Address to a Haggis

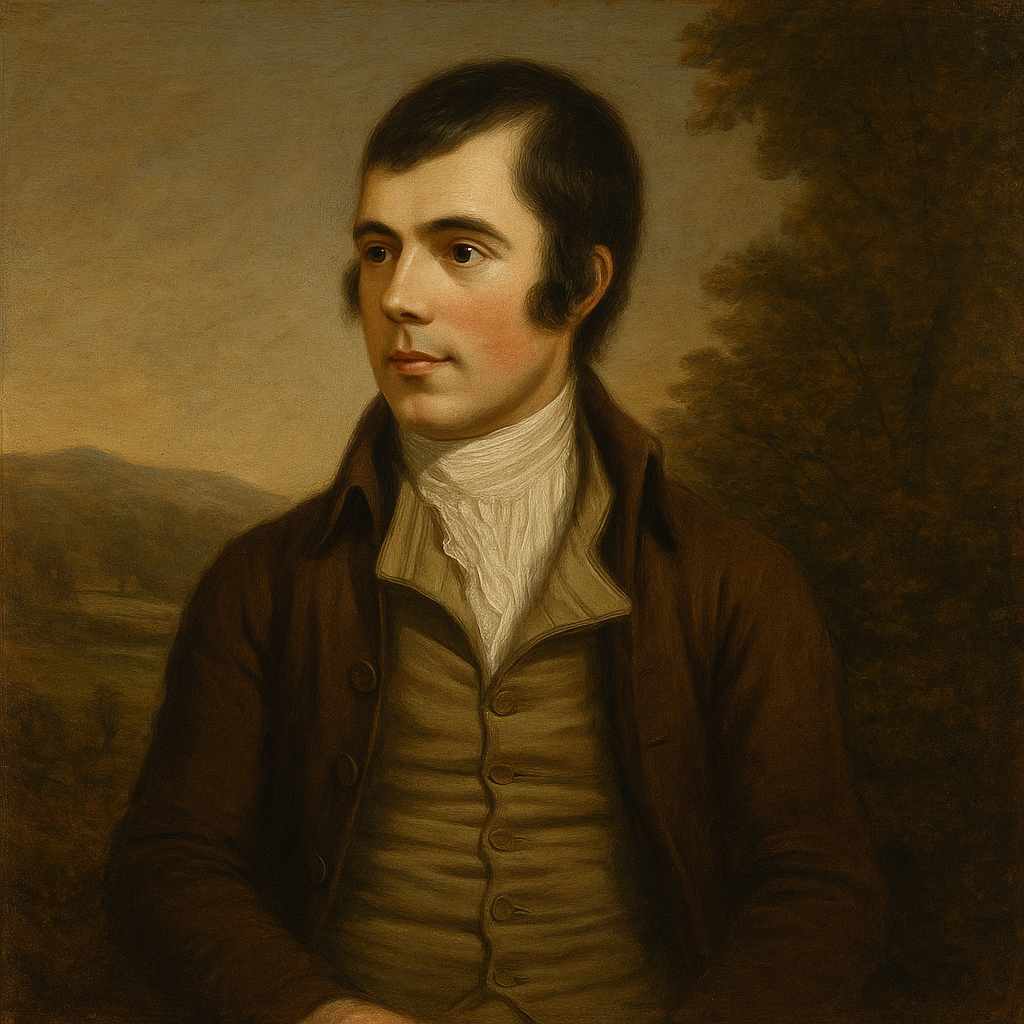

Robert Burns

1759 to 1796

Fair fa' your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o' the puddin'-race!

Aboon them a' ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o' a grace

As lang's my arm.

The groaning trencher there ye fill,

Your hurdies like a distant hill,

Your pin wad help to mend a mill

In time o' need,

While thro your pores the dews distil

Like amber bead.

His knife see rustic Labour dight,

An' cut you up wi' ready slight,

Trenching your gushing entrails bright,

Like onie ditch;

And then, O what a glorious sight,

Warm-reekin, rich!

Then, horn for horn, they stretch an' strive:

Deil tak the hindmost, on they drive,

Till a' their weel-swall'd kytes belyve

Are bent like drums;

The auld Guidman, maist like to rive,

'Bethankit' hums.

Is there that owre his French ragout,

Or olio that wad staw a sow,

Or fricassee wad mak her spew

Wi' perfect scunner,

Looks down wi' sneering, scornfu' view

On sic a dinner?

Poor devil! see him owre his trash,

As feckless as a wither'd rash,

His spindle shank a guid whip-lash,

His nieve a nit;

Thro' bloody flood or field to dash,

O how unfit!

But mark the Rustic, haggis-fed,

The trembling earth resounds his tread,

Clap in his walie nieve a blade,

He'll make it whissle;

An' legs an' arms, an' heads will sned,

Like taps o' thrissle.

Ye Pow'rs, wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o' fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware

That jaups in luggies:

But, if ye wish her gratefu' prayer,

Gie her a Haggis!

Robert Burns's Address to a Haggis

Robert Burns’ Address to a Haggis (1786) is more than a whimsical tribute to a traditional Scottish dish; it is a robust celebration of Scottish identity, cultural pride, and the virtues of rustic simplicity over foreign refinement. Written in Burns’ characteristic Scots dialect, the poem elevates the haggis—a humble peasant food—to the status of a national symbol, while simultaneously critiquing the pretensions of cosmopolitan tastes. This essay explores the poem’s historical and cultural context, its rich literary devices, its thematic concerns, and its emotional resonance, demonstrating how Burns crafts a work that is at once humorous, patriotic, and philosophically profound.

Historical and Cultural Context

To fully appreciate Address to a Haggis, one must understand the socio-political climate of late 18th-century Scotland. The Act of Union (1707) had dissolved Scotland’s independent parliament, integrating it into Great Britain. While this brought economic and political stability, it also led to cultural anxieties—Scottish traditions, language, and customs were increasingly overshadowed by English influence. The Scottish Enlightenment had fostered intellectual pride, but there was also a growing nostalgia for Scotland’s rural heritage, which Burns embodied in his poetry.

The haggis itself—a dish made from sheep’s offal, oats, and spices, encased in a stomach—was a staple of Scottish peasant life. By exalting it, Burns performs a cultural reclamation, asserting the dignity of Scottish traditions against the fashionable French cuisine favored by the elite. The poem was written during a period when Scottish national identity was being romanticized, partly in response to the suppression of Highland culture after the Jacobite rebellions. Burns’ choice to write in Scots dialect—a linguistic act of defiance—further reinforces this cultural assertion.

Literary Devices and Structure

Burns employs a variety of literary techniques to elevate the haggis into a heroic figure while satirizing those who disdain it. The poem’s tone is mock-epic, treating the haggis with the grandeur typically reserved for classical heroes or deities. The opening apostrophe—"Fair fa' your honest, sonsie face"—immediately anthropomorphizes the dish, bestowing it with a jovial, almost noble character. The exclamatory style mimics ceremonial oratory, reinforcing the poem’s performative aspect (it was likely recited at Burns Night suppers).

Imagery plays a crucial role in the poem’s visceral appeal. Burns describes the haggis in vivid, almost grotesque detail—"Your hurdies like a distant hill" and "Trenching your gushing entrails bright"—creating a tactile, sensory experience. The language is deliberately earthy, celebrating the dish’s physicality in contrast to the effete delicacies of French cuisine. Similes such as "Like amber bead" (referring to the fat glistening on the haggis) paradoxically blend rustic and luxurious imagery, reinforcing the poem’s central argument that Scottish fare is both hearty and exquisite.

Hyperbole is another key device. The haggis is not merely food but a "Great chieftain o' the puddin'-race!"—a hyperbolic honorific that humorously elevates it above all other dishes. The exaggerated physical reactions of those who eat it ("The trembling earth resounds his tread") suggest that consuming haggis bestows near-mythic strength, a satirical jab at the perceived effeteness of those who prefer French ragout.

The poem’s structure reinforces its thematic contrasts. The first three stanzas glorify the haggis, the next two mock those who scorn it, and the final stanza serves as a patriotic benediction. This tripartite structure mirrors a rhetorical argument: presentation of the subject, refutation of opposing views, and a concluding appeal to higher powers.

Themes and Philosophical Undercurrents

At its core, Address to a Haggis is a meditation on cultural authenticity versus artificial sophistication. Burns contrasts the haggis—a symbol of Scottish resilience and resourcefulness—with French delicacies, which he portrays as decadent and unmanly. The speaker derides the "Poor devil!" who consumes "French ragout" as feeble and unfit for battle ("His spindle shank a guid whip-lash"), whereas the haggis-eater is robust and formidable ("He'll make it whissle; / An legs an' arms, an' heads will sned"). This dichotomy reflects Enlightenment-era debates about natural virtue versus corrupt refinement, echoing Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s idealization of the "noble savage."

The poem also engages with class dynamics. The haggis, a working-class dish, is valorized over the aristocratic olio or fricassee. Burns, a tenant farmer himself, champions the dignity of rural labor, suggesting that true strength and virtue lie not in elite delicacies but in the honest sustenance of common folk. This aligns with his broader poetic project of giving voice to Scotland’s peasantry.

Nationalism is another prominent theme. The final stanza transforms the haggis into a metonym for Scotland itself. The invocation of "Ye Pow'rs" to grant Scotland "a Haggis" is both a prayer and a declaration of cultural self-sufficiency. Burns implies that Scotland does not need foreign imports ("nae skinking ware / That jaups in luggies")—it has its own rich traditions worthy of reverence.

Emotional Impact and Comparative Analysis

The poem’s emotional power lies in its exuberant celebration of the ordinary. Burns’ enthusiasm is infectious; his hyperbolic praise of the haggis invites readers to share in his delight. The humor—ranging from playful ("Weel are ye wordy o' a grace / As lang's my arm") to scathing ("Looks down wi' sneering, scornfu view")—creates a dynamic tonal range that keeps the poem engaging.

Comparatively, Address to a Haggis can be read alongside Burns’ other works, such as To a Mouse or Auld Lang Syne, which similarly blend humor, pathos, and national sentiment. It also resonates with other mock-heroic poems like Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock, though Burns’ work is more overtly political, using humor to assert cultural pride rather than merely satirize vanity.

Biographically, Burns’ own life as a farmer and exciseman informs the poem’s perspective. His deep connection to rural Scotland and his resentment of aristocratic pretension animate the text, giving it an authenticity that transcends mere parody.

Conclusion

Address to a Haggis is a masterful blend of humor, nationalism, and social commentary. Through its vivid imagery, hyperbolic praise, and biting satire, Burns elevates a simple dish into a symbol of Scottish identity while critiquing the hollow sophistication of foreign tastes. The poem’s enduring popularity—evidenced by its central role in Burns Night celebrations—testifies to its emotional resonance and cultural significance. More than just a whimsical ode, it is a defiant assertion of Scottish pride, a celebration of the common man, and a testament to the power of poetry to transform the mundane into the heroic. In Burns’ hands, the haggis becomes not just food, but a feast for the national soul.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!