A Dalesman's Litany

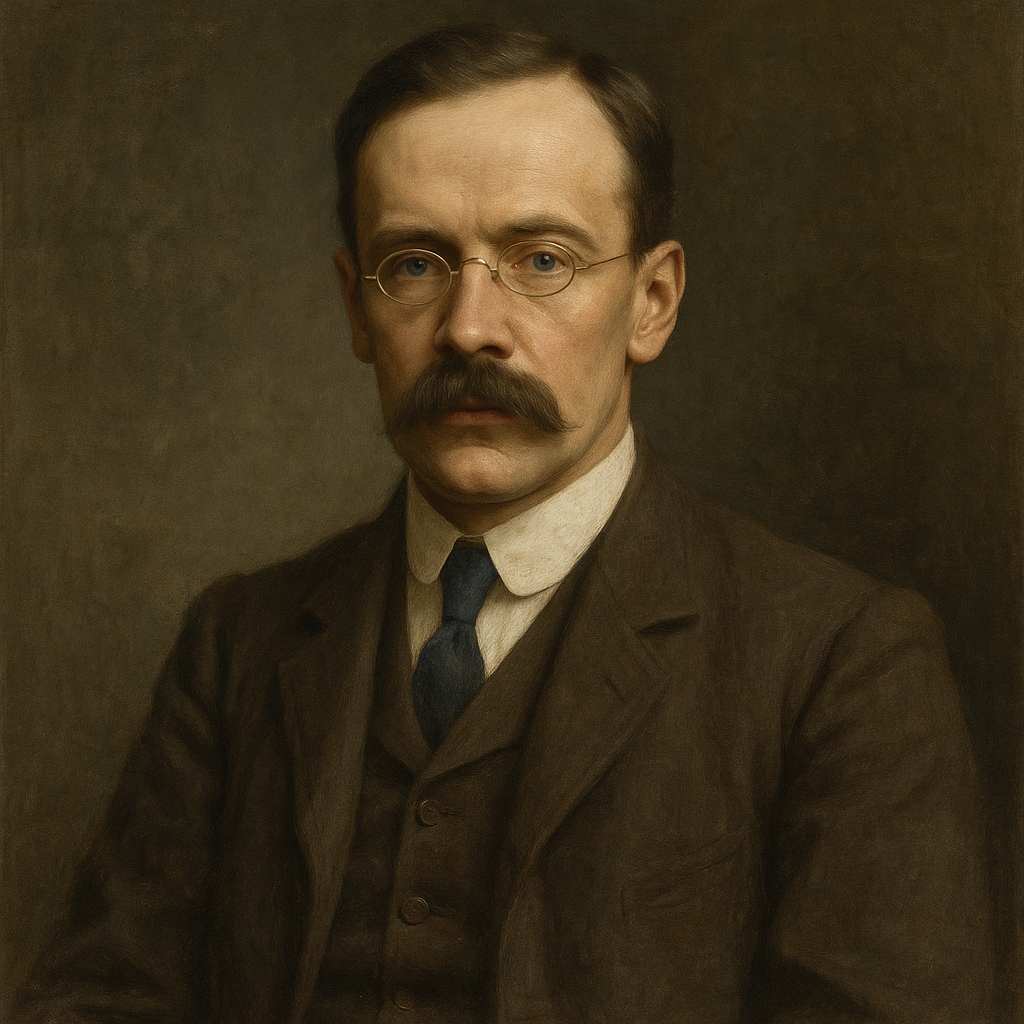

Frederic William Moorman

1872 to 1919

It's hard when fowks can't finnd their wark

Wheer they've bin bred an' born;

When I were young I awlus thowt

I'd bide 'mong t' roots an' corn.

But I've bin forced to work i' towns,

So here's my litany:

Frae Hull, an' Halifax, an' Hell,

Gooid Lord, deliver me!

When I were courtin' Mary Ann,

T' owd squire, he says one day:

"I've got no bield for wedded fowks;

Choose, wilt ta wed or stay? "

I couldn't gie up t' lass I loved,

To t' town we had to flee:

Frae Hull, an' Halifax, an' Hell,

Gooid Lord, deliver me!

I've wrowt i' Leeds an' Huthersfel',

An' addled honest brass;

I' Bradforth, Keighley, Rotherham,

I've kept my barns an' lass.

I've travelled all three Ridin's round,

And once I went to sea:

Frae forges, mills, an' coalin' boats,

Gooid Lord, deliver me!

I've walked at neet through Sheffield loans,

'T were same as bein' i' Hell:

Furnaces thrast out tongues o' fire,

An' roared like t' wind on t' fell.

I've sammed up coals i' Barnsley pits,

Wi' muck up to my knee:

Frae Sheffield, Barnsley, Rotherham,

Gooid Lord, deliver me!

I've seen grey fog creep ower Leeds Brig

As thick as bastile soup;

I've lived wheer fowks were stowed away

Like rabbits in a coop.

I've watched snow float down Bradforth Beck

As black as ebiny:

Frae Hunslet, Holbeck, Wibsey Slack,

Gooid Lord, deliver me!

But now, when all wer childer's fligged,

To t' coontry we've coom back.

There's fotty mile o' heathery moor

Twix' us an' t' coal-pit slack.

And when I sit ower t' fire at neet,

I laugh an' shout wi' glee:

Frae Bradforth, Leeds, an Huthersfel',

Frae Hull, an' Halifax, an' Hell,

T' gooid Lord's delivered me!

Frederic William Moorman's A Dalesman's Litany

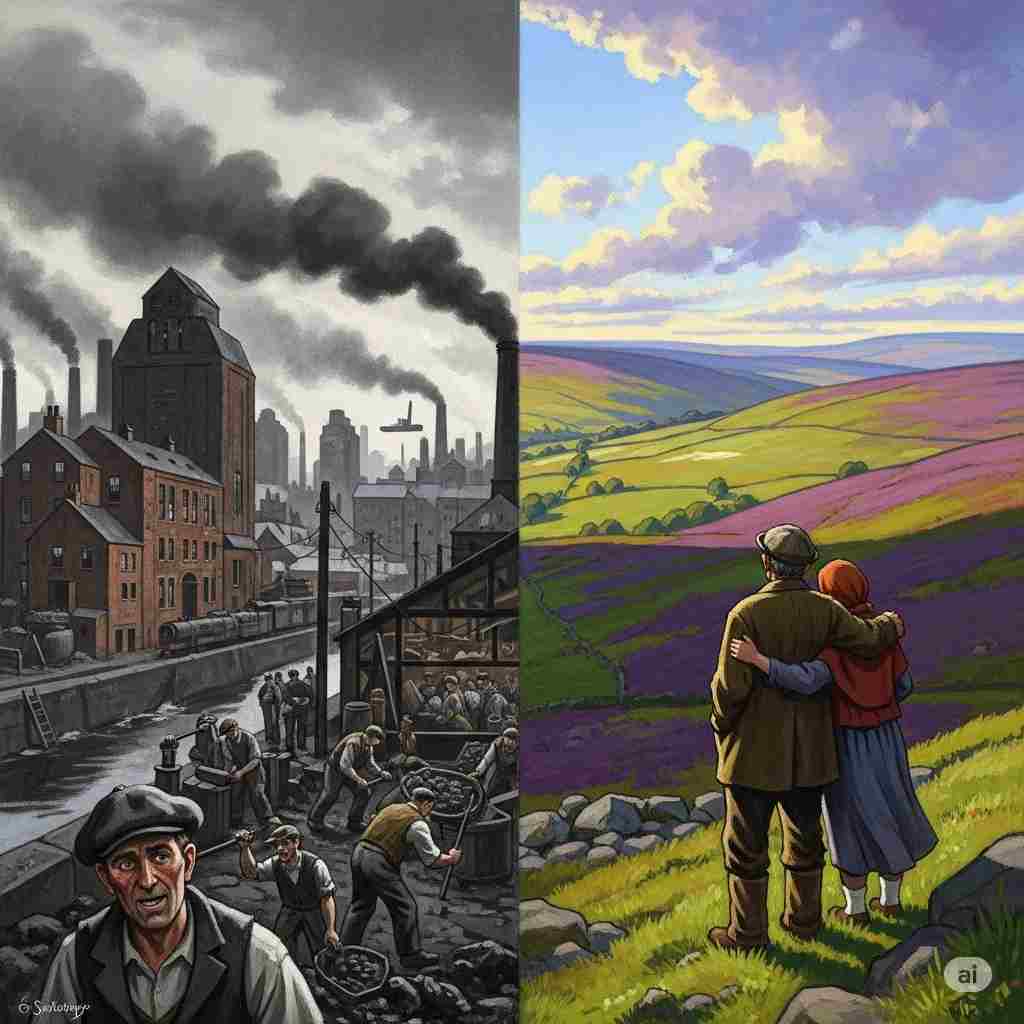

Frederic William Moorman’s A Dalesman’s Litany is a poignant expression of rural displacement, the brutality of industrial labor, and the yearning for home. Written in Yorkshire dialect, the poem captures the voice of a displaced rural laborer forced into urban and industrial work, lamenting his exile while ultimately finding solace in return. Through its vivid imagery, emotional depth, and cultural specificity, the poem serves as both a personal lament and a broader commentary on the upheavals of the Industrial Revolution. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its literary devices, central themes, and emotional resonance, while also considering philosophical and comparative perspectives.

Historical and Cultural Context: The Industrial Revolution’s Human Cost

To fully appreciate A Dalesman’s Litany, one must understand the seismic shifts brought about by the Industrial Revolution in 19th-century England. The poem reflects the mass displacement of rural workers who, due to enclosures, mechanized farming, and economic necessity, were forced into burgeoning industrial cities like Leeds, Sheffield, and Halifax. These urban centers, while offering employment, were often sites of exploitation, squalor, and dehumanizing labor conditions.

The speaker’s litany—"Frae Hull, an' Halifax, an' Hell, / Gooid Lord, deliver me!"—encapsulates the despair of rural migrants thrust into an alien world. The invocation of "Hell" alongside industrial towns is not mere hyperbole; for many, factory work, coal mining, and urban overcrowding were infernal experiences. The poem’s dialect roots it firmly in Yorkshire, a region deeply affected by industrialization, where the contrast between pastoral life and industrial blight was stark.

Moorman, a scholar of Yorkshire folklore and dialect, wrote with an acute awareness of these tensions. His work often celebrated rural traditions, making this poem a mournful counterpoint—an acknowledgment of the losses incurred by progress. The speaker’s journey from the countryside to the "forges, mills, an' coalin' boats" mirrors the historical trajectory of countless laborers whose lives were irrevocably altered by economic forces beyond their control.

Literary Devices: Dialect, Imagery, and Repetition

Moorman’s use of Yorkshire dialect is not merely ornamental; it is essential to the poem’s authenticity and emotional power. The vernacular grounds the poem in a specific cultural milieu, reinforcing the speaker’s identity as a displaced rural worker. Phrases like "addled honest brass" (earned honest money) and "fowks were stowed away / Like rabbits in a coop" convey both the speaker’s voice and the dehumanizing conditions of urban life.

The poem’s imagery is visceral and often apocalyptic. Industrial landscapes are rendered as realms of suffering: Sheffield’s furnaces "thrast out tongues o' fire," while Leeds is shrouded in a "grey fog... As thick as bastile soup." The reference to the workhouse ("bastile") is particularly telling, as workhouses were symbols of destitution and institutional cruelty. The speaker’s description of snow in Bradford Beck "As black as ebiny" (ebony) underscores the pollution and degradation of natural elements in industrial zones.

Repetition serves as both a structural and rhetorical device. The recurring plea—"Gooid Lord, deliver me!"—functions like a refrain in a folk ballad, reinforcing the speaker’s desperation. The litany of place names (Hull, Halifax, Hell; Sheffield, Barnsley, Rotherham) accumulates weight with each repetition, emphasizing the breadth of the speaker’s exile. Only in the final stanza, when the speaker returns to the countryside, does the refrain shift to triumphant relief: "T' gooid Lord's delivered me!"

Themes: Displacement, Labor, and Redemption

1. Displacement and Nostalgia

The central tension of the poem is between the rural idyll and the industrial nightmare. The speaker’s lament—"It's hard when fowks can't finnd their wark / Wheer they've bin bred an' born"—speaks to a profound rupture in identity. His forced migration ("To t' town we had to flee") is not just economic but existential; he is severed from the land that shaped him.

This theme resonates with broader literary traditions of pastoral elegy, where rural life is idealized in contrast to urban corruption. Yet Moorman avoids mere sentimentality; the speaker’s nostalgia is tempered by the recognition that return is only possible after enduring decades of toil.

2. The Brutality of Industrial Labor

The poem’s middle stanzas are a catalog of industrial suffering. The speaker has "sammed up coals i' Barnsley pits, / Wi' muck up to my knee," and walked Sheffield’s streets "same as bein' i' Hell." The comparison of industrial cities to hell is not accidental; it aligns with 19th-century critiques of industrialization by writers like Blake ("dark Satanic mills") and Dickens (Hard Times).

The labor described is not just physically grueling but spiritually corrosive. The speaker’s movement through multiple towns—Leeds, Huddersfield, Bradford—suggests a rootless existence, where work is transient and dignity scarce. The image of people "stowed away / Like rabbits in a coop" evokes the overcrowded slums of industrial cities, where workers were reduced to mere cogs in the machinery of capitalism.

3. Redemption and Return

The final stanza offers a rare moment of joy: the speaker, now aged, has returned to the countryside. The "heathery moor" symbolizes both natural beauty and freedom, standing in stark contrast to the "coal-pit slack" of industrial life. His triumphant cry—"T' gooid Lord's delivered me!"—suggests a hard-won salvation.

This redemption, however, is bittersweet. It comes only after a lifetime of suffering, and only because his children have "fligged" (grown and left). The poem thus acknowledges that while return is possible, it cannot undo the years of hardship.

Comparative and Philosophical Perspectives

A Dalesman’s Litany can be fruitfully compared to other works of industrial and rural literature. Thomas Hardy’s The Ruined Maid and John Clare’s The Moors similarly explore displacement, though from different angles. Clare’s poetry, in particular, laments the loss of the agrarian landscape, much like Moorman’s speaker mourns his forced exile.

Philosophically, the poem engages with Marx’s concept of alienation—the idea that industrial labor estranges workers from their humanity. The speaker’s litany is not just a prayer for physical deliverance but a cry against the spiritual desolation of mechanized work.

Emotional Impact: A Voice of the Dispossessed

What makes A Dalesman’s Litany so enduring is its raw emotional honesty. The speaker’s voice—weary, resilient, and ultimately triumphant—resonates with anyone who has experienced displacement. The poem’s power lies in its specificity; the Yorkshire dialect, the named towns, the visceral imagery all ground the suffering in reality.

Yet, the poem is not without hope. The final stanza’s joy is infectious, a testament to human endurance. The speaker’s laughter as he sits "ower t' fire at neet" is a small but profound victory, a reclaiming of the home he was once forced to leave.

Conclusion: A Testament to Resilience

Frederic William Moorman’s A Dalesman’s Litany is more than a regional poem; it is a universal lament for the displaced, a protest against dehumanizing labor, and a celebration of homecoming. Through its rich dialect, stark imagery, and emotional depth, the poem captures the human cost of industrialization while affirming the resilience of those who endure.

In an age of renewed discussions about labor, migration, and belonging, the poem’s themes remain startlingly relevant. It reminds us that while progress may be inevitable, its human toll must never be forgotten—and that redemption, however delayed, is always worth seeking.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!