Especially when the October wind

Dylan Thomas

1914 to 1953

Especially when the October wind

With frosty fingers punishes my hair,

Caught by the crabbing sun I walk on fire

And cast a shadow crab upon the land,

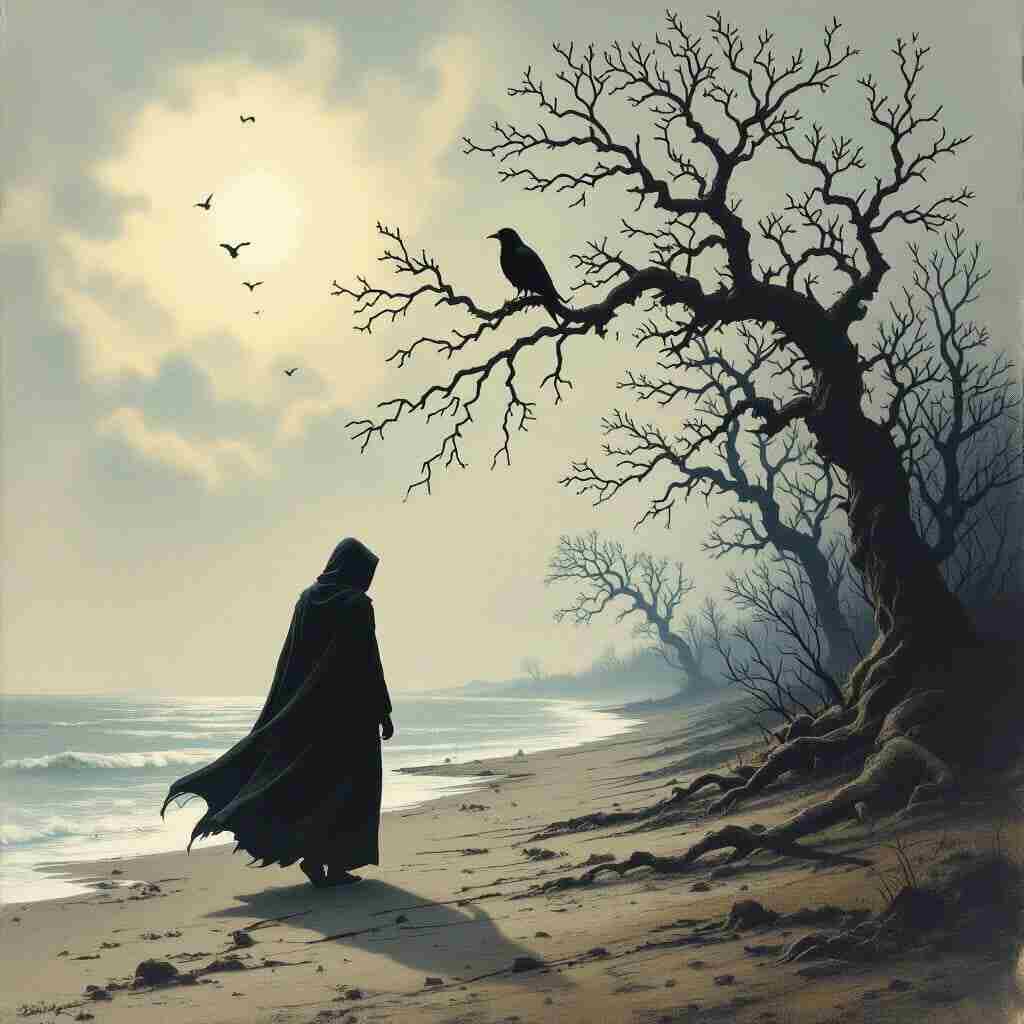

By the sea’s side, hearing the noise of birds,

Hearing the raven cough in winter sticks,

My busy heart who shudders as she talks

Sheds the syllabic blood and drains her words.

Shut, too, in a tower of words, I mark

On the horizon walking like the trees

The wordy shapes of women, and the rows

Of the star-gestured children in the park.

Some let me make you of the vowelled beeches,

Some of the oaken voices, from the roots

Of many a thorny shire tell you notes,

Some let me make you of the water’s speeches.

Behind a pot of ferns the wagging clock

Tells me the hour’s word, the neural meaning

Flies on the shafted disk, declaims the morning

And tells the windy weather in the cock.

Some let me make you of the meadow’s signs;

The signal grass that tells me all I know

Breaks with the wormy winter through the eye.

Some let me tell you of the raven’s sins.

Especially when the October wind

(Some let me make you of autumnal spells,

The spider-tongued, and the loud hill of Wales)

With fists of turnips punishes the land,

Some let me make you of the heartless words.

The heart is drained that, spelling in the scurry

Of chemic blood, warned of the coming fury.

By the sea’s side hear the dark-vowelled birds.

Dylan Thomas's Especially when the October wind

Dylan Thomas’s “Especially when the October wind” is a richly textured poem that exemplifies his signature linguistic density, sonic intensity, and preoccupation with the interplay between nature, language, and human consciousness. Written in the mid-20th century, the poem reflects Thomas’s broader poetic concerns—mortality, the cyclical violence of nature, and the poet’s struggle to articulate experience through words. This essay will explore the poem’s historical and cultural context, its intricate use of literary devices, its central themes, and its emotional resonance, while also considering comparative and philosophical perspectives where relevant.

Historical and Cultural Context

Dylan Thomas (1914–1953) wrote during a period of immense upheaval—between the two World Wars and in the shadow of modernist experimentation. His work, however, resists easy classification within modernist or post-war movements. Unlike T.S. Eliot’s fragmented urban landscapes or W.H. Auden’s political urgency, Thomas’s poetry is deeply rooted in the Welsh landscape, myth, and a Romantic sensibility that privileges sensory and emotional intensity.

The poem’s fixation on October—a month of decay and transition—aligns with Thomas’s broader fascination with liminal states. October is neither fully autumn nor yet winter; it is a time of both beauty and brutality, as seen in the “frosty fingers” that “punish” the speaker’s hair. This duality reflects post-war anxieties, where the natural world’s cycles mirror human vulnerability. The Welsh setting, hinted at in “the loud hill of Wales,” grounds the poem in a specific cultural and geographical context, where folklore and natural forces shape perception.

Thomas’s work also engages with the legacy of Romanticism, particularly the tradition of poets like Keats and Wordsworth, who saw nature as both muse and antagonist. However, Thomas’s approach is more visceral and less idealized—nature here is not just sublime but actively violent, “punishing” the land with “fists of turnips.”

Literary Devices and Linguistic Innovation

Thomas’s poetry is renowned for its linguistic exuberance, and this poem is no exception. He employs a range of literary devices to create a dense, almost incantatory effect:

1. Imagery and Synesthesia

The poem is saturated with vivid, often unsettling imagery that blends the senses. The “frosty fingers” of the wind evoke tactile coldness, while the “crabbing sun” suggests both the crustacean’s scuttling motion and the sun’s harsh, pinching light. The synesthetic merging of senses—where words have tactile, visual, and auditory dimensions—creates a disorienting yet immersive experience.

2. Personification

Nature is repeatedly anthropomorphized, often in menacing ways. The wind “punishes,” the raven “coughs,” and the clock “wags” like a scolding finger. These personifications blur the boundary between the human and natural worlds, suggesting a universe where all elements are animate and interactive.

3. Paradox and Oxymoron

Thomas frequently employs paradoxical constructions to heighten tension. The speaker walks “on fire” yet casts a “shadow crab”—an image that merges burning intensity with the cold, creeping motion of a crustacean. The “neural meaning” that “flies on the shafted disk” combines biological and mechanical imagery, reflecting the poem’s preoccupation with the intersection of organic and linguistic structures.

4. Symbolism

-

The Raven: Traditionally a symbol of death and prophecy (echoing Poe and Celtic myth), the raven here “coughs in winter sticks,” suggesting illness and decay.

-

The Tower of Words: Represents the poet’s self-imposed isolation within language, a motif seen in Yeats’s The Tower and Rilke’s Duino Elegies.

-

The “Signal Grass”: A natural oracle, the grass “tells me all I know,” positioning nature as both a source of wisdom and a reminder of mortality (“breaks with the wormy winter through the eye”).

5. Sound and Rhythm

Though this analysis avoids discussing rhyme, Thomas’s use of alliteration, assonance, and consonance creates a musical, almost hypnotic quality. Phrases like “shudders as she talks / Sheds the syllabic blood” and “the windy weather in the cock” demonstrate his mastery of sonic texture, where meaning is reinforced by sound.

Themes

1. The Violence of Nature and Time

October’s wind is not gentle but punitive, embodying nature’s capacity for cruelty. The “fists of turnips” suggest both agricultural labor and nature’s blunt force. Time, too, is relentless—the “wagging clock” dictates the hour, and the “chemic blood” warns of “the coming fury,” possibly alluding to both personal mortality and apocalyptic dread (relevant in the nuclear age).

2. The Poet’s Struggle with Language

The speaker is “Shut… in a tower of words,” a metaphor for the poet’s entrapment within his own craft. Language is both a refuge and a prison. The “syllabic blood” suggests that words are extracted painfully, like a vital fluid. This aligns with Thomas’s broader view of poetry as a bodily, almost sacrificial act.

3. Communion and Isolation

The repeated plea—“Some let me make you of…”—implies a desire to transmute experience into shared meaning, whether through “vowelled beeches” or “water’s speeches.” Yet the speaker remains isolated, hearing only “the dark-vowelled birds” by the sea. This tension between connection and solitude is central to Thomas’s work.

4. Myth and Transformation

The poem’s imagery draws on Celtic and biblical motifs (ravens, towers, sacrificial blood). The speaker seeks to “make you” (the reader or an unnamed listener) out of natural elements, suggesting a quasi-magical act of creation. This aligns with the Romantic idea of the poet as a visionary, but Thomas’s vision is darker, more fraught.

Emotional Impact and Philosophical Undercurrents

The poem’s emotional power lies in its fusion of beauty and menace. The October wind is both exhilarating and oppressive, much like the creative process itself. The speaker’s “busy heart” that “shudders as she talks” captures the visceral anxiety of artistic expression—words are not just spoken but bled.

Philosophically, the poem engages with existential questions: How does one articulate the ineffable? Can language ever fully capture experience? Thomas’s answer seems ambivalent. Words are both a “tower” (a structure of meaning) and a prison. The final image of “dark-vowelled birds” suggests that even nature speaks in cryptic, ominous tones.

Comparatively, Thomas’s work resonates with Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, where poetry is a bridge between life and death, and with Hopkins’s “terrible sonnets,” where divine and natural forces collide. Yet Thomas’s voice is distinct in its lush, almost grotesque physicality.

Conclusion

“Especially when the October wind” is a masterful exploration of nature’s brutality, the poet’s agonized creativity, and the limits of language. Its historical context—post-war, Welsh, and Romantic-inflected—shapes its themes, while its linguistic virtuosity ensures its enduring power. Thomas does not merely describe October’s wind; he makes us feel it, in all its punishing, exhilarating force. The poem stands as a testament to poetry’s capacity to distill the raw essence of experience, even when that essence is fraught with terror and beauty.

This text was generated by AI and is for reference only. Learn more

Want to join the discussion? Reopen or create a unique username to comment. No personal details required!

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!