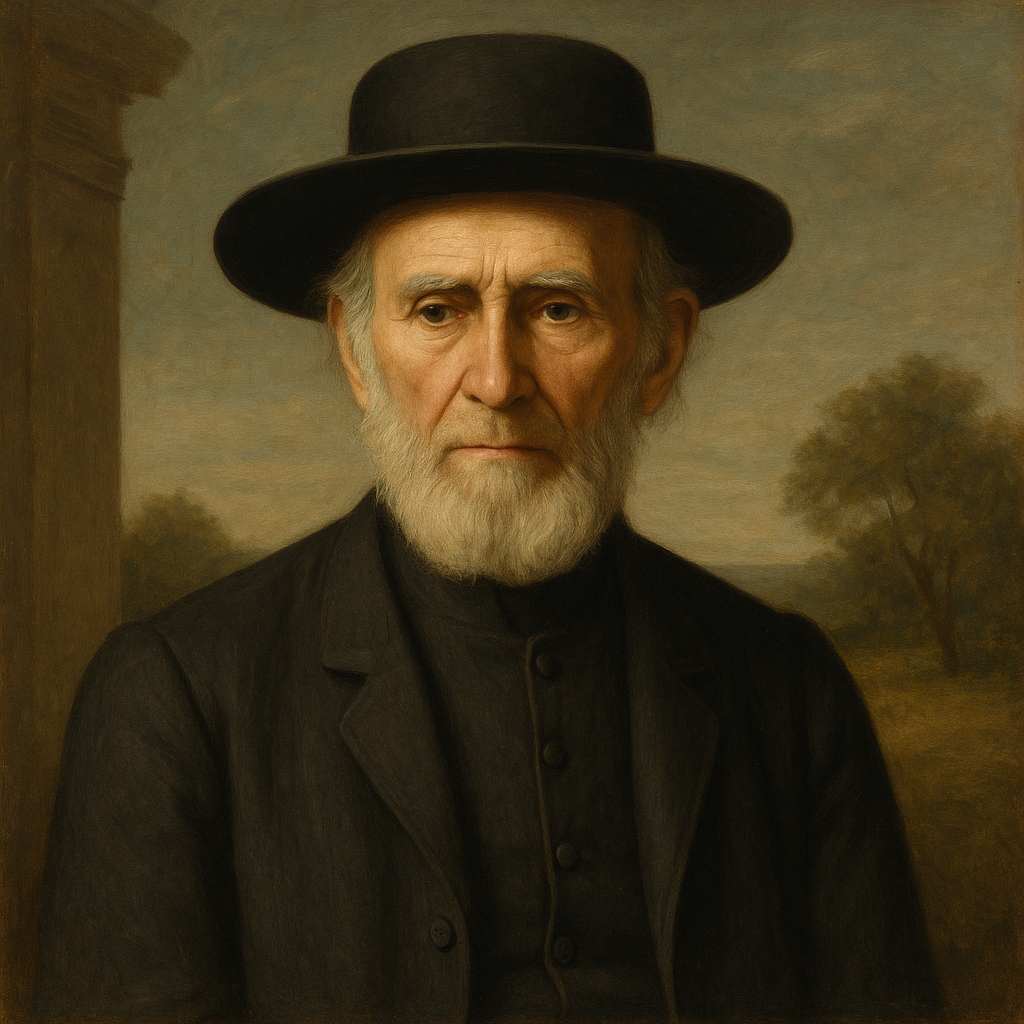

2 Poems by John Greenleaf Whittier

1807 - 1892

John Greenleaf Whittier Biography

John Greenleaf Whittier, born on December 17, 1807, in Haverhill, Massachusetts, emerged as one of the most influential American poets of the 19th century. His life and work spanned a period of profound social and political change in the United States, and his poetry played a significant role in shaping public opinion on issues such as slavery, human rights, and social justice.

Whittier's upbringing in a Quaker family on a modest farm in rural Massachusetts deeply influenced his worldview and his literary output. The values of simplicity, pacifism, and equality that were central to Quaker teaching became foundational elements of his poetry and his social activism. His early education was limited, but he possessed a voracious appetite for learning, devouring whatever books he could access, including borrowed volumes of poetry that sparked his own poetic ambitions.

The young Whittier's talent for verse was first recognized when his sister secretly submitted one of his poems to the Newburyport Free Press, edited by William Lloyd Garrison. This event marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship between Whittier and Garrison, and it set Whittier on the path to becoming not just a poet, but a powerful voice in the abolitionist movement.

Whittier's early career was marked by a dual commitment to poetry and journalism. He worked as a newspaper editor in Boston and Hartford, using his platform to advocate for social reform and to hone his writing skills. His first collection of poems, "Legends of New England in Prose and Verse" (1831), demonstrated his interest in local history and folklore, themes that would recur throughout his career.

However, it was Whittier's involvement in the abolitionist movement that truly defined his early work and established his reputation as a poet of moral conviction. His anti-slavery poems, collected in works such as "Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States" (1837) and "Voices of Freedom" (1846), were powerful calls to action that helped galvanize public opinion against slavery. Poems like "Ichabod," a scathing critique of Daniel Webster's support for the Fugitive Slave Act, showcased Whittier's ability to use verse as a weapon in the fight for social justice.

Whittier's poetry from this period is characterized by its moral fervor, its direct address to the reader, and its use of biblical imagery and language. While these works may sometimes lack the subtlety of his later poetry, they possess a raw power and urgency that made them effective tools in the abolitionist cause. Whittier was not afraid to name names and confront powerful figures, earning him both admirers and enemies.

As the Civil War approached and then engulfed the nation, Whittier's poetry took on a new dimension. While he continued to write about slavery and emancipation, his work also began to explore themes of patriotism, sacrifice, and national unity. Poems like "Barbara Frietchie" became popular rallying cries, celebrating acts of courage and defiance in the face of war.

After the Civil War, Whittier's poetry underwent a significant shift. While he never abandoned his commitment to social justice, his work became more reflective, focusing on New England rural life, personal memories, and spiritual themes. It was during this period that he produced some of his most enduring and beloved works, including "Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl" (1866).

"Snow-Bound" is widely considered Whittier's masterpiece, a long narrative poem that paints a vivid picture of a New England family trapped by a snowstorm. The poem's detailed descriptions of rural life, its warm evocation of family and community, and its meditations on memory and the passage of time struck a chord with readers seeking comfort and nostalgia in the aftermath of the Civil War. The poem's success established Whittier as one of the most popular poets of his day and secured his financial independence.

Whittier's later work continued to explore themes of nature, spirituality, and New England life. Poems like "The Barefoot Boy" and "Telling the Bees" showcase his ability to capture the essence of rural experiences and traditions. His religious poetry, influenced by his Quaker faith, emphasizes personal spiritual experience over dogma, as seen in works like "The Eternal Goodness."

Throughout his career, Whittier's style evolved from the forceful rhetoric of his abolitionist verse to a more measured, contemplative tone. His later poems are characterized by their simplicity, their emotional directness, and their skillful use of natural imagery. While not as formally innovative as some of his contemporaries, Whittier's work is noted for its clarity, its moral center, and its deep connection to American landscape and culture.

Whittier's influence extended beyond his poetry. He was a respected voice in American letters, corresponding with other major literary figures and helping to shape the canon of American literature. His work in collecting and preserving New England folklore and his interest in local history also made significant contributions to the cultural life of the region.

In his later years, Whittier became something of a national institution, revered as a link to the country's past and as a moral exemplar. His 70th and 80th birthdays were celebrated as national events, testament to the esteem in which he was held. When he died on September 7, 1892, he was mourned as one of the last great figures of America's antebellum literary culture.

John Greenleaf Whittier's legacy is complex. While his abolitionist poetry played a crucial role in the fight against slavery, some of these works have not aged well stylistically. However, his later poetry, with its evocations of New England life and landscape, continues to be appreciated for its quiet beauty and emotional depth. Poems like "Snow-Bound" remain part of the American literary canon, studied in schools and beloved by readers.

Whittier's life and work offer a unique window into 19th-century American culture, spanning as they do the period from the early republic to the Gilded Age. His poetry reflects the major social and political movements of his time, from abolitionism to post-war reconciliation, while also capturing the essence of New England rural life and spirituality.

Today, Whittier is remembered not just as a poet, but as a moral voice in American letters, a writer who used his craft in service of his deeply held beliefs. His commitment to social justice, his celebration of American landscape and culture, and his exploration of spiritual themes continue to resonate with readers and scholars, ensuring his place in the pantheon of American literature.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Everything is free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, your thanks are always welcome but never required.

Thanks!