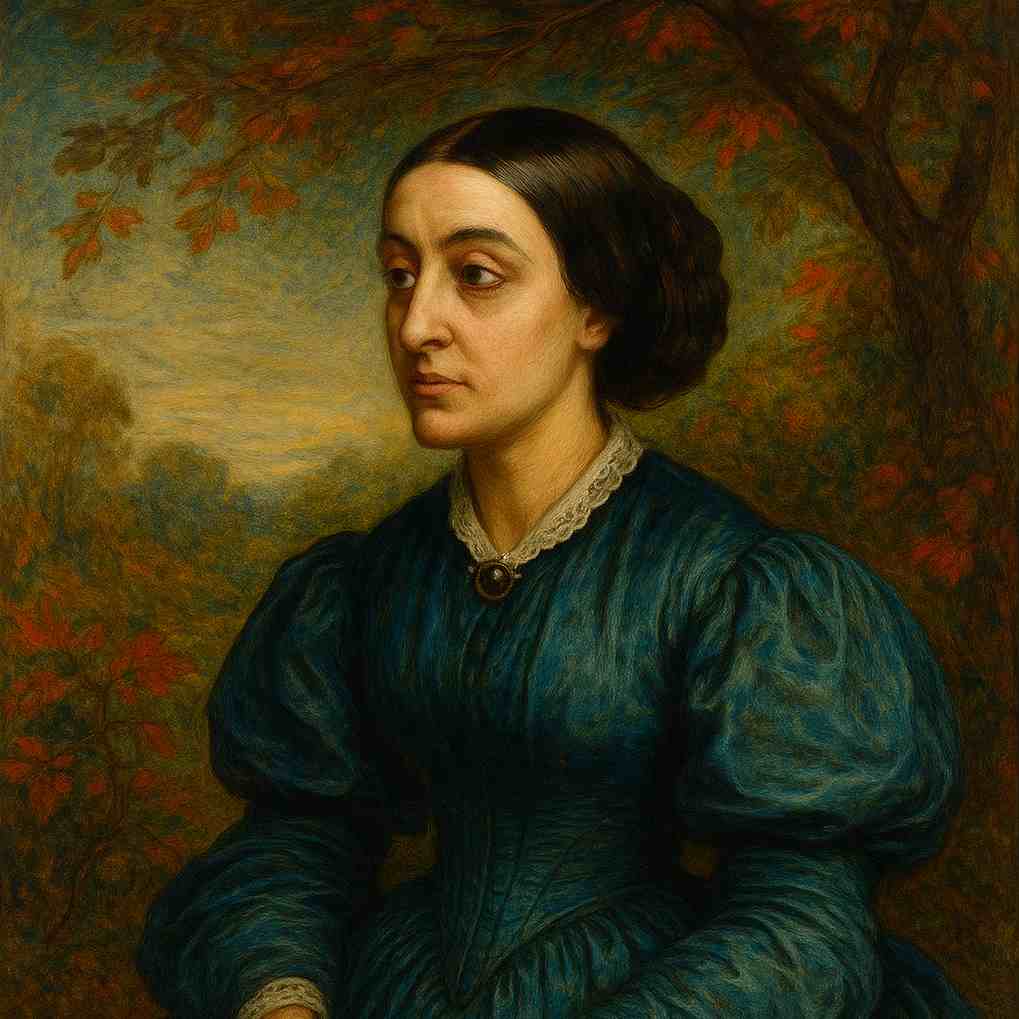

Christina Rossetti

1830 to 1894

Why has Spring one syllable less

Than any its fellow season?

There may be some other reason,

And I'm merely making a guess;

But surely it hoards such wealth

Of happiness, hope and health,

Sunshine and musical sound,

It may spare a foot from its name

Yet all the same

Superabound.

Soft-named Summer,

Most welcome comer,

Brings almost everything

Over which we dream or sing

Or sigh;

But then Summer wends its way,

To-morrow,--to-day,--

Good-bye!

Autumn,--the slow name lingers,

While we likewise flag;

It silences many singers;

Its slow days drag,

Yet hasten at speed

To leave us in chilly need

For Winter to strip indeed.

In all-lack Winter,

Dull of sense and of sound,

We huddle and shiver

Beside our splinter

Of crackling pine,

Snow in sky and snow on ground.

Winter and cold

Can't last for ever!

To-day, to-morrow, the sun will shine;

When we are old,

But some still are young,

Singing the song

Which others have sung,

Ringing the bells

Which others have rung,--

Even so!

We ourselves, who else?

We ourselves long

Long ago.

Christina Rossetti's What's in a Name?

Christina Rossetti’s poem “What’s in a Name?” explores the symbolic and emotional qualities of each season, engaging with the passage of time and the cyclical nature of life. Through succinct and lyrical language, Rossetti imbues each season with a distinct personality and rhythm, suggesting that the seasons are not merely time markers, but metaphors for stages of human life and emotion.

Structure and Form

The poem is organized into four stanzas, each dedicated to a single season. Rossetti’s choice of stanzaic organization and irregular rhyme scheme mirrors the variability and uniqueness of each season. The lines are metered unevenly, contributing to the distinctive rhythm and pacing that differentiates each stanza's tone. This approach enhances the sense of contrast among the seasons and aligns the reader’s experience with the fluctuating moods associated with each.

Analysis of Each Season

Spring

The poem opens with a question: “Why has Spring one syllable less / Than any its fellow season?” Rossetti speculates that Spring, though shorter in name, “hoards such wealth / Of happiness, hope and health,” that it does not need a longer syllabic presence. The meter is light and brisk, reflective of Spring's energy and new beginnings. The stanza is compact, reflecting the brevity but intensity of Spring, a season that “Superabound[s]” with vitality. Spring becomes a symbol of youthful optimism and potential, a time when life feels abundant and full.

Summer

The tone shifts in the second stanza, dedicated to “Soft-named Summer.” Here, Rossetti crafts an image of Summer as “Most welcome comer,” implying a period of joy and warmth. The season “Brings almost everything / Over which we dream or sing / Or sigh,” indicating the fullness of life and contentment that Summer embodies. However, there is a sense of fleetingness; Summer “wends its way” with a melancholic inevitability, and Rossetti reminds the reader that “To-morrow,—to-day,— / Good-bye!” Summer’s beauty is tinged with the sorrow of its ephemerality, mirroring the fleeting joys of youth and love.

Autumn

Autumn’s stanza is marked by a slower, heavier rhythm, capturing the sense of deceleration as the year progresses. Rossetti describes it as “the slow name” that “lingers,” symbolizing the gradual fading of energy and warmth. The lines “It silences many singers; / Its slow days drag” suggest a dimming vitality, and a movement toward stillness. The stanza conveys the solemnity of decline, as “we likewise flag.” This slowing down leads to an inevitable chill, the “chilly need” for Winter’s bareness. Autumn here reflects the stage in life of decline, where vibrancy fades, yet there is an acknowledgment of the beauty in slowing down and letting go.

Winter

Winter represents the end, or a kind of existential barrenness. It is described as “In all-lack Winter,” a time “Dull of sense and of sound.” Rossetti evokes a stark image of people “huddle[d] and shiver[ing] / Beside our splinter / Of crackling pine.” Winter becomes an emblem of loss and isolation, where life is reduced to survival in the cold and “snow on ground.” However, Rossetti does not let the poem remain in bleakness; instead, she offers a glimmer of hope with the acknowledgment that “Winter and cold / Can’t last for ever!” This mention of future warmth implies a cycle, suggesting that life will renew.

Theme of Cyclicality and Legacy

Rossetti meditates on the idea that as time progresses, what once was will return in a new form. In the concluding lines, she contemplates the human need to repeat and preserve traditions, “Singing the song / Which others have sung, / Ringing the bells / Which others have rung.” The repetition of actions performed by past generations underlines a connection between past and present, a continuity that transcends time. Winter, then, becomes a metaphor not just for death but for a period in which memories and traditions are cherished and revisited, reminding us that life and warmth will inevitably follow.

The closing lines—“Even so! / We ourselves, who else? / We ourselves long / Long ago”—suggest a return to past joys and a deep sense of continuity. Rossetti implies that though time passes and seasons change, the core of human experience remains unchanged. Our lives are intertwined with those who came before, bound by recurring emotions and universal rituals that make us part of an enduring cycle.

Conclusion

In “What’s in a Name?” Christina Rossetti skillfully personifies the seasons to explore the themes of change, continuity, and mortality. By evoking each season’s distinct characteristics, she captures the cyclical nature of life and the inevitability of both joy and sorrow. The poem serves as a meditation on the passage of time, suggesting that while each season brings its unique experiences, they collectively form a perpetual loop of beginnings and endings. Through this lens, Rossetti presents a gentle reassurance: life, in its various stages, remains connected, and even in the depths of Winter, there lies the promise of Spring’s renewal.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!