1 Poems by Alphonse de Lamartine

1790 - 1869

Alphonse de Lamartine Biography

Alphonse de Lamartine (1790–1869), a towering figure of French Romanticism, was a poet, statesman, and historian whose literary achievements and political vision shaped 19th-century France. His life embodied the idealism and complexity of his era, reflecting both the soaring aspirations of Romanticism and the turbulent sociopolitical changes sweeping Europe. As a poet, Lamartine infused his verses with deeply personal emotion, a profound engagement with nature, and a longing for transcendence that captivated readers across generations. As a public figure, his efforts to reconcile poetic ideals with political realities offer a compelling study in the interplay of art and power.

Lamartine was born on October 21, 1790, in Mâcon, Burgundy, into a family of minor nobility. His upbringing, steeped in Catholic faith and a sense of aristocratic heritage, deeply influenced his early worldview. The French Revolution, however, disrupted his family’s fortunes, leaving an indelible mark on the young Alphonse. While his parents remained staunch royalists, Lamartine’s political views evolved over time, moving toward liberal republicanism—a shift that would define his later public life. Educated in Jesuit schools and influenced by classical literature, he demonstrated early literary promise. Yet it was his encounter with nature in the pastoral landscapes of his childhood that left a more enduring imprint on his imagination. These landscapes became the backdrop against which his poetic sensibilities matured.

Lamartine’s formative years were shaped by both privilege and precarity. He traveled to Italy in 1811, an experience that broadened his cultural horizons and deepened his appreciation for art and history. It was during this period that he began to explore poetry in earnest. In the tradition of Romantic poets, Lamartine viewed art as a vehicle for emotional and spiritual exploration. His literary ambitions were briefly interrupted by his military service during the Bourbon Restoration, but his profound dissatisfaction with the rigid structures of the French army further fueled his Romantic idealism and disdain for conventional authority.

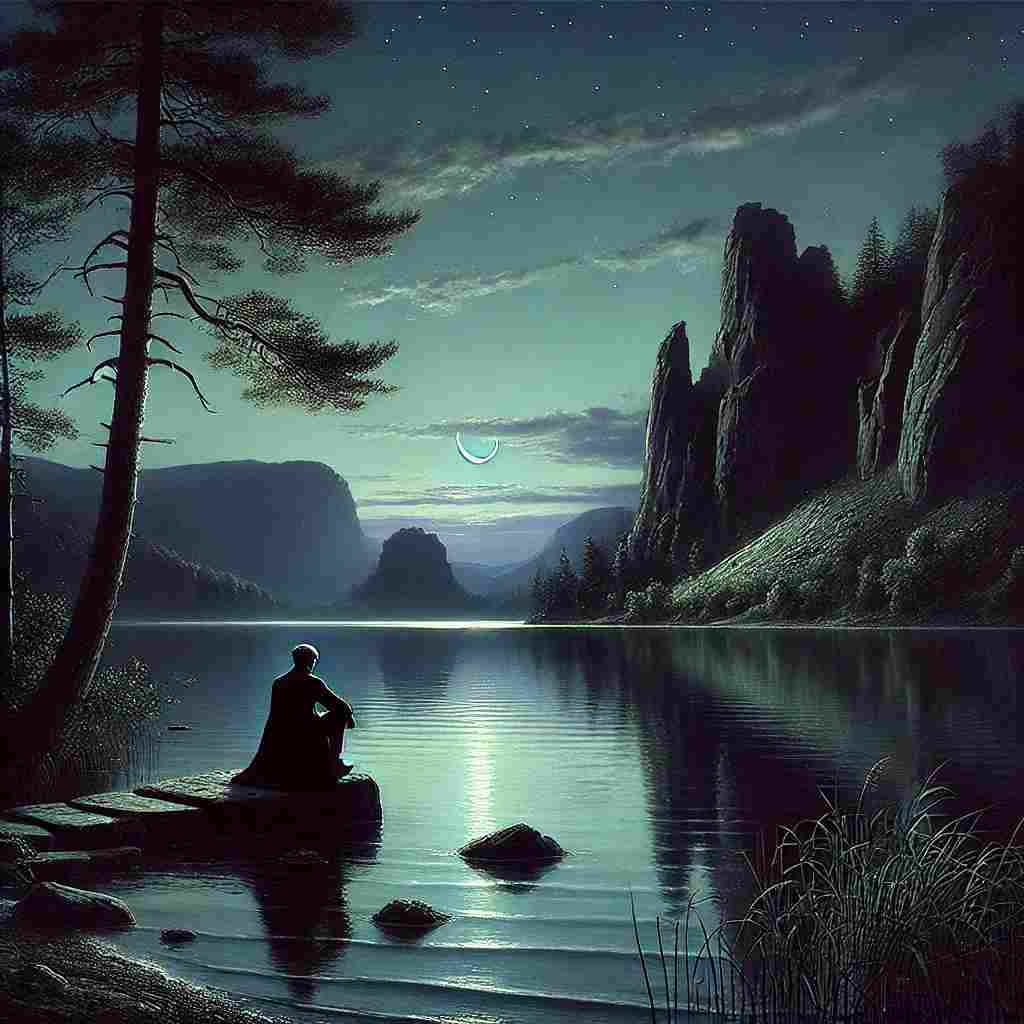

The publication of Méditations poétiques in 1820 marked Lamartine’s emergence as a major literary figure. This collection of 24 poems established him as one of the pioneers of French Romanticism, alongside contemporaries such as Victor Hugo and Alfred de Vigny. The Méditations were a radical departure from the Neoclassical tradition that had dominated French poetry, favoring instead a deeply introspective and emotive style. Lamartine’s verses resonated with readers through their fusion of personal anguish, spiritual yearning, and reverence for nature. Poems like “Le Lac” exemplified his ability to transform personal loss—specifically, the death of Julie Charles, his beloved—into a universal meditation on time, memory, and the fleeting nature of human happiness. His use of flowing, musical language and vivid imagery marked a new era in French poetry, one that privileged the subjective and the sublime over rigid formality.

Nature played a central role in Lamartine’s oeuvre, not merely as a setting but as an active presence imbued with divine significance. His works often reflect a pantheistic vision, where landscapes serve as mirrors to human emotion and conduits to the infinite. This spiritual dimension of his poetry set him apart from his peers, imbuing his work with a sense of cosmic wonder that resonated deeply in an age marked by industrialization and scientific progress.

Lamartine’s literary successes were complemented by a burgeoning political career. Deeply influenced by his travels to the Near East in the early 1830s, he returned to France with a broadened perspective on religion, culture, and politics. His sojourns in places like Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey reinforced his belief in the universality of human experience and the potential for cultural and spiritual synthesis. These ideas informed both his poetry and his political thought, as he increasingly advocated for humanitarianism, democracy, and social reform.

Elected to the French Chamber of Deputies in 1833, Lamartine brought his idealistic vision to the political stage. His speeches, marked by the same lyrical eloquence as his poetry, called for the abolition of slavery, the expansion of civil liberties, and the establishment of a more egalitarian society. He was a committed republican, believing in the possibility of a government that balanced liberty with fraternity—a vision he sought to realize during the Revolution of 1848.

The events of 1848 represented the pinnacle of Lamartine’s political career. As the February Revolution overthrew the monarchy of Louis-Philippe, Lamartine emerged as a leading figure in the Provisional Government. His role in crafting the Second Republic was characterized by an effort to navigate the competing demands of radical revolutionaries, moderate reformers, and conservative factions. Though his tenure was short-lived, his eloquent defense of the tricolor flag—opposed by radicals who sought to adopt the red flag as a symbol of the revolution—underscored his commitment to a vision of France rooted in continuity as well as change.

Lamartine’s political idealism, however, was not matched by practical success. His failure to address the economic crises facing the Republic, combined with his perceived detachment from the realities of governance, led to his political downfall. After a crushing defeat in the presidential elections of December 1848, he withdrew from active politics, retreating into a life of financial difficulty and relative obscurity. His later years were marked by a prolific output of historical and autobiographical works, including his ambitious Histoire des Girondins (1847), which contributed to the mythologizing of the French Revolution and influenced revolutionary sentiment.

Despite the decline of his political influence, Lamartine’s literary legacy endured. His later poetry, though less celebrated than his early works, reflects a deepening preoccupation with philosophical and religious themes. In works such as Jocelyn (1836) and La Chute d’un ange (1838), he explored questions of human destiny, divine providence, and the possibility of redemption. These epic narratives, though less immediate in their emotional impact than his lyrical poetry, reveal the breadth of his intellectual and artistic ambitions.

Lamartine’s influence on subsequent generations of poets and thinkers cannot be overstated. His emphasis on personal emotion and the sublime beauty of nature paved the way for later Romantic and Symbolist poets, while his efforts to integrate literature with social and political engagement anticipated the commitments of figures like Victor Hugo. At the same time, his failures—both personal and political—serve as a poignant reminder of the tensions between idealism and reality, art and action.

By the time of his death on February 28, 1869, Lamartine had become a symbol of Romanticism’s triumphs and contradictions. His life and work offer a testament to the enduring power of poetry to capture the complexities of the human spirit, even as it grapples with the imperatives of a changing world. In Lamartine’s vision, the poet is not merely a chronicler of beauty or a witness to history, but a guide to the higher truths that lie beyond the immediate and the visible. This legacy, at once deeply personal and profoundly universal, ensures his place among the great figures of world literature.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!