A Psalm of Life

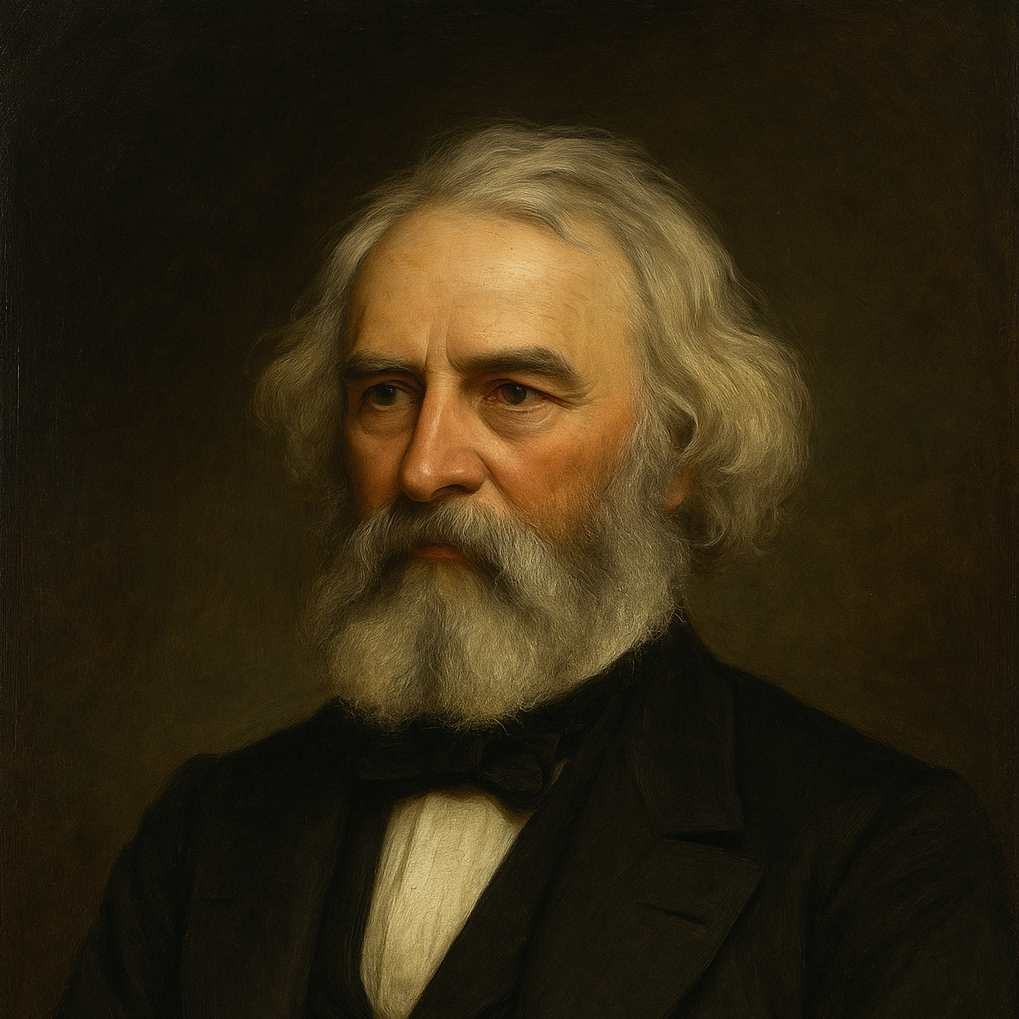

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

1807 to 1882

What the heart of the young man said to the Psalmist

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each tomorrow

Find us farther than today.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,—act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;—

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's A Psalm of Life

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "A Psalm of Life" is a poignant and inspiring work that encapsulates the poet's philosophy on the meaning and purpose of human existence. Written in 1838, this poem reflects the optimistic and action-oriented ethos of American Transcendentalism, a movement that emphasized individual potential and the importance of living life to its fullest.

The poem begins with a direct challenge to pessimistic views of life, rejecting the notion that "Life is but an empty dream!" This opening sets the tone for the entire work, positioning the speaker as a voice of youthful vigor and determination against the backdrop of more somber, fatalistic perspectives. Longfellow's use of exclamation marks throughout the poem underscores the urgency and passion of his message, creating a sense of imperative that propels the reader forward.

Central to the poem's theme is the idea that life is "real" and "earnest," not a mere illusion or prelude to death. This concept is reinforced by the biblical allusion to Genesis 3:19, "Dust thou art, to dust returnest," which Longfellow reinterprets to apply only to the physical body, not the soul. This distinction is crucial, as it establishes a framework for understanding life as more than just a journey towards inevitable mortality.

The poem's structure, consisting of nine quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme, gives it a rhythmic quality that mirrors the steady march of time and the beating of the human heart. This formal choice supports the content, particularly evident in lines like "Still, like muffled drums, are beating / Funeral marches to the grave." The musicality of the verse form contrasts with the gravity of the subject matter, creating a tension that reflects the complex nature of human existence.

Longfellow employs vivid metaphors throughout the poem to illustrate his ideas. The comparison of life to a "field of battle" and a "bivouac" (a temporary military encampment) emphasizes the struggles and transient nature of human existence. These martial images are juxtaposed with the exhortation to "Be a hero in the strife!" urging readers to face life's challenges with courage and determination.

The poem also grapples with the concept of time, acknowledging its fleeting nature while simultaneously emphasizing the enduring impact of human actions. The lines "Art is long, and Time is fleeting" encapsulate this duality, suggesting that while individual lives may be short, the legacy of human creativity and achievement can transcend temporal limitations.

Longfellow's work is deeply rooted in the American literary tradition, particularly in its emphasis on self-reliance and individual agency. The directive to "Trust no Future, howe'er pleasant! / Let the dead Past bury its dead!" echoes Ralph Waldo Emerson's philosophy of living in the present and taking personal responsibility for one's life. This focus on action and self-determination is a hallmark of American Transcendentalism and reflects the broader cultural ethos of 19th-century America.

The poem's most enduring image is perhaps that of the "Footprints on the sands of time," a metaphor that has since entered common parlance. This powerful visual represents the lasting impact of a life well-lived, suggesting that our actions can inspire and guide future generations. The nautical imagery of life as a "solemn main" and the reference to a "forlorn and shipwrecked brother" extend this metaphor, portraying life as a vast ocean and humanity as fellow travelers who can draw strength from the examples set by others.

In its concluding stanza, "A Psalm of Life" synthesizes its various themes into a call to action. The exhortation to be "up and doing, / With a heart for any fate" encapsulates the poem's central message of active engagement with life, regardless of circumstances. The final line, "Learn to labor and to wait," introduces a note of patience and perseverance, suggesting that meaningful achievement requires both diligent effort and the wisdom to recognize that results may not be immediate.

Longfellow's "A Psalm of Life" stands as a testament to the power of poetry to inspire and motivate. Its enduring popularity lies in its ability to address universal human concerns about the meaning of life and the legacy we leave behind. Through its skillful use of language, rhythm, and imagery, the poem offers a compelling vision of life as a precious opportunity for action, growth, and positive influence on others. In doing so, it continues to resonate with readers, encouraging them to approach life with purpose, courage, and an awareness of their potential to make a lasting impact on the world.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!