1 Poems by William Watson

1858 - 1935

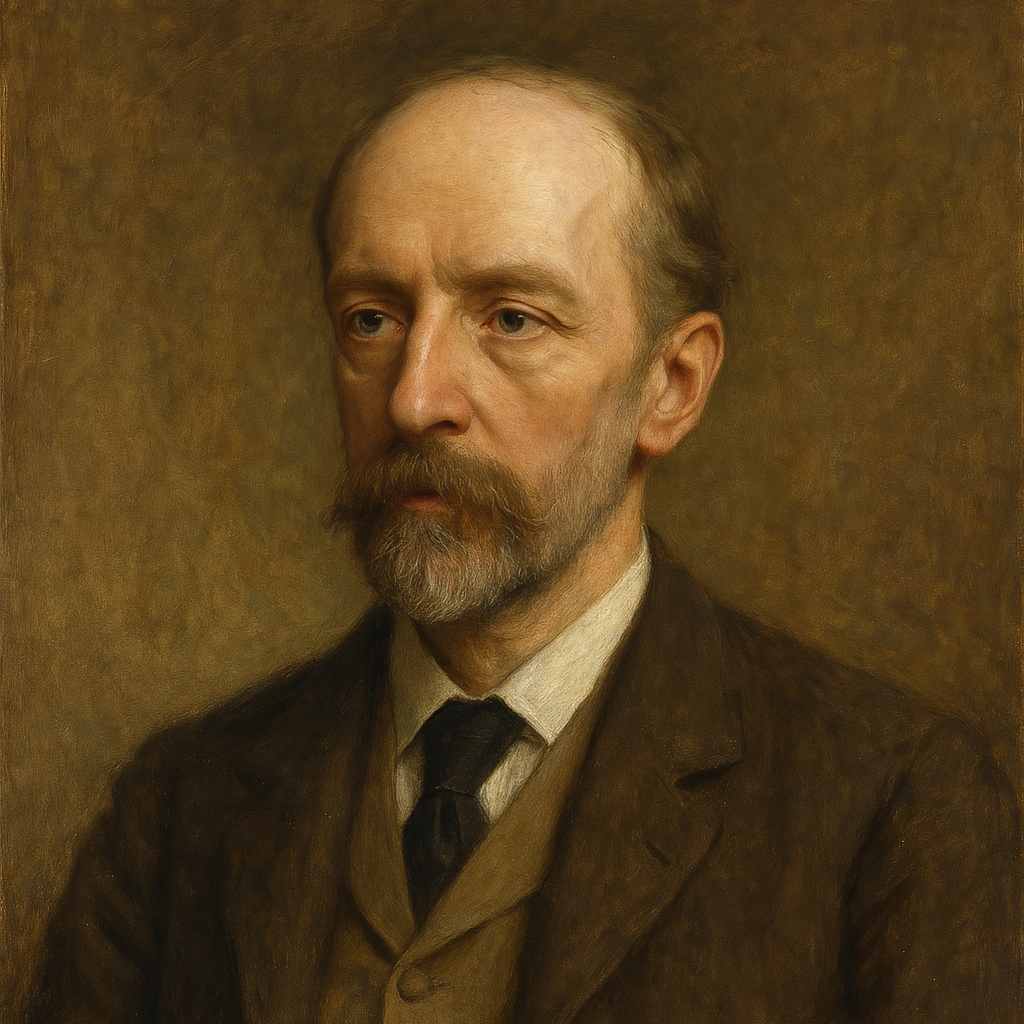

William Watson Biography

William Watson, a largely forgotten figure in the annals of English poetry, was born on August 2, 1858, in Burley-in-Wharfedale, Yorkshire. His life and work spanned a critical period in British literary history, bridging the gap between the late Victorian era and the early modernist movement. Despite his initial acclaim and prolific output, Watson's legacy has been overshadowed by his more famous contemporaries, making him a fascinating subject for literary scholars seeking to understand the complexities of poetic reputation and the vagaries of literary fashion.

Watson's early years were marked by a precocious talent for verse. Raised in Liverpool, where his family moved shortly after his birth, he was educated at Liverpool College. However, much of his poetic education was self-directed, as he immersed himself in the works of Wordsworth, Shelley, and Keats. This autodidactic approach would shape his poetic sensibilities, leading him to develop a style that blended Romantic influences with a distinctly Victorian sensibility.

His first collection, "The Prince's Quest and Other Poems," was published in 1880 when Watson was just 22 years old. While it did not immediately catapult him to fame, it did establish him as a promising new voice in English poetry. The titular poem, a long narrative work, showcased Watson's ability to craft intricate, lyrical verse within traditional forms. This early work also hinted at themes that would become central to his oeuvre: the tension between idealism and reality, the power of nature, and the role of the poet in society.

Watson's reputation grew steadily throughout the 1880s and 1890s, with the publication of several well-received collections, including "Wordsworth's Grave and Other Poems" (1890) and "Lachrymae Musarum" (1892). The former, in particular, garnered significant attention for its eloquent tribute to one of Watson's poetic idols. His precise diction, masterful use of form, and ability to engage with both contemporary issues and timeless themes earned him comparisons to Tennyson, who was nearing the end of his tenure as Poet Laureate.

Indeed, when Tennyson died in 1892, many literary figures and critics championed Watson as his natural successor. However, the laureateship ultimately went to Alfred Austin, a decision that deeply disappointed Watson and marked a turning point in his career. This professional setback coincided with personal struggles, as Watson battled with mental health issues that would plague him throughout his life.

Despite these challenges, Watson continued to produce poetry of notable quality. His work from this period, including "The Father of the Forest and Other Poems" (1895) and "The Hope of the World and Other Poems" (1897), showcased a maturing voice that increasingly grappled with political and social issues. Watson was not afraid to court controversy, as evidenced by his poem "The Woman with the Serpent's Tongue," widely believed to be a scathing critique of Margot Asquith, wife of the Liberal politician H. H. Asquith.

Watson's political engagement extended beyond his poetry. He was a vocal critic of British imperialism, particularly during the Second Boer War, a stance that likely cost him the laureateship when it again became vacant in 1896. His opposition to imperialism and his support for Irish Home Rule were expressed in poems such as "For England" and "The Year of Shame," which demonstrated his willingness to use his art as a vehicle for social commentary.

As the new century dawned, Watson found himself increasingly out of step with emerging modernist trends in poetry. His adherence to traditional forms and his belief in the moral and didactic function of poetry put him at odds with the experimental works of poets like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Nevertheless, he continued to write and publish, producing collections such as "New Poems" (1909) and "The Muse in Exile" (1913).

Watson's personal life was as complex as his professional one. He married Adeline Maureen Pring in 1909, at the age of 51. The marriage produced two children but was reportedly strained by Watson's recurring mental health issues and financial difficulties. Despite these challenges, Watson found solace and inspiration in his family life, as evidenced by the tender domestic poems that appeared in his later collections.

The latter part of Watson's career was marked by a gradual decline in his literary reputation. While he continued to write and publish, his work no longer commanded the attention it once had. The changing literary landscape, coupled with Watson's own reluctance to adapt his style, led to a diminishing readership. However, this period also saw Watson produce some of his most introspective and philosophically rich work, as he reflected on aging, legacy, and the role of art in a rapidly changing world.

William Watson died on August 13, 1935, in Ditchling, Sussex. At the time of his death, he had largely faded from public consciousness, a far cry from the days when he was considered a potential Poet Laureate. Yet his body of work, spanning over five decades, remains a testament to a poet deeply engaged with his craft and his times.

In retrospect, Watson's career offers a compelling case study in the vicissitudes of literary fame and the challenges faced by artists in periods of radical cultural change. His steadfast commitment to traditional poetic forms and his belief in the moral purpose of poetry set him apart from his modernist contemporaries, but also contributed to his eventual obscurity. For modern scholars, Watson's work provides valuable insights into the transition from Victorian to modernist poetry, the political and social concerns of late 19th and early 20th century Britain, and the complex interplay between an artist's personal life and their creative output.

While William Watson may not occupy the same hallowed place in the canon as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to English poetry is significant and worthy of reappraisal. His technical skill, his engagement with the issues of his day, and his unwavering belief in the power of poetry to enlighten and inspire continue to offer rich material for literary study and appreciation. In the end, Watson's life and work serve as a poignant reminder of the enduring value of poetic craft, even in the face of changing tastes and the inexorable march of literary history.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!