Since We Must Die

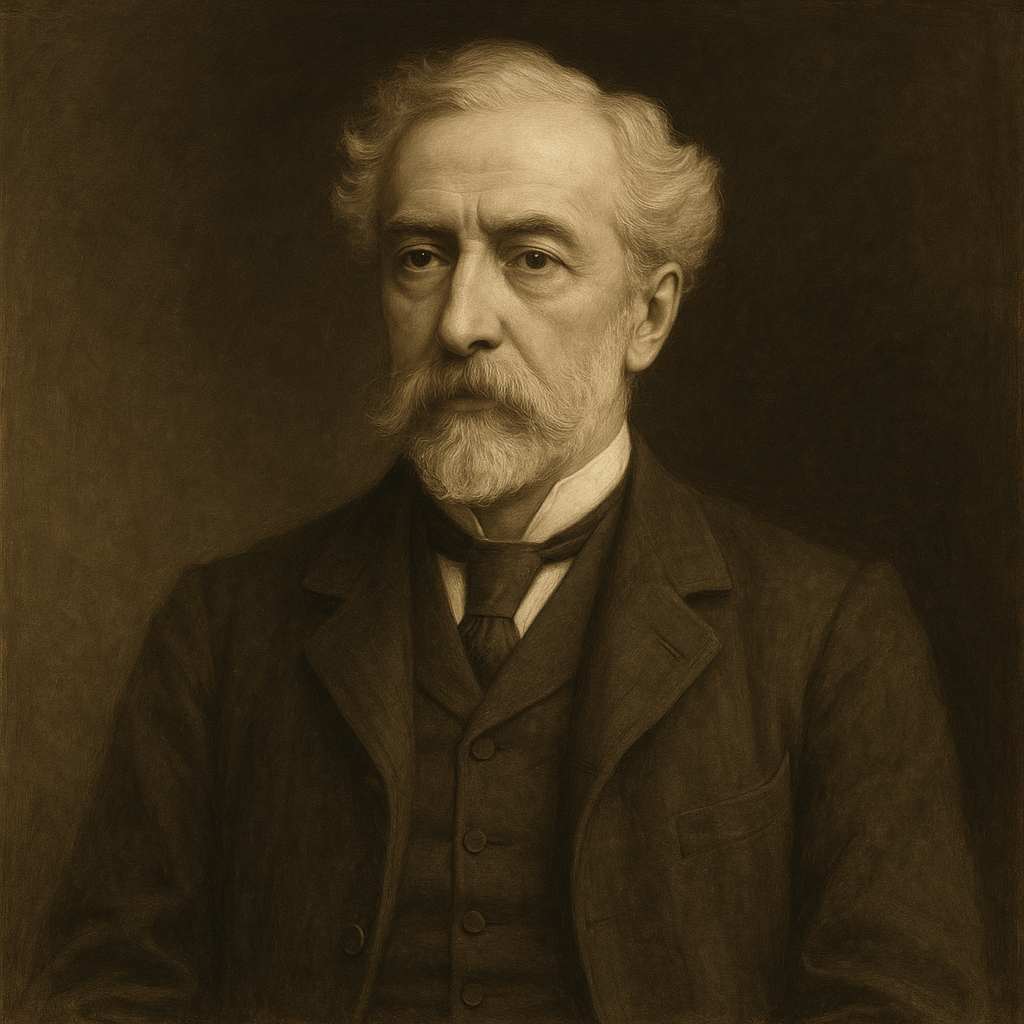

Alfred Austin

1835 to 1913

Though we must die, I would not die

When fields are brown and bleak,

When wild-geese stream across the sky,

And the cart-lodge timbers creak.

For it would be so lone and drear

To sleep beneath the snow,

When children carol Christmas cheer,

And Christmas rafters glow.

Nor would I die, though we must die,

When yeanlings blindly bleat,

When the cuckoo laughs, and lovers sigh,

And O, to live is sweet!

When cowslips come again, and Spring

Is winsome with their breath,

And Life's in love with everything —

With everything but Death.

Let me not die, though we must die,

When bowls are brimmed with cream,

When milch-cows in the meadows lie,

Or wade amid the stream;

When dewy-dimpled roses smile

To see the face of June,

And lad and lass meet at the stile,

Or roam beneath the moon.

Since we must die, then let me die

When flows the harvest ale,

When the reaper lays the sickle by,

And taketh down the flail;

When all we prized, and all we planned,

Is ripe and stored at last,

And Autumn looks across the land,

And ponders on the past:

Then let me die.

Alfred Austin's Since We Must Die

Alfred Austin’s Since We Must Die is a poignant meditation on mortality, temporality, and the human desire to align death with the natural rhythms of life. Through its evocative imagery and structured contemplation of the seasons, the poem explores the tension between life’s fleeting beauty and the inevitability of death. Austin, who served as Britain’s Poet Laureate from 1896 until his death in 1913, often engaged with pastoral and philosophical themes, and this poem is no exception. Here, he crafts a lyrical argument for the ideal moment of death—one that is not arbitrary but harmonized with the cycles of nature and human experience.

This essay will examine Since We Must Die through multiple lenses: its engagement with the carpe diem tradition, its use of seasonal symbolism, its emotional resonance, and its philosophical underpinnings regarding the acceptance of mortality. Additionally, we will situate the poem within the broader context of late Victorian poetry, which frequently grappled with themes of transience and the search for meaning in an increasingly secular age.

The Seasonal Framework and the Ideal Moment of Death

The poem’s structure is built around a series of negations—times when the speaker would not wish to die—before culminating in the affirmative declaration of when death would be most fitting. Each stanza corresponds to a different season or moment in the natural cycle, reinforcing the idea that human life is inextricably linked to the earth’s rhythms.

The first stanza rejects death in winter, a season already associated with barrenness and decay. The imagery of "fields… brown and bleak," the "wild-geese stream[ing] across the sky," and the "cart-lodge timbers creak[ing]" evokes a world winding down into silence. The speaker’s aversion to dying in winter is not merely due to the cold but to the emotional desolation of missing the warmth of human connection: the "children carol[ing] Christmas cheer" and the "Christmas rafters glow[ing]." Death in winter would mean absence during a time of communal joy, intensifying the loneliness of the grave "beneath the snow."

The second stanza shifts to spring, a season traditionally associated with rebirth and vitality. Here, the speaker again resists death, this time because the world is too full of life: "yeanlings blindly bleat," the "cuckoo laughs," and "lovers sigh." The exclamation "O, to live is sweet!" underscores the intoxicating allure of existence when nature is at its most vibrant. The cowslips, a symbol of spring’s return, make "Life… in love with everything— / With everything but Death." The personification of Life as a lover who rejects Death reinforces the poem’s central tension between the desire to live and the inevitability of dying.

The third stanza turns to summer, a time of abundance and sensual pleasure. The speaker rejects death when "bowls are brimmed with cream," when "milch-cows… wade amid the stream," and when "dewy-dimpled roses smile / To see the face of June." The erotic undertones of summer—"lad and lass meet at the stile, / Or roam beneath the moon"—further emphasize life’s richness. To die in summer would be to depart at the height of sensory and emotional fulfillment, a cruel interruption of joy.

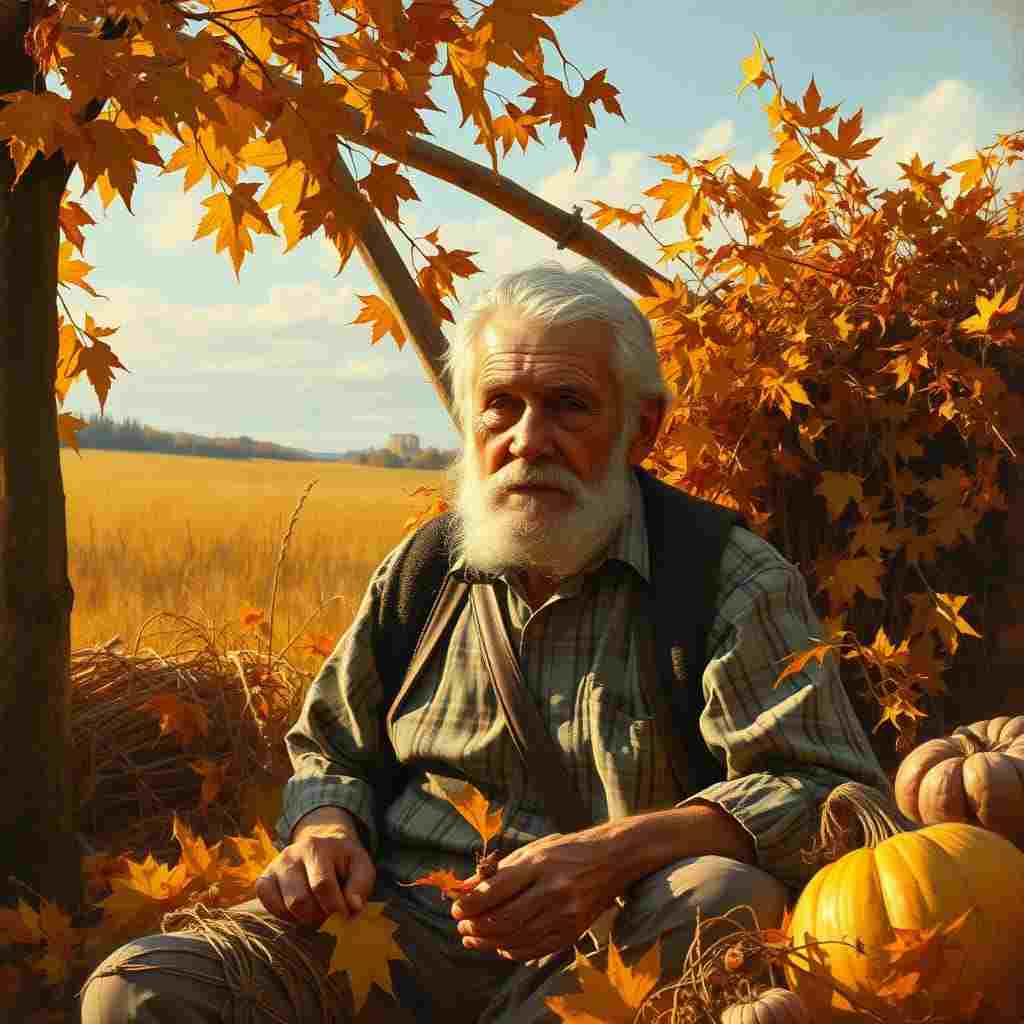

Only in the final stanza does the speaker find an acceptable time for death: autumn, the season of harvest and completion. Here, death is not a disruption but a natural conclusion. The imagery shifts from resistance to acceptance: "When the reaper lays the sickle by, / And taketh down the flail," when all that was "prized, and all we planned, / Is ripe and stored at last." Autumn becomes a metaphor for a life fully lived, where one’s labors have borne fruit, and there is nothing left but reflection. The final lines—"And Autumn looks across the land, / And ponders on the past"—suggest a peaceful, contemplative end, aligning death with the natural closure of the agricultural year.

Literary and Philosophical Contexts

Austin’s poem participates in a long tradition of memento mori poetry, which reminds readers of their mortality, but it does so with a distinctive focus on timing rather than mere inevitability. Unlike the urgent carpe diem poems of the Renaissance (such as Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress), which urge action in the face of death’s certainty, Austin’s poem is more resigned, even serene. It does not seek to escape death but to find the most fitting moment for it.

This perspective aligns with Victorian attitudes toward death, which were shaped by both Romanticism’s reverence for nature and the era’s growing secularism. Without the assured Christian consolation of an afterlife that earlier poets like John Donne might have relied upon ("Death, be not proud"), Austin’s speaker must find meaning within the natural world itself. The poem’s emphasis on seasonal cycles suggests a pantheistic or at least naturalistic view of death—not as an enemy but as part of a larger, inevitable process.

Additionally, the poem’s pastoralism reflects the Victorian nostalgia for rural life amid rapid industrialization. Austin, like many poets of his time, idealizes the countryside as a space of authenticity and harmony, contrasting it with the alienation of urban modernity. The repeated images of agricultural labor ("the reaper," "the flail," "the harvest ale") position death within a pre-industrial framework where human life is still intimately tied to the land.

Emotional Resonance and Universal Appeal

What makes Since We Must Die so affecting is its balance between melancholy and acceptance. The speaker does not rage against death but negotiates with it, seeking a compromise that allows for a dignified exit. This negotiation is deeply human—who has not wished for control over the timing of their own end?

The poem’s emotional power also lies in its sensory richness. Austin does not merely describe seasons abstractly; he fills them with tangible details: the sound of geese migrating, the taste of cream, the scent of roses, the warmth of Christmas gatherings. These details make the plea against death all the more poignant, as they remind us of everything worth living for.

Conclusion: Death as Completion, Not Interruption

In Since We Must Die, Alfred Austin crafts a quiet yet profound argument for the right kind of death—one that comes not as a thief in the night but as a guest arriving at the appropriate hour. By framing mortality within the natural cycle of seasons, he suggests that a good death is one that follows a full life, just as autumn follows summer. The poem’s beauty lies in its acceptance of inevitability while still cherishing the transient joys of existence.

In an age where death was increasingly medicalized and removed from daily life, Austin’s poem reconnects it to the rhythms of nature and human labor. It is a reminder that, though we must die, we may still hope for an ending that feels like completion rather than interruption. In this way, the poem transcends its Victorian context, speaking to any reader who has ever wished for a death that is not untimely but timely—a final, harmonious note in the symphony of life.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!