Brahma

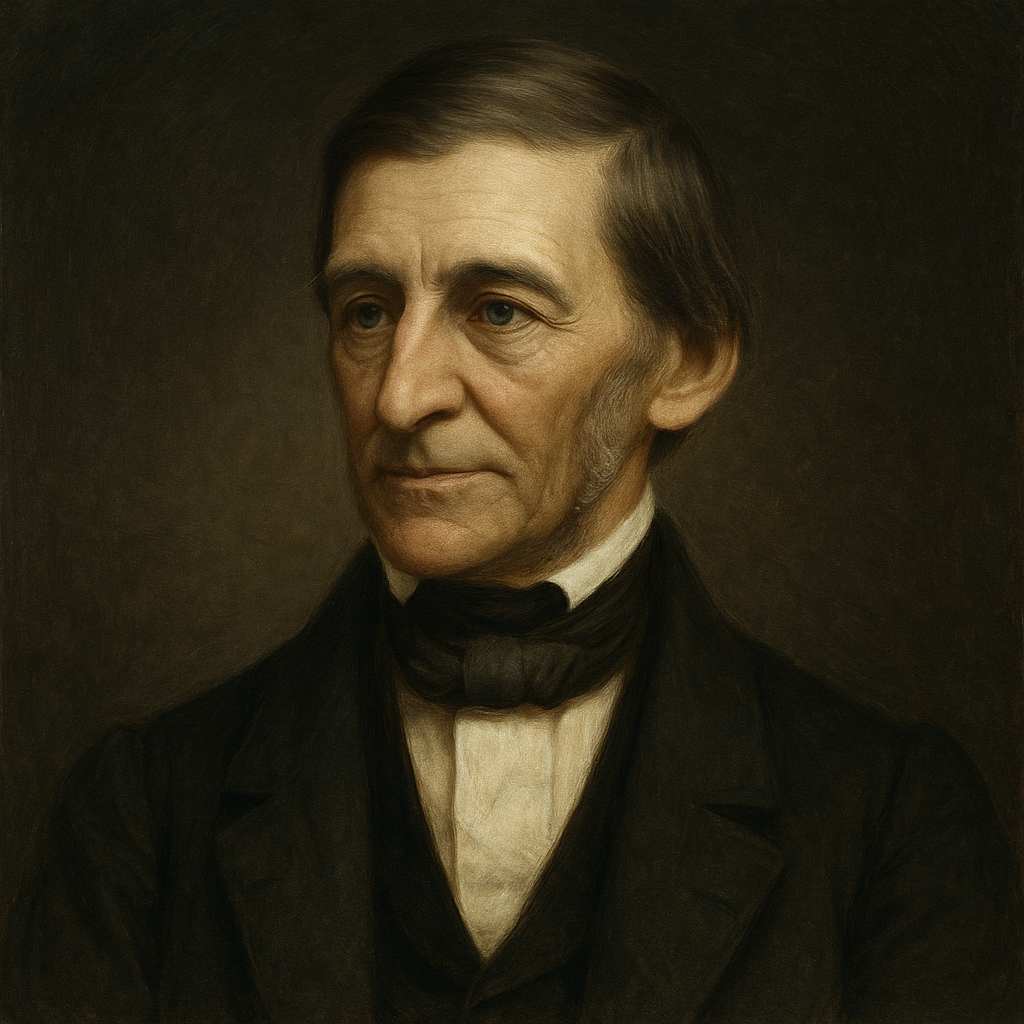

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803 to 1882

If the red slayer think he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain,

They know not well the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again.

Far or forgot to me is near;

Shadow and sunlight are the same;

The vanished gods to me appear;

And one to me are shame and fame.

They reckon ill who leave me out;

When me they fly, I am the wings;

I am the doubter and the doubt,

And I the hymn the Brahmin sings.

The strong gods pine for my abode,

And pine in vain the sacred Seven;

But thou, meek lover of the good!

Find me, and turn thy back on heaven.

Ralph Waldo Emerson's Brahma

Ralph Waldo Emerson's poem “Brahma,” first published in 1857, draws deeply on Hindu philosophy, particularly concepts from the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, to express a transcendent worldview. Written as if from the voice of Brahma, the Hindu god of creation and a representation of the ultimate, universal spirit, the poem explores the illusory nature of dualities, the omnipresence of the divine, and the path to spiritual enlightenment. In this analysis, I will examine how Emerson uses language, form, and themes to communicate a vision of unity and the transcendence of conventional human distinctions.

"Brahma" is one of Emerson’s attempts to convey the essence of Hindu mysticism to a Western audience, which would have been largely unfamiliar with such ideas in the mid-19th century. Emerson’s engagement with Transcendentalism—a movement he helped pioneer—brought him close to Eastern philosophies, particularly those that address the unity of existence. In this poem, Brahma, or the universal spirit, speaks directly to reveal the illusory nature of life and death, fame and shame, and all the dualistic thinking that confines human understanding.

Stanza 1: Illusion of Life and Death

If the red slayer think he slays,

Or if the slain think he is slain,

They know not well the subtle ways

I keep, and pass, and turn again.

The poem begins with an assertion of the illusion inherent in the concepts of life and death. Emerson introduces the idea of "the red slayer," a symbol for any killer or destroyer, whether human or cosmic, who believes in the reality of his action. However, Brahma, speaking as the eternal essence, reveals that both the act of killing and the experience of being killed are misunderstandings. The concepts of slayer and slain are fundamentally flawed because the true self, which is Brahma, cannot be destroyed. By stating "I keep, and pass, and turn again," Brahma expresses his eternal, cyclical nature—emphasizing reincarnation or the cyclical persistence of energy, which never truly ends but transforms endlessly.

Stanza 2: Unity of Opposites

Far or forgot to me is near;

Shadow and sunlight are the same;

The vanished gods to me appear;

And one to me are shame and fame.

In the second stanza, Emerson deepens his exploration of duality, or rather, the absence of it in Brahma’s reality. Words like "far" and "near," "shadow" and "sunlight," as well as "shame" and "fame," typically suggest opposing concepts; however, to Brahma, they are indistinguishable. This dissolution of binary distinctions reflects Advaita Vedanta, a non-dualistic school of Hindu philosophy that views all of existence as one unified reality. By stating that "shadow and sunlight are the same," Emerson emphasizes the transcendence of temporal conditions. This view aligns with the Transcendentalist idea that opposites are mere illusions and that at a higher level of consciousness, all things are harmonized in a single universal spirit.

Stanza 3: The Inescapable Divine Presence

They reckon ill who leave me out;

When me they fly, I am the wings;

I am the doubter and the doubt,

And I the hymn the Brahmin sings.

Here, Brahma addresses those who might ignore or reject his presence, warning that all attempts to escape the divine are futile. Emerson writes, "When me they fly, I am the wings," suggesting that Brahma, as the essence of all things, is both the seeker and the sought, the subject and the object, and even the process of seeking itself. This line reflects the Transcendentalist belief that divinity is omnipresent, imbuing every act, thought, and entity with sacredness. In a striking paradox, Brahma identifies himself as "the doubter and the doubt," implying that every skeptic’s question, every doubt, and even every answer all arise within Brahma’s own being. This reflects Emerson’s view that every aspect of human experience—even doubt and uncertainty—is a part of the divine journey.

Stanza 4: Transcendence Beyond Conventional Divinity

The strong gods pine for my abode,

And pine in vain the sacred Seven;

But thou, meek lover of the good!

Find me, and turn thy back on heaven.

In the final stanza, Brahma states that even the "strong gods" and the "sacred Seven" long to reside in his presence but are unable to attain it. The “sacred Seven” likely refers to the Saptarishi, the seven great sages of Hindu mythology who are connected with cosmic order and wisdom. The fact that these powerful beings "pine in vain" suggests that even they do not fully grasp Brahma’s essence. Emerson’s message here is that those who chase conventional religious aspirations or worship external gods may miss the true nature of Brahma. Only the "meek lover of the good"—a humble, devoted seeker of truth and goodness—can find Brahma by renouncing the material and even spiritual rewards promised by traditional notions of heaven. This renunciation of heaven is a metaphor for transcending dualistic thinking and understanding that ultimate truth lies within the self and beyond even the highest spiritual achievements.

Conclusion

Emerson’s “Brahma” invites readers to confront and question dualistic conceptions of reality—life and death, light and darkness, success and failure—and to recognize them as illusions that obscure the underlying unity of existence. Brahma’s voice in the poem functions as both a guide and a paradoxical challenge, urging the reader toward a higher form of understanding that defies logical binaries and conventional religious practices. Emerson’s poem illustrates the profound influence of Hindu philosophy on his work and demonstrates his belief in the unity of all existence, a hallmark of Transcendentalist thought. Through “Brahma,” Emerson encourages a spiritual perspective that is not reliant on external validation but rather seeks the divine within, in the quiet dissolution of distinctions and the embracing of an eternal, universal self.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!