The Parting Song

Felicia Dorothea Hemans

1793 to 1835

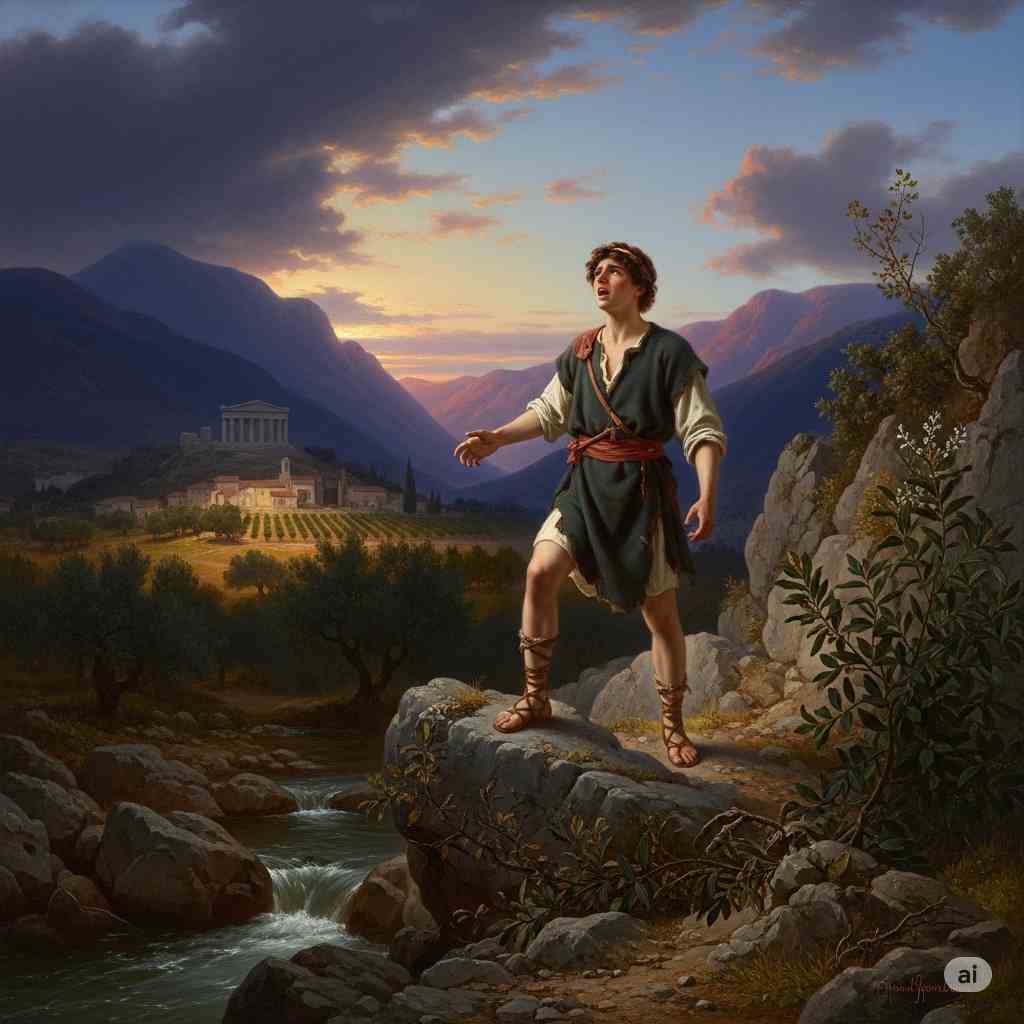

A youth went forth to exile, from a home

Such as to early thought gives images,

The longest treasur'd, and most oft recall'd,

And brightest kept, of love;—a mountain home,

That, with the murmur of its rocking pines

And sounding waters, first in childhood's heart

Wakes the deep sense of nature unto joy,

And half unconscious prayer;—a Grecian home,

With the transparence of blue skies o'erhung,

And, through the dimness of its olive shades,

Catching the flash of fountains, and the gleam

Of shining pillars from the fanes of old.

And this was what he left!—Yet many leave

Far more:—the glistening eye, that first from theirs

Call'd out the soul's bright smile; the gentle hand,

Which through the sunshine led forth infant steps

To where the violets lay; the tender voice

That earliest taught them what deep melody

Lives in affection's tones.—He left not these.

—Happy the weeper, that but weeps to part

With all a mother's love!—A bitterer grief

Was his—To part unlov'd! —of her unlov'd,

That should have breath'd upon his heart, like Spring,

Fostering its young faint flowers!

Yet had he friends,

And they went forth to cheer him on his way

Unto the parting spot—and she too went,

That mother, tearless for her youngest-born.

The parting spot was reach'd:—a lone deep glen,

Holy, perchance, of yore, for cave and fount

Were there, and sweet-voiced echoes; and above,

The silence of the blue, still, upper Heaven

Hung round the crags of Pindus, where they wore

Their crowning snows.—Upon a reck he sprung,

The unbelov'd one, for his home to gaze

Through the wild laurels back; but then a light

Broke on the stern proud sadness of his eye,

A sudden quivering light, and from his lips

A burst of passionate song.

"Farewell, farewell!

"I hear thee, O thou rushing stream!—thou 'rt from my native dell,

Thou 'rt bearing thence a mournful sound—a murmur of farewell!

And fare thee well—flow on, my stream!—flow on, thou bright and free!

I do but dream that in thy voice one tone laments for me;

But I have been a thing unlov'd, from childhood's loving years,

And therefore turns my soul to thee, for thou hast known my tears;

The mountains, and the caves, and thou, my secret tears have known:

The woods can tell where he hath wept, that ever wept alone!

"I see thee once again, my home! thou 'rt there amidst thy vines,

And clear upon thy gleaming roof the light of summer shines.

It is a joyous hour when eve comes whispering through thy groves,

The hour that brings the son from toil, the hour the mother loves!

—The hour the mother loves!—for me belov'd it hath not been;

Yet ever in its purple smile, thou smil'st, a blessed scene!

Whose quiet beauty o'er my soul through distant years will come—

—Yet what but as the dead, to thee, shall I be then, my home?

"Not as the dead!—no, not the dead!—We speak of them —we keep

Their names, like light that must not fade, within our bosoms deep!

We hallow ev'n the lyre they touch'd, we love the lay they sung,

We pass with softer step the place they fill'd our band among!

But I depart like sound, like dew, like aught that leaves on earth

No trace of sorrow or delight, no memory of its birth!

I go!—the echo of the rock a thousand songs may swell

When mine is a forgotten voice.—Woods, mountains, home, farewell!

"And farewell, mother!—I have borne in lonely silence long,

But now the current of my soul grows passionate and strong!

And I will speak! though but the wind that wanders through the sky,

And but the dark deep-rustling pines and rolling streams reply.

Yes! I will speak!—within my breast whate'er hath seem'd to be,

There lay a hidden fount of love, that would have gush'd for thee!

Brightly it would have gush'd, but thou, my mother! thou hast thrown

Back on the forests and the wilds what should have been thine own!

"Then fare thee well! I leave thee not in loneliness to pine,

Since thou hast sons of statelier mien and fairer brow than mine!

Forgive me that thou couldst not love!—it may be, that a tone

Yet from my burning heart may pierce, through thine, when I am gone!

And thou perchance mayst weep for him on whom thou ne'er hast smil'd,

And the grave give his birthright back to thy neglected child!

Might but my spirit then return, and 'midst its kindred dwell,

And quench its thirst with love's free tears!—'tis all a dream—farewell!"

"Farewell!"—the echo died with that deep word,

Yet died not so the late repentant pang

By the strain quicken'd in the mother's breast!

There had pass'd many changes o'er her brow,

And cheek, and eye; but into one bright flood

Of tears at last all melted; and she fell

On the glad bosom of her child, and cried

"Return, return, my son!"—the echo caught

A lovelier sound than song, and woke again,

Murmuring—"Return, my son!"—

Felicia Dorothea Hemans's The Parting Song

Felicia Dorothea Hemans's "The Parting Song" stands as one of the most emotionally powerful and technically accomplished poems of the Romantic era, yet it remains overshadowed by the works of her male contemporaries. This remarkable piece, with its profound exploration of maternal rejection, exile, and the ultimate triumph of love over indifference, deserves recognition as a masterwork of nineteenth-century poetry. Through its intricate narrative structure, vivid natural imagery, and deeply psychological portrayal of familial dysfunction, Hemans crafts a work that speaks to universal human experiences while remaining firmly rooted in the literary and cultural concerns of her time.

The poem's central narrative—a young man's exile from his Greek homeland and his final, desperate appeal to an unloving mother—operates on multiple levels of meaning. On its surface, it presents a straightforward tale of family conflict resolved through emotional catharsis. Yet beneath this narrative lies a complex meditation on belonging, identity, and the fundamental human need for love and acceptance. The work's emotional architecture moves from despair through defiance to reconciliation, creating a journey that mirrors the psychological processes of grief, anger, and healing.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate "The Parting Song," one must first understand the literary and cultural milieu from which it emerged. Felicia Dorothea Hemans (1793-1835) wrote during the height of the Romantic movement, a period characterized by intense interest in emotion, nature, and the sublime. The Romantic poets, including Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, and Shelley, had already established many of the conventions that Hemans would both embrace and subvert in her work. Her poetry emerged from a tradition that celebrated individual feeling and the power of personal experience, yet as a woman writer, she faced unique challenges in asserting her voice within this predominantly masculine literary landscape.

The early nineteenth century was a time of significant social and political upheaval. The Napoleonic Wars had reshaped European politics, and the struggle for Greek independence from Ottoman rule—beginning in earnest in the 1820s—captured the imagination of Romantic writers across Europe. Byron's death in Missolonghi in 1824 while supporting the Greek cause had made Greece a symbol of liberty and classical virtue fighting against tyranny. Hemans's choice to set her poem in a Greek landscape thus resonates with contemporary political sympathies while also invoking the classical tradition that was central to Romantic aesthetics.

The poem's Greek setting is not merely decorative but serves multiple symbolic functions. Greece represented the birthplace of Western civilization, democracy, and artistic achievement. For Romantic writers, it embodied the ideal of beauty and intellectual freedom that they sought to recapture in their own work. The "Grecian home" described in the opening lines, with its "transparence of blue skies," "olive shades," and "shining pillars from the fanes of old," establishes a connection between the protagonist's personal exile and the broader theme of separation from cultural and spiritual origins.

Furthermore, the Greek setting allows Hemans to explore themes of heritage and tradition that were particularly relevant to her historical moment. The early nineteenth century witnessed growing interest in national identity and cultural roots, partly in response to the social disruptions of industrialization and political revolution. The protagonist's separation from his Greek homeland thus becomes a metaphor for the broader sense of cultural displacement that many of Hemans's contemporaries experienced.

Literary Techniques and Narrative Structure

Hemans demonstrates remarkable technical skill in her handling of the poem's complex narrative structure. The work begins with third-person narration, establishing the scene and introducing the protagonist through external description. This objective perspective allows readers to observe the young man's situation with some emotional distance, preparing them for the intense subjectivity that will follow. The opening lines create a sense of loss and nostalgia through their catalog of what has been abandoned: the "mountain home," the "murmur of its rocking pines," and the "sounding waters" that first awakened the protagonist's connection to nature.

The transition to first-person narration marks a crucial shift in the poem's emotional register. When the protagonist "sprung" upon the rock and begins his "burst of passionate song," readers are suddenly thrust into his interior world. This technique allows Hemans to explore the psychology of rejection and exile with unprecedented intimacy. The young man's direct address to the landscape—"I hear thee, O thou rushing stream!"—creates a sense of immediacy and emotional urgency that would be impossible to achieve through continued third-person narration.

The poem's structure mirrors the psychological journey of its protagonist. The initial sections establish the context of exile and the pain of leaving home, while the central monologue explores the deeper emotional wounds of maternal rejection. The final section provides resolution through the mother's awakening to love, creating a satisfying narrative arc that moves from separation through confrontation to reconciliation. This structure reflects the influence of dramatic poetry, particularly the soliloquy tradition, while maintaining the lyrical intensity characteristic of Romantic verse.

Hemans's use of natural imagery serves multiple functions throughout the poem. The landscape is not merely a backdrop but an active participant in the emotional drama. The "rushing stream" becomes a confidant, the "mountains" and "caves" serve as witnesses to the protagonist's tears, and the "woods" preserve the memory of his solitary grief. This personification of nature reflects the Romantic belief in the spiritual connection between human consciousness and the natural world, while also providing the protagonist with sympathetic companions in his isolation.

The poem's dialogue between the protagonist and the landscape creates a sense of cosmic sympathy that contrasts sharply with the human indifference he has experienced. When he declares that "the mountains, and the caves, and thou, my secret tears have known," he establishes nature as a more reliable source of understanding than human relationships. This theme reflects the Romantic tendency to find spiritual solace in natural settings, but Hemans complicates this convention by ultimately affirming the importance of human love and connection.

Themes and Emotional Resonance

The central theme of "The Parting Song" is the devastating impact of maternal rejection on the human psyche. Hemans explores this theme with remarkable psychological sophistication, showing how the absence of parental love shapes every aspect of the protagonist's relationship with the world. The young man's description of himself as "a thing unlov'd, from childhood's loving years" reveals the deep wound at the center of his identity. This rejection has not merely caused him pain; it has fundamentally altered his sense of self-worth and belonging.

The poem's exploration of maternal rejection gains additional poignancy from its historical context. The early nineteenth century placed enormous emphasis on maternal love as a civilizing and nurturing force. The ideology of separate spheres assigned women the role of moral guardians of the home, making maternal affection a cornerstone of social stability. Hemans's portrayal of a mother who fails in this fundamental duty thus challenged contemporary assumptions about feminine nature and maternal instinct.

The protagonist's relationship with nature serves as a compensation for the human love he has been denied. His declaration that "therefore turns my soul to thee, for thou hast known my tears" establishes the natural world as a substitute mother, one who acknowledges and responds to his emotional needs. This theme reflects the Romantic belief in nature's spiritual power, but Hemans adds a psychological dimension that makes the relationship more complex and poignant. The protagonist's connection to nature is not simply aesthetic or philosophical; it is born from emotional necessity.

The poem also explores the theme of voice and silence, particularly in relation to power and recognition. The protagonist has "borne in lonely silence long," but his exile finally gives him the opportunity to speak his truth. His song becomes an act of self-assertion, a refusal to disappear without leaving a trace. The power of his voice ultimately transforms his situation, moving his mother from indifference to love. This theme resonates with Hemans's own position as a woman writer seeking recognition in a male-dominated literary world.

Memory and forgetting constitute another crucial theme in the poem. The protagonist fears that he will "depart like sound, like dew, like aught that leaves on earth / No trace of sorrow or delight, no memory of its birth." This anxiety about being forgotten reflects deeper concerns about identity and significance. The poem suggests that to be unloved is to risk complete erasure from human memory, a fate worse than death itself. The protagonist's song becomes an attempt to assert his existence and ensure his remembrance.

Comparative Analysis and Literary Influences

"The Parting Song" can be productively compared to other works of Romantic poetry, particularly those that explore themes of exile, nature, and family relationships. Byron's "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage" shares with Hemans's poem a focus on exile and the relationship between personal experience and landscape. However, while Byron's protagonist is a voluntary exile seeking adventure and experience, Hemans's protagonist is a victim of rejection forced into unwanted separation. This difference highlights Hemans's particular concern with the vulnerability of those who lack power and agency.

The poem also bears comparison to Wordsworth's explorations of memory and childhood experience. Like Wordsworth, Hemans recognizes the formative power of early experiences and the way they shape adult consciousness. However, where Wordsworth typically celebrates the positive influence of childhood memories, Hemans examines the lasting damage caused by childhood rejection. Her protagonist's relationship with nature, while healing, cannot fully compensate for the absence of human love.

Shelley's "Mont Blanc" provides another useful point of comparison, particularly in its use of natural imagery to explore philosophical and emotional themes. Both poems use the alpine landscape as a setting for profound contemplation, but Hemans's work is more explicitly concerned with personal relationships and domestic emotion. Where Shelley's poem moves toward abstract philosophical speculation, Hemans maintains focus on the particular human drama of her protagonist.

The influence of gothic literature can also be detected in "The Parting Song," particularly in its exploration of family dysfunction and psychological torment. The poem's emphasis on hidden emotion, long-suppressed truth, and dramatic revelation echoes gothic conventions, though Hemans ultimately rejects the gothic's tendency toward irresolution and despair. Her poem's happy ending, with the mother's awakening to love, provides the redemption that gothic literature typically denies.

Biographical Resonance and Personal Context

Understanding Hemans's personal circumstances adds another layer of meaning to "The Parting Song." Her own experience of family separation and emotional isolation informs the poem's psychological authenticity. Hemans was abandoned by her husband when she was twenty-five, leaving her to raise five children alone while supporting herself through her writing. This experience of abandonment and the struggle to maintain family connections despite geographical and emotional distance clearly influences the poem's exploration of separation and longing.

The poem's focus on maternal-child relationships may also reflect Hemans's own complex relationship with motherhood. As a working mother in an era when such roles were barely recognized, she faced the constant challenge of balancing her literary ambitions with her domestic responsibilities. The poem's portrayal of a mother who fails to provide adequate love may express some of Hemans's own anxieties about her ability to nurture her children while pursuing her career.

The theme of voice and recognition in the poem resonates with Hemans's position as a woman writer seeking acknowledgment in a male-dominated literary world. Like her protagonist, she needed to assert her voice and demand recognition for her emotional and artistic worth. The poem's ultimate affirmation of the power of passionate expression reflects her own belief in the importance of her literary voice.

Philosophical and Psychological Dimensions

"The Parting Song" engages with several philosophical questions that were central to Romantic thought. The poem explores the relationship between individual identity and social recognition, asking whether the self can exist meaningfully without acknowledgment from others. The protagonist's fear of being forgotten suggests that personal identity depends partly on social memory and recognition. This theme anticipates later philosophical explorations of the social construction of identity while remaining grounded in immediate emotional experience.

The poem also examines the nature of love and its relationship to human flourishing. The protagonist's description of the "hidden fount of love" that would have "gush'd" for his mother suggests that love is a natural human capacity that requires only the opportunity for expression. This psychological insight anticipates modern understanding of attachment theory and the importance of early emotional bonds for healthy development.

The work's exploration of the relationship between nature and human consciousness reflects Romantic philosophical concerns about the mind's relationship to the external world. The protagonist's ability to find sympathy in nature while being rejected by humans suggests that consciousness can form meaningful connections with the non-human world. This theme reflects the Romantic belief in nature's spiritual significance while also serving the poem's psychological purposes.

Emotional Impact and Universal Themes

The enduring power of "The Parting Song" lies in its ability to transform specific circumstances into universal experiences. While the poem's setting and characters are particular to early nineteenth-century Greece, its exploration of rejection, exile, and the longing for love speaks to fundamental human experiences that transcend historical and cultural boundaries. The protagonist's pain at being unloved and his desperate desire for recognition resonate with readers across different contexts and time periods.

The poem's emotional trajectory—from despair through defiance to reconciliation—mirrors psychological processes that remain relevant to contemporary readers. The protagonist's journey from silence to voice, from acceptance of rejection to demand for recognition, reflects the psychological work required to overcome trauma and assert one's worth. This emotional authenticity gives the poem its lasting power and relevance.

The work's exploration of family dysfunction and the possibility of healing also speaks to contemporary concerns. The poem's suggestion that even deeply damaged relationships can be transformed through honest communication and emotional courage provides hope for readers dealing with similar challenges. The mother's final awakening to love demonstrates the possibility of change and redemption, even in the most difficult circumstances.

Literary Legacy and Critical Reception

"The Parting Song" represents Hemans at her most accomplished, demonstrating her ability to combine technical skill with profound emotional insight. The poem's complex narrative structure, sophisticated use of natural imagery, and psychological depth place it among the finest achievements of Romantic poetry. Yet like much of Hemans's work, it has been overshadowed by the poetry of her male contemporaries, receiving insufficient critical attention and recognition.

Recent feminist scholarship has begun to reassess Hemans's contributions to Romantic poetry, recognizing her unique perspective on themes of home, family, and emotional life. "The Parting Song" exemplifies her ability to explore these themes with complexity and sophistication, offering insights that complement and sometimes challenge the work of her male contemporaries. The poem's focus on maternal-child relationships and domestic emotion provides a different perspective on Romantic concerns with individuality and social connection.

The poem's influence can be traced in later nineteenth-century poetry, particularly in works that explore family relationships and psychological trauma. Its technical innovations, including the integration of dramatic monologue with lyrical poetry, anticipate later developments in poetic form. The work's emphasis on the power of voice and expression also prefigures later concerns with identity and self-assertion.

Conclusion

"The Parting Song" stands as a masterpiece of Romantic poetry, demonstrating Felicia Dorothea Hemans's ability to combine technical excellence with profound emotional insight. Through its exploration of exile, rejection, and the ultimate triumph of love, the poem speaks to fundamental human experiences while remaining firmly rooted in the literary and cultural concerns of its historical moment. The work's complex narrative structure, sophisticated use of natural imagery, and psychological depth place it among the finest achievements of early nineteenth-century poetry.

The poem's enduring relevance lies in its authentic portrayal of emotional trauma and the possibility of healing. Hemans's protagonist, in his journey from silence to voice, from acceptance of rejection to demand for recognition, embodies the psychological work required to overcome difficult circumstances and assert one's worth. The mother's final awakening to love demonstrates the possibility of transformation and redemption, even in the most challenging family situations.

"The Parting Song" deserves recognition not merely as a historically significant work but as a poem that continues to speak to contemporary readers with emotional power and artistic excellence. Its exploration of themes such as belonging, identity, and the fundamental human need for love and acceptance remains as relevant today as it was when Hemans first penned these lines. The poem stands as a testament to the enduring power of poetry to transform personal experience into universal truth, to give voice to the voiceless, and to affirm the possibility of love and redemption in even the most difficult circumstances.

In the broader context of Romantic poetry, "The Parting Song" represents a unique contribution that enriches our understanding of the period's literary achievements. Hemans's focus on domestic emotion and family relationships provides a different perspective on Romantic themes of individuality and social connection, while her technical innovations anticipate later developments in poetic form. The poem's ultimate affirmation of the power of love and the possibility of change offers a hopeful vision that balances the Romantic tendency toward despair and alienation.

The work reminds us that the greatest poetry emerges not from abstract philosophical speculation but from the intersection of personal experience and universal truth. Hemans's ability to transform her own experiences of abandonment and struggle into a work of lasting artistic merit demonstrates the poet's essential function: to give shape and meaning to human experience, to find the universal in the particular, and to offer hope and understanding to those who share our common humanity. "The Parting Song" fulfills this function with remarkable success, earning its place among the enduring achievements of English literature.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!