The Wind and the Rain

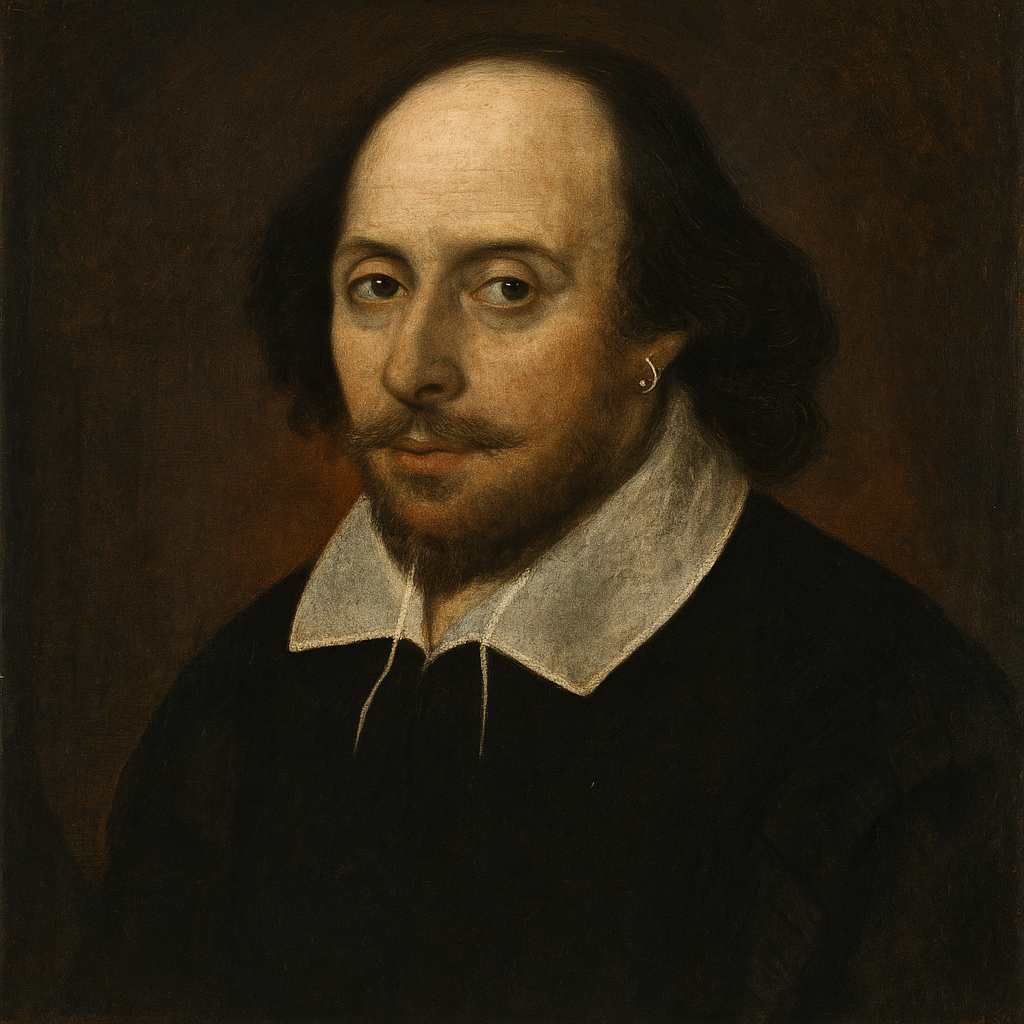

William Shakespeare

1564 to 1616

When that I was and a little tiny boy,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

A foolish thing was but a toy,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came to man’s estate,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

’Gainst knaves and thieves men shut their gate,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came, alas! to wive,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

By swaggering could I never thrive,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came unto my beds,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

With toss-pots still had drunken heads,

For the rain it raineth every day.

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

But that’s all one, our play is done,

And we’ll strive to please you every day.

William Shakespeare's The Wind and the Rain

William Shakespeare's "The Wind and the Rain" stands as one of the most haunting and philosophically complex songs in the dramatic canon, serving as the epilogue to Twelfth Night and offering a profound meditation on the human condition. This deceptively simple ballad, sung by the fool Feste at the play's conclusion, transforms what might appear to be a lighthearted ditty into a darkly compelling vision of life's inevitable disappointments and the persistence of natural forces beyond human control. Through its cyclical structure, vivid imagery, and haunting refrain, the poem explores themes of disillusionment, the passage of time, and the fundamental disconnect between human aspirations and natural reality.

Historical and Cultural Context

The poem emerges from the rich tradition of Elizabethan and Jacobean theater, where songs served not merely as entertainment but as philosophical commentary on the dramatic action. Written around 1601-1602, during the height of Shakespeare's creative powers, "The Wind and the Rain" reflects the cultural anxieties of a society grappling with religious upheaval, social transformation, and philosophical uncertainty. The late Renaissance period in England was marked by a growing awareness of human limitations and the capricious nature of fortune, themes that permeate much of Shakespeare's mature work.

The song's folk-ballad structure connects it to the oral tradition of popular culture, employing the repetitive, almost hypnotic quality characteristic of traditional songs passed down through generations. This form serves a dual purpose: it makes the philosophical content accessible to audiences across social strata while simultaneously lending the verses an air of ancient wisdom and inevitability. The choice to conclude Twelfth Night with such a song reflects Shakespeare's sophisticated understanding of how popular forms could carry profound metaphysical weight.

The cultural context of Elizabethan England, with its harsh social realities beneath the glittering court culture, provides essential background for understanding the poem's darker implications. The references to "knaves and thieves" and the necessity of shutting gates against them reflect the genuine social anxieties of a period marked by economic uncertainty and social mobility. The image of "toss-pots still had drunken heads" evokes the tavern culture that formed such an important part of early modern social life, while simultaneously suggesting the escapist tendencies that poverty and disappointment might engender.

Literary Devices and Structural Analysis

The poem's most striking feature is its relentless repetition, which serves multiple artistic functions. The refrain "With hey, ho, the wind and the rain" appears in every stanza, creating a sense of inexorable rhythm that mirrors the natural cycles it describes. This repetition functions as a kind of musical ostinato, establishing a hypnotic quality that draws listeners into the poem's philosophical meditation. The phrase "For the rain it raineth every day" serves as both conclusion and explanation, suggesting that the constants of existence—represented by rain—persist regardless of human circumstances or aspirations.

Shakespeare employs the device of parallelism to structure the poem's journey through life's stages. Each stanza begins with "But when I came," creating a sense of progression while simultaneously emphasizing the cyclical nature of experience. This parallel structure serves to highlight the similarities between different life stages rather than their differences, suggesting that human experience, despite its apparent variety, follows predictable patterns of disappointment and accommodation.

The poem's imagery operates on multiple levels, with the wind and rain serving as both literal weather phenomena and metaphorical representations of life's uncontrollable forces. The weather imagery evokes the pastoral tradition in English literature, but Shakespeare subverts the conventional associations of rain with renewal and growth. Instead, the rain becomes a symbol of persistence without purpose, continuity without meaning—a force that simply "raineth every day" regardless of human joy or sorrow.

The use of archaic language and syntax ("When that I was," "raineth") creates temporal distance that reinforces the poem's themes of memory and the passage of time. This linguistic choice also connects the song to the folk tradition, lending it an air of timeless wisdom while simultaneously emphasizing its role as a retrospective meditation on a completed life.

Thematic Exploration

The poem's central theme revolves around the tension between human aspiration and natural indifference. Each stanza presents a different life stage characterized by specific hopes and disappointments, yet all are unified by the unchanging presence of wind and rain. This juxtaposition suggests that while human experience varies dramatically across time and circumstance, the fundamental conditions of existence remain constant and largely indifferent to human concerns.

The theme of disillusionment emerges gradually through the poem's progression. The speaker's journey from childhood, where "a foolish thing was but a toy," through adulthood's recognition of social dangers, to marriage's failure to provide satisfaction, and finally to old age's retreat into drink, traces a trajectory of diminishing expectations. Each stage represents not growth or development but rather a progressive accommodation to disappointment. The poem suggests that maturity consists not in achieving one's goals but in learning to accept their impossibility.

Time functions as both structure and theme, with the poem's chronological organization emphasizing the linear progression of individual life while the cyclical refrains suggest the repetitive nature of existence. This temporal duality reflects one of Shakespeare's recurring preoccupations: the way individual lives follow linear trajectories toward death while the patterns of human experience repeat endlessly across generations. The final stanza's reference to "a great while ago the world begun" places the speaker's individual experience within cosmic time, suggesting both the insignificance of personal disappointment and the universality of human experience.

The theme of performance and artifice, introduced through the final lines about the "play" being "done," adds another layer of complexity. The poem's conclusion acknowledges its own fictional status while simultaneously asserting its truth value. This meta-theatrical element suggests that art's function is not to provide escape from life's difficulties but to help audiences understand and accept them. The promise to "strive to please you every day" parallels the rain's daily persistence, suggesting that both natural forces and human creativity continue regardless of their reception or effectiveness.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Implications

The poem's emotional power derives largely from its ability to transform melancholy into a kind of resigned wisdom. The speaker's tone throughout suggests neither bitter complaint nor cheerful acceptance but rather a weary acknowledgment of life's fundamental patterns. This emotional stance—neither optimistic nor pessimistic but simply observant—creates a complex affective response that resists easy categorization.

The repetitive structure contributes significantly to the poem's emotional impact by creating a sense of inexorable progression. The refrain's return in each stanza becomes increasingly weighted with accumulated disappointment, yet the rhythm remains steady and almost comforting. This tension between content and form mirrors the poem's thematic concerns: the way human beings find solace in pattern and repetition even when those patterns confirm life's disappointments.

The poem's philosophical implications extend beyond individual experience to encompass broader questions about the nature of existence and meaning. The constant rain suggests a universe governed by natural law rather than divine providence or human will. This naturalistic vision, while potentially disturbing, also offers a kind of comfort through its consistency. If life's difficulties are as natural and inevitable as weather, then perhaps individual failures need not be sources of personal shame or cosmic anxiety.

The final stanza's shift from personal narrative to universal statement—"A great while ago the world begun"—elevates the speaker's individual experience to the level of general truth. This movement from particular to universal suggests that personal disappointment, when properly understood, connects individuals to the broader human condition rather than isolating them within private suffering.

Comparative Analysis and Literary Tradition

"The Wind and the Rain" participates in several literary traditions while simultaneously subverting their conventional expectations. The poem's ballad form connects it to the folk tradition of narrative songs, but Shakespeare transforms the typical ballad's focus on dramatic events into a meditation on the absence of significant occurrence. Where traditional ballads celebrate heroic actions or tragic loves, this poem finds meaning in the recognition of life's fundamental ordinariness.

The poem also engages with the pastoral tradition, but with characteristic Shakespearean complexity. The natural imagery of wind and rain might typically evoke the peaceful rural world that pastoral literature celebrates, but Shakespeare uses these elements to suggest nature's indifference to human concerns. This subversion of pastoral conventions reflects the broader cultural shift toward a more complex understanding of the relationship between human society and the natural world.

The work's treatment of the ages of man theme connects it to a long tradition of medieval and Renaissance literature exploring life's stages. However, where such works typically emphasize growth, achievement, and the accumulation of wisdom, Shakespeare's version focuses on the progressive recognition of limitation and the persistent presence of forces beyond human control. This pessimistic revision of the traditional theme reflects the growing influence of skeptical philosophy and the declining confidence in human perfectibility that characterized the later Renaissance.

Biographical and Historical Resonances

While specific biographical connections must be approached cautiously, the poem's themes resonate with what scholars know of Shakespeare's personal circumstances around 1601-1602. The playwright was approaching middle age, had experienced the death of his son Hamnet, and was witnessing the aging of Queen Elizabeth and the uncertainty surrounding the succession. These personal and political circumstances may have contributed to the poem's preoccupation with time's passage and the limitations of human achievement.

The poem's emphasis on theatrical performance and its meta-dramatic conclusion also reflect Shakespeare's position as a working playwright dependent on public approval. The promise to "strive to please you every day" acknowledges the commercial realities of theatrical production while simultaneously suggesting that artistic creation, like natural phenomena, persists regardless of its reception. This dual awareness of art's commercial and transcendent dimensions characterizes much of Shakespeare's mature work.

The Song's Function within Twelfth Night

As the conclusion to Twelfth Night, the song serves multiple dramatic functions that illuminate its themes and intensify its emotional impact. The play's romantic complications and comic misunderstandings are resolved through conventional dramatic mechanisms, but the song suggests that such resolutions are temporary and artificial. The movement from the play's elaborate social world to the song's solitary speaker emphasizes the difference between theatrical happiness and lived experience.

The song's performer, Feste, embodies the poem's themes through his position as both insider and outsider to the play's social world. As a professional fool, he participates in the court's festivities while maintaining critical distance from its values and assumptions. This double perspective allows him to serve as both entertainer and commentator, much as the song itself functions as both conclusion and critique of the preceding drama.

The transition from the play's prose and blank verse to the song's ballad meter creates a shift in dramatic register that prepares the audience for the poem's philosophical content. The simpler, more direct language of the song contrasts sharply with the elaborate wordplay and complex plotting of the preceding scenes, suggesting that ultimate truths may be found in simple observations rather than clever manipulations.

Conclusion

"The Wind and the Rain" achieves its profound impact through the masterful integration of simple form with complex content. Shakespeare transforms a traditional ballad structure into a vehicle for sophisticated philosophical meditation, creating a work that speaks simultaneously to immediate emotional experience and universal human concerns. The poem's power lies not in its ability to provide answers or consolation but in its capacity to articulate the questions and anxieties that define human existence.

The song's final image of rain falling "every day" offers neither despair nor hope but simply acknowledgment—a recognition that existence continues regardless of human satisfaction or disappointment. This stance, neither optimistic nor pessimistic but simply observant, represents one of Shakespeare's most mature philosophical achievements. The poem suggests that wisdom consists not in overcoming life's difficulties but in learning to see them as natural and inevitable as weather.

In its combination of folk simplicity and philosophical sophistication, "The Wind and the Rain" exemplifies Shakespeare's unique ability to find universal significance in particular experience. The poem's enduring power derives from its capacity to transform personal disappointment into shared understanding, individual limitation into universal truth. Through its haunting refrain and inexorable progression, the song creates a space where audiences can contemplate their own experiences within the broader patterns of human existence, finding neither easy comfort nor bitter complaint but something more valuable: the recognition that they are not alone in their struggles with time, change, and the persistent indifference of the natural world.

The poem ultimately stands as a testament to the power of art to transform suffering into understanding, isolation into connection, and temporal experience into timeless truth. In its quiet acceptance of life's limitations and its gentle insistence on continuing despite them, "The Wind and the Rain" offers a model of mature wisdom that remains as relevant today as it was four centuries ago. The rain, indeed, continues to fall every day, but in Shakespeare's hands, even this simple fact becomes a source of profound artistic and philosophical illumination.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!