Love's Unity

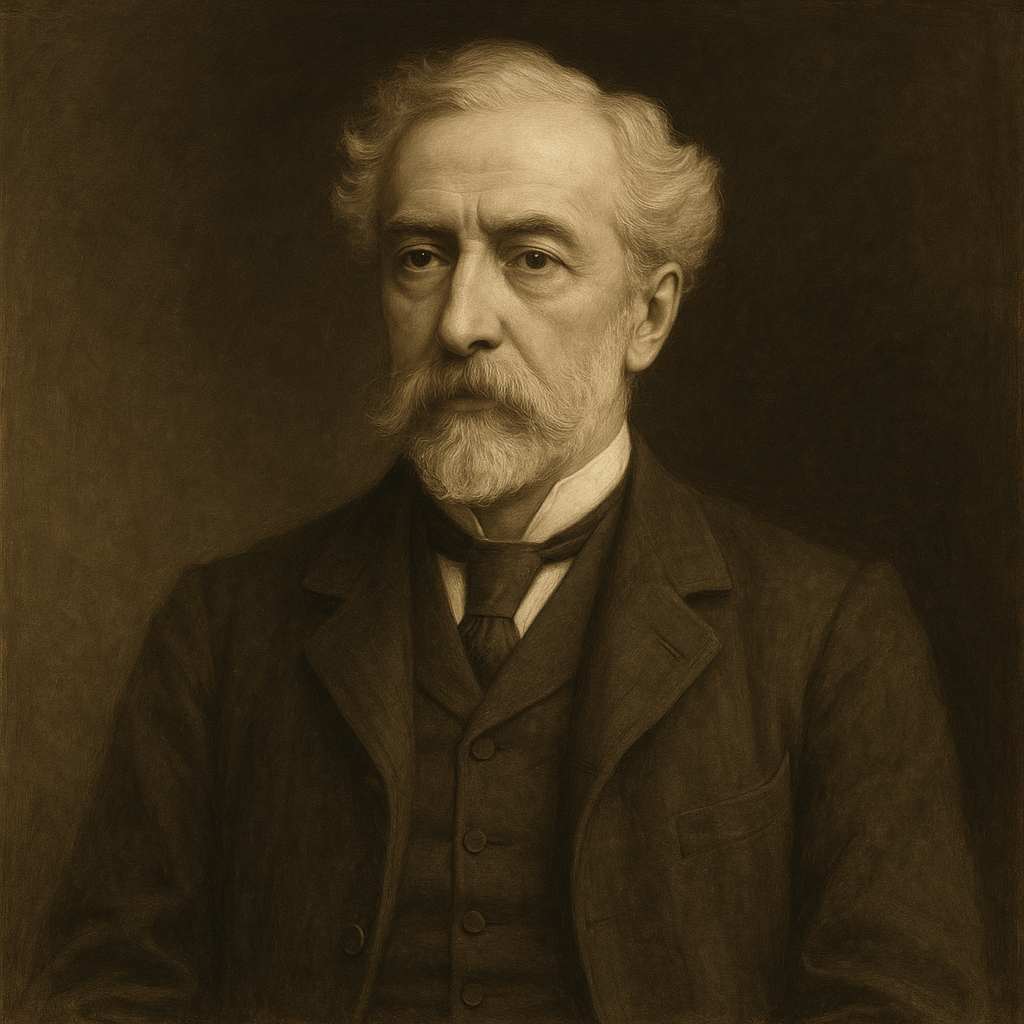

Alfred Austin

1835 to 1913

Want to track your favorites? Reopen or create a unique username. No personal details are required!

How can I tell thee when I love thee best?

In rapture or repose? how shall I say?

I only know I love thee every way,

Plumed for love's flight, or folded in love's nest.

See, what is day but night bedewed with rest?

And what the night except the tired-out day?

And 'tis love's difference, not love's decay,

If now I dawn, now fade, upon thy breast.

Self-torturing sweet! Is't not the self-same sun

Wanes in the west that flameth in the east,

His fervour nowise altered nor decreased?

So rounds my love, returning where begun,

And still beginning, never most nor least,

But fixedly various, all love's parts in one.

Alfred Austin's Love's Unity

Alfred Austin’s Love’s Unity is a sonnet that explores the paradoxical nature of love—its constancy amidst change, its unity within diversity, and its ability to encompass both passion and tranquility. Written in the late 19th century, during Austin’s tenure as British Poet Laureate (1896–1913), the poem reflects Victorian sensibilities regarding romantic idealism while also engaging with metaphysical questions about the nature of love. Through its intricate imagery, cyclical structure, and philosophical musings, the poem transcends mere personal expression, offering a meditation on love as an eternal, all-encompassing force.

Historical and Biographical Context

Alfred Austin (1835–1913) was a conservative poet whose work often celebrated nature, patriotism, and traditional values. His appointment as Poet Laureate was met with mixed reactions, as some critics found his poetry lacking in depth compared to his predecessors, Tennyson and Wordsworth. However, Love’s Unity demonstrates a lyrical and intellectual sophistication that challenges such dismissals. Written in the latter half of the 19th century, the poem emerges from a cultural moment where Romanticism’s emotional intensity had given way to Victorian introspection and formalism.

Austin’s personal life may also inform the poem’s tone. Though he never married, his writings frequently idealize love, suggesting a longing for an enduring, almost spiritual connection. The poem’s philosophical approach to love—viewing it as both mutable and unchanging—aligns with Victorian ideals that sought to reconcile passion with stability, a tension evident in the works of contemporaries like Robert Browning and Christina Rossetti.

Thematic Analysis: Love as Paradox and Unity

The central theme of Love’s Unity is the reconciliation of opposites within love. The speaker questions how to define the "best" moment of love—whether in "rapture or repose"—only to conclude that love transcends such distinctions. This paradox is reinforced through natural imagery: day and night, the rising and setting sun, and the cyclical movement of celestial bodies.

The poem’s opening lines establish this tension:

How can I tell thee when I love thee best?

In rapture or repose? how shall I say?

Here, Austin juxtaposes ecstasy ("rapture") with calm ("repose"), suggesting that love is not confined to a single emotional state. The speaker’s inability to choose between these extremes implies that love’s essence lies in its capacity to hold contradictions in balance.

This idea is further developed through the metaphor of day and night:

See, what is day but night bedewed with rest?

And what the night except the tired-out day?

These lines suggest that day and night are not opposites but transformations of the same phenomenon. Similarly, love’s apparent fluctuations—its moments of intensity and quietude—do not signify inconsistency but rather different manifestations of the same enduring emotion.

Literary Devices and Imagery

Austin employs a range of poetic techniques to convey love’s dual nature. The sonnet form itself, with its structured yet flexible framework, mirrors the poem’s theme of unity within variation. The volta, or turn, occurs subtly, shifting from questioning to affirmation:

And 'tis love's difference, not love's decay,

If now I dawn, now fade, upon thy breast.

Here, the speaker reassures the beloved that love’s changing expressions do not indicate its diminishment. The imagery of "dawn" and "fade" reinforces the cyclical motif, suggesting that love, like the sun, undergoes natural phases without losing its essence.

The most striking metaphor in the poem is that of the sun:

Is't not the self-same sun

Wanes in the west that flameth in the east,

His fervour nowise altered nor decreased?

This celestial imagery elevates love to a cosmic principle, immutable despite its apparent movements. The sun’s constancy, despite its changing positions, becomes a symbol for love’s enduring power. The phrase "fixedly various" in the final line encapsulates this idea perfectly—love is both unchanging and dynamic, a paradox that defines its unity.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Love as a Cosmic Force

The poem’s philosophical resonance extends beyond personal emotion, aligning with Neoplatonic and Romantic conceptions of love as a universal force. The idea that love "returns where begun" echoes the ancient notion of eternal recurrence, found in Stoicism and later in Nietzsche’s philosophy. Austin’s depiction of love as cyclical and self-renewing suggests an almost metaphysical permanence, transcending individual experience.

Furthermore, the closing lines—

So rounds my love, returning where begun,

And still beginning, never most nor least,

But fixedly various, all love's parts in one.

—evoke the imagery of the ouroboros, the serpent eating its own tail, a symbol of infinity and eternal return. Love, in this view, is not linear but circular, perpetually regenerating itself.

Comparative Readings

Austin’s treatment of love invites comparison with other Victorian poets. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese similarly explores love’s constancy, yet where Browning’s sonnets are intensely personal, Austin’s poem leans toward abstraction, framing love as an almost impersonal force.

Another fruitful comparison is with John Donne’s The Sun Rising, which also employs solar imagery to assert love’s supremacy over time and space. However, while Donne’s poem is defiant and dramatic, Austin’s is meditative and serene, reflecting differing historical attitudes toward love’s relationship with the cosmos.

Emotional Impact and Universality

Despite its philosophical depth, Love’s Unity remains deeply emotive. The speaker’s tender address ("How can I tell thee") grounds the poem in intimacy, while the cosmic imagery universalizes the emotion, allowing readers to see their own experiences reflected in its lines. The poem’s beauty lies in its ability to articulate a truth many lovers feel but struggle to express—that love is not diminished by its variations but enriched by them.

Conclusion

Alfred Austin’s Love’s Unity is a masterful exploration of love’s paradoxical nature—its ability to be both constant and ever-changing, passionate and tranquil, personal and universal. Through rich imagery, cyclical structure, and philosophical depth, the poem transcends its Victorian context, offering a timeless meditation on the enduring power of love. While Austin may not be as celebrated as some of his contemporaries, this sonnet stands as a testament to his poetic skill and his capacity to capture the profound complexities of human emotion. In an age where love is often reduced to fleeting passion or sentimental cliché, Love’s Unity reminds us that true love is neither static nor inconsistent but "fixedly various"—an eternal dance of unity within diversity.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!