Sumer is icumen in (Middle English)

W. de Wycombe

1270 to 1330

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Groweþ sed

and bloweþ med

and springþ þe wde nu

Sing cuccu

Awe bleteþ after lomb

lhouþ after calue cu

Bulluc sterteþ

bucke uerteþ

murie sing cuccu

Cuccu cuccu

Wel singes þu cuccu

ne swik þu nauer nu

Sing cuccu nu; Sing cuccu.

Sing cuccu; Sing cuccu nu

W. de Wycombe's Sumer is icumen in

Introduction

The Middle English lyric "Sumer is icumen in" stands as a testament to the vibrant oral tradition of medieval England and serves as a crucial landmark in the development of English poetry and music. Composed in the mid-13th century, this piece is not only one of the oldest examples of English secular music but also a sophisticated exploration of the interplay between nature, human experience, and linguistic innovation. This essay will delve into the multifaceted aspects of the poem, examining its formal structure, thematic content, linguistic features, and cultural significance.

Historical Context and Manuscript Tradition

Before delving into the intricacies of the poem itself, it is crucial to understand its historical context. "Sumer is icumen in" is preserved in a manuscript known as the Reading Rota (Harley 978), housed in the British Library. The manuscript, dated to around 1261, was likely compiled at Reading Abbey. This provenance is significant, as it situates the poem within a monastic tradition that, contrary to popular belief, was not solely focused on religious texts but also engaged with secular works.

The poem's survival in this form is remarkable, as it includes not only the lyrics but also musical notation. This makes it an invaluable resource for musicologists studying the development of polyphonic music in England. The fact that it was written down at all suggests that it was considered worthy of preservation, perhaps due to its popularity or its innovative musical structure.

Formal Structure and Musical Elements

"Sumer is icumen in" is structured as a round, also known as a rota. This musical form allows for multiple voices to sing the same melody at staggered intervals, creating a complex harmonic texture. The poem consists of two main parts: the principal voice (which begins "Sumer is icumen in") and the "pes" or ground (which repeats "Sing cuccu nu"). This structure reflects a sophisticated understanding of musical composition, blending the simplicity of a folk song with the complexity of polyphonic arrangement.

The use of the round form is not merely a musical choice but also serves a poetic function. The circular nature of the round mirrors the cyclical patterns of nature described in the poem, creating a formal echo of the thematic content. This integration of form and content demonstrates a level of artistic sophistication that belies the poem's apparent simplicity.

Thematic Analysis: The Celebration of Nature and Renewal

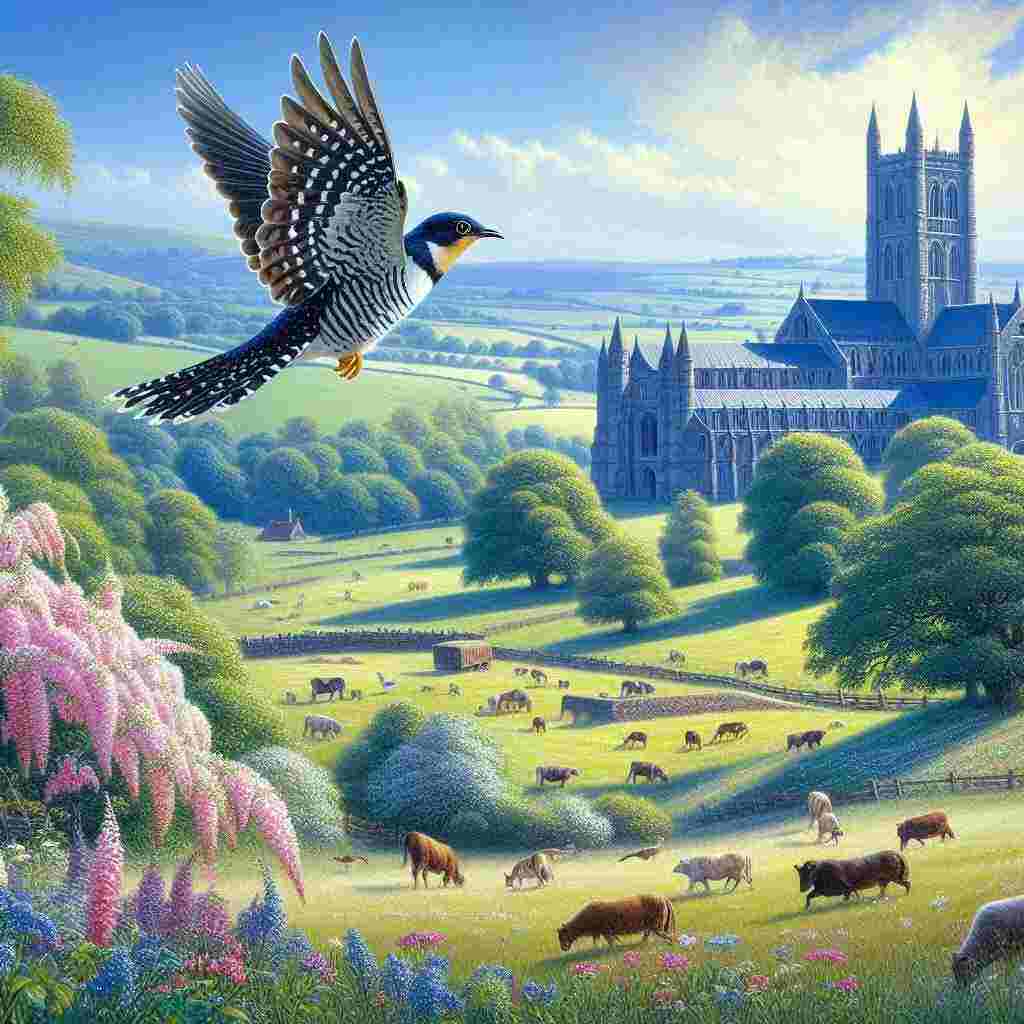

At its core, "Sumer is icumen in" is a celebration of the arrival of summer and the renewal of life that accompanies it. The poem vividly portrays a pastoral scene, teeming with the sights and sounds of nature in full bloom. The opening line, "Sumer is icumen in" (Summer has come in), immediately sets the tone of joyous announcement.

The subsequent lines paint a picture of natural abundance and fertility:

"Groweþ sed" (The seed grows) "and bloweþ med" (and the meadow blooms) "and springþ þe wde nu" (and the wood springs anew)

This progression from seed to meadow to wood creates a sense of expanding life, moving from the microscopic to the macroscopic. The use of active verbs ("groweþ," "bloweþ," "springþ") imbues the scene with dynamism and vitality.

The poem then shifts focus to the animal world, describing a series of creatures and their offspring:

"Awe bleteþ after lomb" (The ewe bleats after the lamb) "lhouþ after calue cu" (The cow lows after the calf) "Bulluc sterteþ" (The bullock leaps) "bucke uerteþ" (The buck farts)

This catalogue of animals serves multiple purposes. First, it continues the theme of fertility and new life, emphasizing the reproductive cycle that summer brings. Second, it grounds the poem in the everyday realities of rural life, making it relatable to a wide audience. Third, the inclusion of both domestic (ewe, cow) and wild (buck) animals suggests a harmonious coexistence of human and natural worlds.

The repeated refrain "Sing cuccu" (Sing, cuckoo) ties these elements together. The cuckoo, with its distinctive call, is a harbinger of spring in European folklore. Its presence in the poem serves as both a naturalistic detail and a symbolic representation of renewal and cyclical time.

Linguistic Analysis: Middle English and the Evolution of Language

From a linguistic perspective, "Sumer is icumen in" offers a fascinating glimpse into the state of the English language in the mid-13th century. The poem is written in Middle English, specifically the West Saxon dialect, and showcases several features characteristic of this stage in the language's development.

One notable aspect is the retention of inflectional endings, such as the "-eþ" in "groweþ" and "bleteþ." These endings, remnants of Old English's more complex grammatical system, were already beginning to erode by this time. Their presence in the poem reflects a transitional stage in the language's evolution.

The vocabulary of the poem is predominantly Germanic in origin, with words like "sumer" (summer), "sed" (seed), and "cu" (cow) showing clear connections to their modern English counterparts. However, we also see the influence of Old Norse in words like "sterteþ" (starts, leaps), reflecting the linguistic impact of Viking invasions centuries earlier.

The spelling conventions in the poem are not yet standardized, a common feature of Middle English texts. For example, the word "cuckoo" appears as both "cuccu" and "cuccú," illustrating the fluid nature of orthography at this time.

Perhaps most intriguing is the use of the letter þ (thorn), representing the "th" sound. This letter, borrowed from the runic alphabet, was common in Old and Middle English but eventually fell out of use. Its presence in this poem serves as a visual reminder of the language's complex history and the multitude of influences that shaped it.

Cultural Significance and Literary Legacy

"Sumer is icumen in" occupies a unique position in English literary history. As one of the earliest surviving examples of secular lyric poetry in English, it provides a crucial link between the Old English poetic tradition and the flowering of Middle English literature that would follow in the works of poets like Chaucer.

The poem's celebration of nature and the changing seasons places it within a long tradition of pastoral poetry that stretches back to classical antiquity and continues to the present day. However, its distinctly English setting and references make it an important early example of a vernacular pastoral tradition.

The poem's enduring popularity is evidenced by its continued presence in anthologies and its numerous modern translations and adaptations. Its simple yet evocative imagery and catchy refrain have made it accessible to audiences across centuries, while its linguistic and formal complexities continue to engage scholars.

Conclusion

"Sumer is icumen in" stands as a remarkable artifact of medieval English culture, bridging the worlds of poetry, music, and linguistic history. Its celebration of nature's renewal, expressed through vivid imagery and innovative form, continues to resonate with readers and listeners today. As a window into the language, culture, and artistic sensibilities of 13th-century England, it offers invaluable insights for scholars across multiple disciplines.

The poem's enduring appeal lies in its ability to capture a universal human experience—the joy of summer's arrival—in a way that is both culturally specific and broadly relatable. It reminds us that, despite the vast changes in language and society over the past eight centuries, the fundamental rhythms of nature and human response to them remain constant.

In its fusion of sophisticated artistry with folk traditions, its blending of sacred and secular elements, and its capturing of a language in transition, "Sumer is icumen in" encapsulates many of the complexities and contradictions of medieval culture. It stands as a testament to the richness and vitality of English literary tradition, inviting continued exploration and appreciation from each new generation of readers and scholars.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!