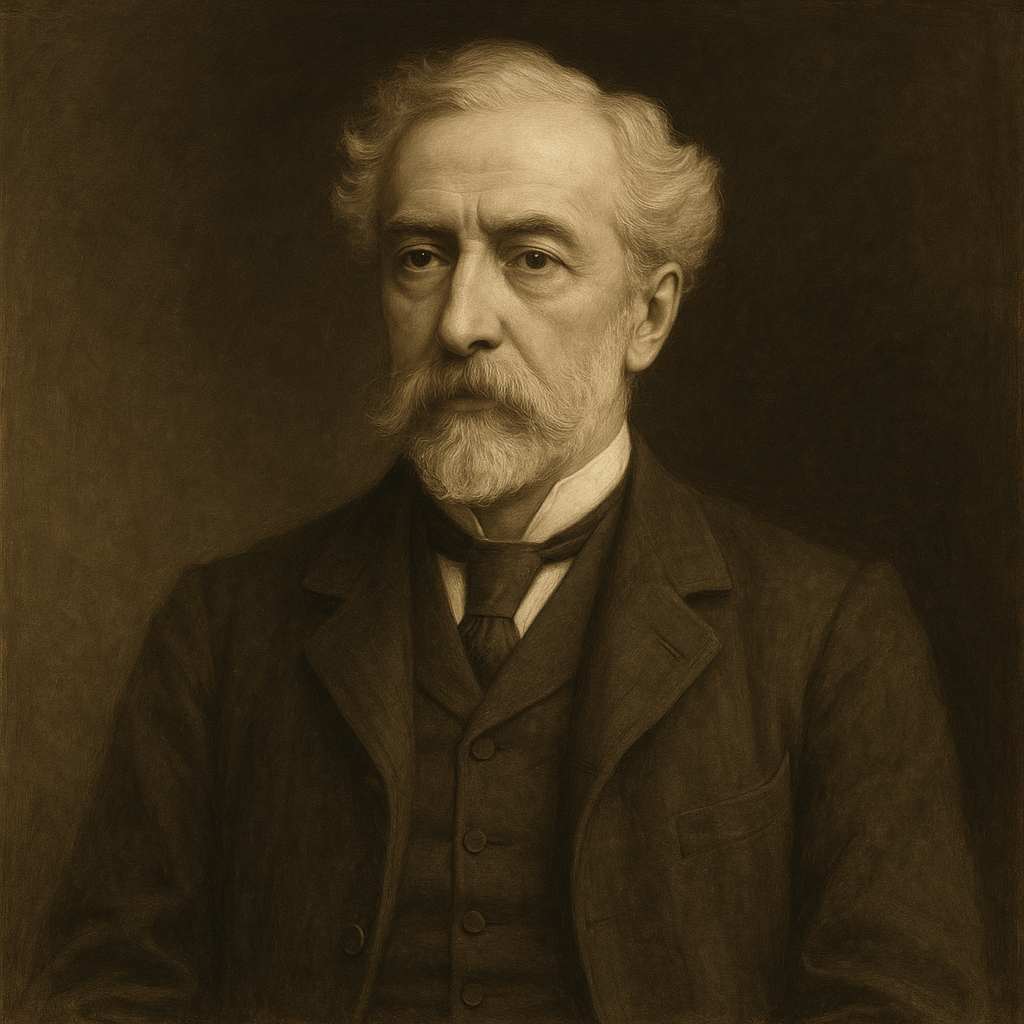

9 Poems by Alfred Austin

1835 - 1913

Alfred Austin Biography

Alfred Austin, a poet whose reputation waxed and waned through the late Victorian era, is remembered today less for the sheer brilliance of his poetry than for the peculiar nature of his appointment as England's Poet Laureate in 1896. Austin’s life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the literary and political landscape of Victorian Britain, a time when poetry was both a public platform and an art of deeply personal expression. Often maligned for his seemingly conventional verse and eclipsed by the legacy of his predecessor Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Austin's career reflects the challenges and transformations that British poetry encountered as it moved toward the 20th century.

Born on May 30, 1835, in Headingley, a suburb of Leeds, Austin was the son of Joseph Austin, a prosperous Roman Catholic merchant, and his wife Mary, of a similarly devout background. His upbringing in a Catholic family in an England where Catholicism was still regarded with suspicion imparted a sense of cultural otherness that influenced his views and, arguably, his poetry. Austin was educated at Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit institution with a rigorous curriculum in the classics, before he matriculated at the University of London, where he read law. In 1857, Austin was called to the Bar, but his legal career proved unsatisfying and he quickly turned his attention to writing, his true passion.

Austin’s early literary ambitions coincided with a period in British letters that celebrated the Romantic legacy while at the same time was marked by the emergence of Realism in literature. In his early twenties, Austin published several novels and attempted to forge a literary reputation as a writer capable of exploring social issues with wit and moral clarity. His initial novels, including Five Years of It (1858) and The Human Tragedy (1862), met with a lukewarm reception. These works reveal a young man searching for his voice, one caught between his Romantic inclinations and a more Victorian, socially engaged approach to art.

Turning increasingly toward poetry, Austin found himself influenced by the moral earnestness of Tennyson as well as the pastoral themes that he would later make his own hallmark. Austin's poetry from this period, however, was not particularly well received by critics, who found it derivative and lacking the fervent originality that characterized other poets of his day, such as Robert Browning or Gerard Manley Hopkins. Nevertheless, he continued to write, driven by an unwavering belief in poetry as a medium for moral and social improvement.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Austin's interest in journalism flourished, and he became a significant contributor to several conservative periodicals. This period of his life saw him shift focus from Romantic poetry to political commentary, eventually securing a position as a leading voice in conservative political journalism. As an editor and contributor for the Standard, he wrote extensively on issues of foreign policy, social reform, and British identity. This engagement with the political sphere not only connected him to key figures in British politics but also exposed him to the sometimes harsh realities of public discourse.

Austin’s increasingly conservative views were reinforced by his association with influential figures within the Conservative Party, particularly Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, who held Austin’s journalistic work in high regard. Austin’s friendships with powerful political figures helped to cement his reputation as a spokesman for Conservative ideals. However, this entanglement with political circles would later lead to accusations that his literary career was, to some extent, propelled by patronage rather than poetic prowess—a perception that dogged him even as he achieved his most significant appointment.

When Alfred, Lord Tennyson died in 1892, the position of Poet Laureate—a highly prestigious appointment with a lineage that included literary giants such as William Wordsworth—was left vacant. It took four years before Queen Victoria’s government would settle on a successor. During this interim, several prominent poets, including William Morris, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and Rudyard Kipling, were considered but ultimately declined for various reasons. When Austin was chosen in 1896, the decision met with widespread surprise and some disappointment. Critics argued that Austin lacked the innovative power or emotional depth of his contemporaries, especially in comparison to Tennyson. His appointment, rumored to have been the result of his political connections rather than literary merit, cast a shadow over his reputation that he never fully dispelled.

Austin took his role seriously, however, and he fulfilled his official duties with a sense of propriety, frequently penning poems to commemorate public events and royal occasions. Yet these “official” poems, often stiffly conventional in their style and themes, did little to elevate his standing among critics or the public. One example is his ode on the illness of the Prince of Wales, written with the earnestness he no doubt felt but derided for its sentimental tone and lack of linguistic vigor. His 1897 work “The Splendid Failure,” a poem commemorating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, attempted to embody the grandeur of the British Empire but was viewed as lacking the lyrical sophistication that such an occasion might have warranted.

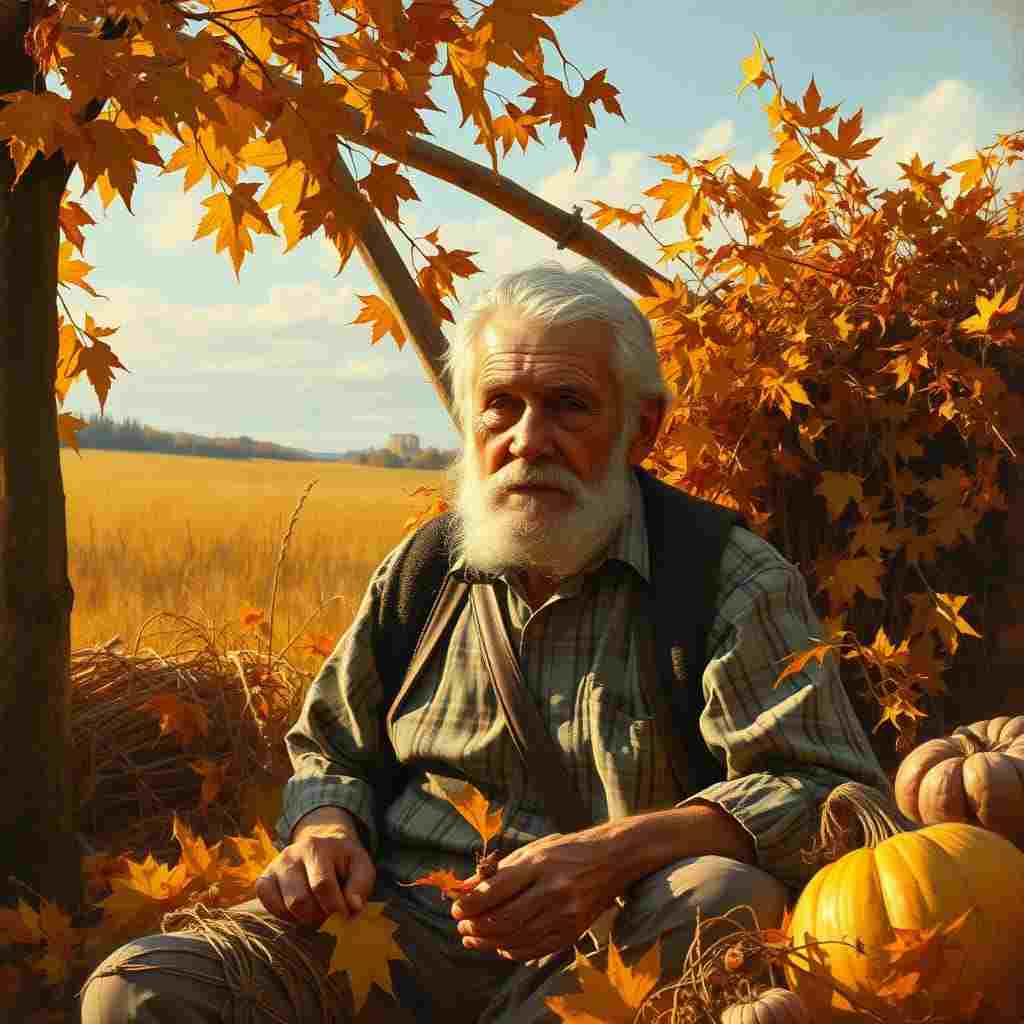

Outside his laureate duties, Austin’s true passion lay in nature poetry, and it is in his pastoral works that one finds his most sincere and personal expressions. Works such as The Garden That I Love (1894) and Lamia’s Winter-Quarters (1907) reflect Austin’s deep appreciation for the English countryside, celebrating the simple, undisturbed beauty of rural landscapes. Influenced by the tradition of Romantic nature poetry yet tempered by the Victorian emphasis on restraint and moral reflection, Austin’s nature poems often reveal a certain nostalgia, a yearning for an unspoiled England. His descriptions of flora and fauna, gardens and seasons, all speak to a heartfelt reverence for the natural world. These poems, while never achieving critical acclaim, have a gentleness and authenticity that stand apart from the more bombastic tone of his laureate poems.

Austin’s pastoral work was not universally derided, and indeed he had some defenders who appreciated his sentimentality and his connection to traditional poetic forms. His verse, characterized by its careful construction and accessible language, appealed to readers who valued the continuity of English literary traditions. In an era increasingly marked by the complexities of Modernism, Austin’s poetry, with its straightforward diction and conventional forms, felt reassuringly familiar, if somewhat outdated.

It is also notable that Austin, despite his conservatism, was not untouched by the currents of poetic innovation around him. His essays and reviews indicate a careful, albeit sometimes critical, attention to the changing literary landscape. He famously wrote unfavorably about Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d'Urbervilles, disliking its portrayal of social tragedy and its challenge to Victorian moral sensibilities. Austin’s resistance to Hardy and the Modernists reveals much about his literary outlook; he saw poetry and literature as vehicles for promoting moral order, rather than interrogating or dismantling it. This conservatism was both his strength and his limitation: it lent him a clear and consistent voice, yet it isolated him from the broader movements that would come to define 20th-century literature.

As the years wore on, Austin’s work fell increasingly out of fashion. His laureateship ended with his death in 1913, and the position passed to Robert Bridges, a poet whose own style also leaned toward classical forms but with a subtler innovation that critics appreciated. By the time of his death, Austin’s poetry was largely forgotten, overshadowed by the emergent voices of Modernism and the rapid changes in British society that left little room for his brand of moral and pastoral verse.

In retrospect, Alfred Austin’s legacy is a complex one. He was a poet whose talents perhaps did not match the expectations or demands of his official role, yet he was, in his own way, dedicated to his art. His nature poems, with their delicate evocations of the English landscape, remain worth reading as examples of a poetic sensibility in dialogue with both the Romantic past and a rapidly industrializing society. His tenure as Poet Laureate, though controversial, illustrates the intricate ties between poetry, politics, and national identity in Victorian Britain.

While Austin may never be held in the same regard as his peers, his life offers a unique perspective on the struggles and aspirations of a poet caught between worlds—between Romanticism and Modernism, between genuine passion for nature and a public role demanding lofty, patriotic verse. In his loyalty to his vision of poetry, however humble, Alfred Austin reminds us of the quiet but enduring beauty of tradition, even in an era on the brink of transformation.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Username Information

No username is open

Unique usernames are free to use, but donations are always appreciated.

Quick Links

© 2024-2025 R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody).

All music on this site by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Attribution Requirement:

When using this music, you must give appropriate credit by including the following statement (or equivalent) wherever the music is used or credited:

"Music by R.I.Chalmers (V2Melody) – https://v2melody.com"

Support My Work:

If you enjoy this music and would like to support future creations, donations are always welcome but never required.

Donate