Winds of May, that dance on the sea

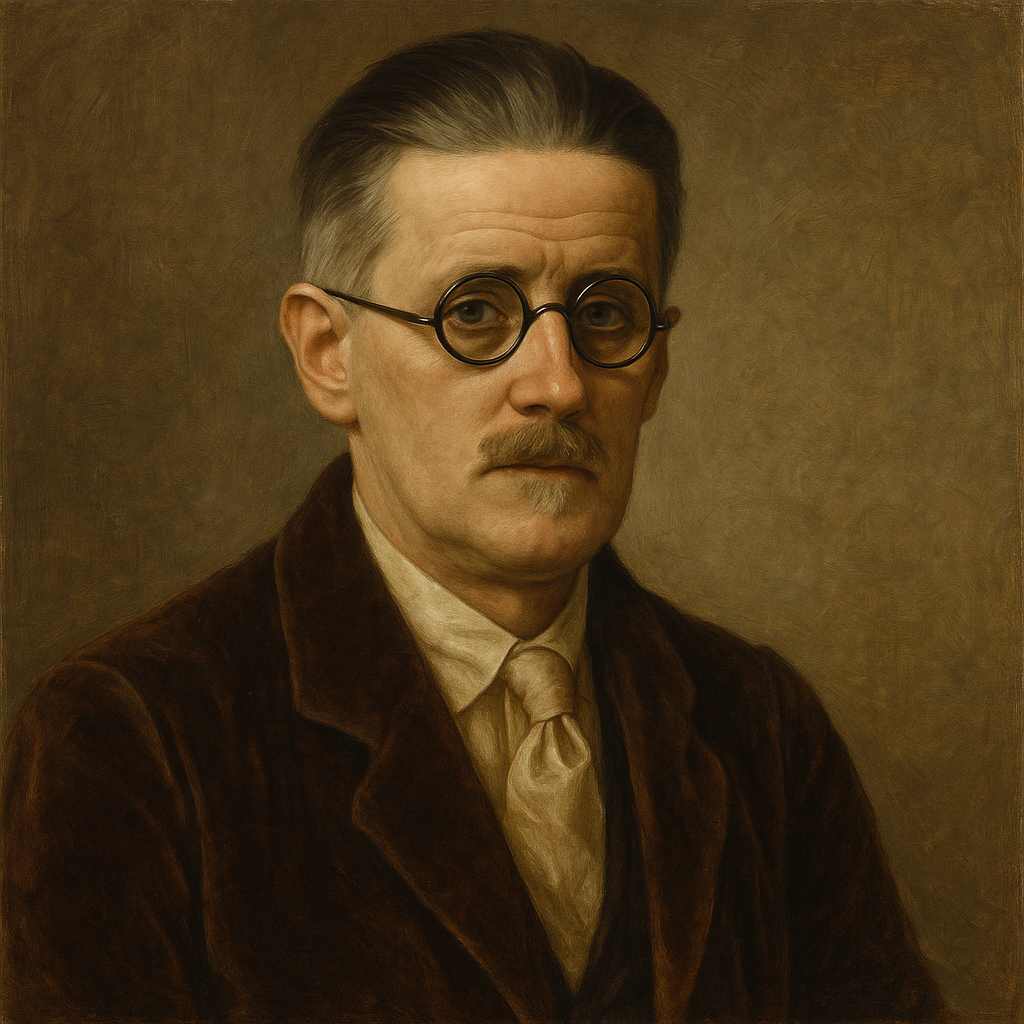

James Joyce

1882 to 1941

Winds of May, that dance on the sea,

Dancing a ring-around in glee

From furrow to furrow, while overhead

The foam flies up to be garlanded,

In silvery arches spanning the air,

Saw you my true love anywhere?

Welladay! Welladay!

For the winds of May!

Love is unhappy when love is away!

James Joyce's Winds of May, that dance on the sea

James Joyce, best known for his groundbreaking modernist novels Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, was also a poet whose lyrical works often reflect the same preoccupations with love, loss, and the passage of time that dominate his prose. “Winds of May, that dance on the sea” is a deceptively simple poem that encapsulates these themes within a brief but evocative structure. At first glance, the poem appears to be a lighthearted invocation of spring and love, yet beneath its musical cadence lies a profound meditation on absence and longing. Through its interplay of natural imagery, rhythmic vitality, and emotional depth, the poem exemplifies Joyce’s ability to distill complex human emotions into concise, resonant verse.

This essay will explore the poem’s thematic concerns, its use of literary devices, and its place within Joyce’s broader oeuvre. Additionally, it will consider the historical and biographical context in which the poem was written, as well as its philosophical underpinnings, particularly in relation to the transient nature of joy and the inevitability of separation. By examining these elements, we can appreciate how Joyce transforms a seemingly straightforward lyric into a poignant reflection on love’s fragility.

Themes: Love, Absence, and the Ephemeral

The central theme of “Winds of May, that dance on the sea” is the sorrow of separation. The speaker addresses the “Winds of May,” personifying them as joyful dancers moving across the sea, and asks if they have seen his “true love.” The poem’s shift from exuberant natural imagery to lamentation underscores the contrast between the vitality of the season and the speaker’s personal grief. May, traditionally associated with renewal and romance, becomes ironic here—the winds may dance in “glee,” but the speaker is left in despair.

The final lines, “Welladay! Welladay! / For the winds of May! / Love is unhappy when love is away!” reinforce this emotional tension. The exclamation “Welladay!”—an archaic expression of sorrow—heightens the sense of melancholy, suggesting that even the most vibrant forces of nature cannot alleviate the pain of absence. This theme of love’s impermanence is recurrent in Joyce’s work; in Chamber Music, his early collection of poems, many pieces similarly explore the fleeting nature of romantic happiness.

Literary Devices: Music, Imagery, and Personification

Joyce’s background as a musician profoundly influenced his poetic style, and “Winds of May” is deeply musical in its rhythm and sound patterns. The repetition of the “d” sound in “dance,” “dancing,” and “glee” creates a lively, almost waltz-like movement, mirroring the winds’ carefree motion. The alliteration in “foam flies up to be garlanded” enhances the poem’s lyrical quality, while the assonance in “silvery arches spanning the air” lends it a flowing, melodic tone.

The imagery is equally rich, blending the visual and the kinetic. The “foam” flying up to be “garlanded” suggests a natural coronation, as if the sea itself is celebrating May’s arrival. The “silvery arches” evoke both the spray of waves and perhaps even a bridal arch, subtly reinforcing the theme of love. Yet this beauty is undercut by the speaker’s unanswered question: “Saw you my true love anywhere?” The winds, though animate and responsive in their dance, remain indifferent to human suffering.

Personification is central to the poem’s effect. The winds are not merely elements of nature but active participants in a “ring-around,” a childlike game that contrasts with the speaker’s adult sorrow. This technique aligns with Romantic and Symbolist traditions, where nature often reflects or opposes human emotion. Unlike Wordsworth’s pantheistic visions, however, Joyce’s personification here serves to emphasize nature’s indifference—the May winds dance on, oblivious to the lover’s plight.

Historical and Biographical Context

“Winds of May” was published in Chamber Music (1907), Joyce’s first collection of poetry, written during his early twenties while he was living in self-imposed exile from Ireland. The poems in this volume are often seen as less radical than his later works, yet they reveal his preoccupation with themes of exile, unfulfilled desire, and artistic idealism.

Biographically, the poem may reflect Joyce’s own romantic frustrations. At the time of writing, he was deeply in love with Nora Barnacle, whom he had recently met and who would later become his lifelong partner. Their relationship was marked by Joyce’s intense emotional dependence, and the fear of losing her—whether through separation or betrayal—recurs in his writings. The speaker’s plaintive cry in “Winds of May” could thus be read as an expression of Joyce’s own anxieties about love’s precariousness.

Additionally, the poem’s invocation of May carries cultural significance. In Irish tradition, May (Bealtaine) was a time of both celebration and superstition, associated with fertility but also with supernatural dangers. The poem’s juxtaposition of joy and sorrow may subtly echo these folkloric dualities.

Philosophical and Comparative Readings

The poem’s exploration of transience invites comparison with the carpe diem tradition, though with a more melancholic tone. Unlike Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” which urges immediate pleasure in the face of time’s passage, Joyce’s poem laments time’s indifference. The winds of May are fleeting, just as love’s presence is ephemeral—when love is “away,” happiness dissipates.

Philosophically, the poem resonates with Schopenhauer’s idea that desire is inherently linked to suffering. The speaker’s longing is what defines his emotional state; even the vibrant May winds cannot compensate for his loss. This aligns with Joyce’s broader modernist sensibility, where fulfillment is often deferred or unattainable.

A comparative reading with Yeats’s early poetry, particularly “The Song of Wandering Aengus,” reveals shared themes of longing and natural symbolism. Yet where Yeats’s speaker pursues a mystical, almost mythical love, Joyce’s is grounded in personal absence, underscoring modernism’s shift from the transcendent to the psychological.

Conclusion: The Emotional Power of Concision

Though brief, “Winds of May, that dance on the sea” is a masterful example of how Joyce condenses profound emotion into a compact form. Its musicality, vivid imagery, and thematic depth make it a microcosm of his larger concerns—love’s joys and sorrows, the passage of time, and the artist’s struggle to reconcile beauty with loss.

The poem’s enduring appeal lies in its universality. Anyone who has experienced separation or unrequited love can recognize the speaker’s plaintive cry. Joyce reminds us that even in the midst of nature’s most exuberant displays, human loneliness persists. The winds may dance, but the heart still aches—and in that tension, the poem finds its power.

In the end, “Winds of May” is not just a lament but a testament to poetry’s ability to give voice to sorrow. Like the foam lifted by the wind, the poem itself becomes a “garland,” a fleeting yet beautiful tribute to love’s enduring, if painful, presence in our lives.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!